Advertisement

Trump Administration Decision Puts Tribal School In Limbo

As legal wrangling continues over the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe's reservation land, tribal leaders voice concerns that a major point of pride, its school, could be threatened.

Last September, the U.S. Department of the Interior ruled that it could no longer hold land in trust for the tribe. Having land in held in trust by the federal government essentially gives the tribe autonomy to make decisions over how to tax, develop and manage the area.

While it’s unclear what exactly the next steps are for the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe, there’s a lot at stake if the tribe loses that special status for its 321 acres of land.

One of biggest possible changes, which most often makes the news and is top of mind for many nearby residents, is a proposal for a $1 billion casino in Taunton. But there’s even more in limbo.

“If the trust were removed today then tomorrow we wouldn’t be operating a school,” said Jessie Little Doe Baird, the tribe’s vice chairwoman.

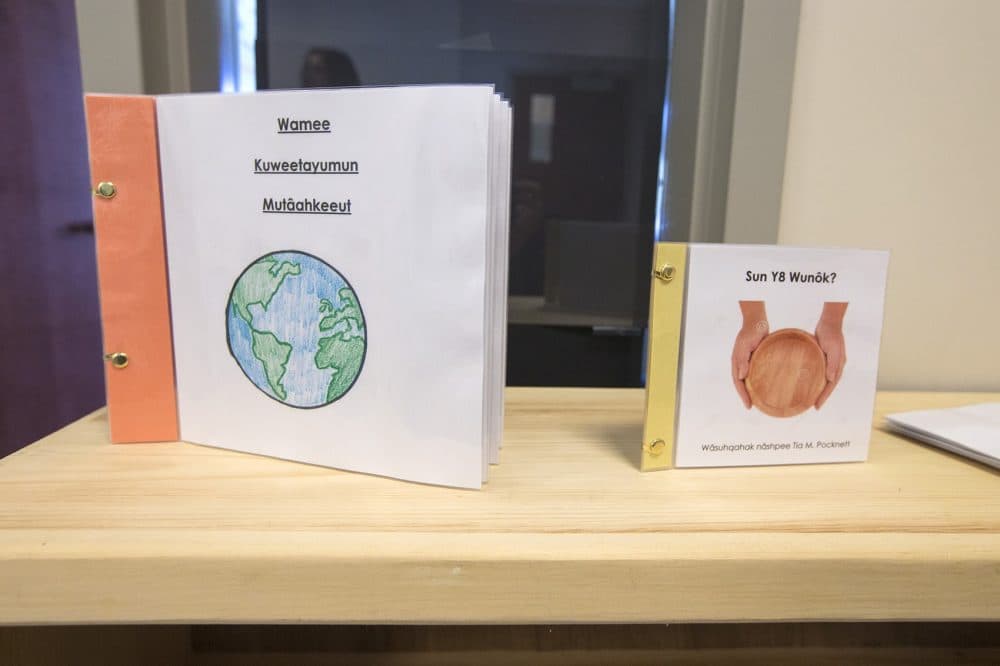

That language immersion school, Mukayuhsak Weekuw, is one of several key establishments that the tribe has built on the sovereign reservation land since it was taken into trust in 2015, including: its own police department, a natural resources agency and the beginnings of an affordable housing development.

All of those are at risk, if the Trump administration takes the land out of trust. Land has not been taken out of trust since the Termination Era of the 1940s through 1960s, a time when Congress tried to end tribal independence by taking away federal protections. The Mashpee Wampanoag tribe has sued the Interior Department to reverse its 2018 decision.

If the tribe loses that federally protected status, there are unique challenges for the school.

Take the physical building: The preschool, kindergarten and 1st grade classrooms are all housed, rent free, in the Mashpee Wampanoag Government Center. The 46,000 square foot building is not subject to state and local property taxes.

Advertisement

But if the land became private again, the tribe would have to start paying those taxes, and could possibly be on the hook for back taxes. And if that happened, tribal officials said, running the building would become a lot more expensive and they might have to charge rent to the nonprofit school.

Then, the rules would change.

“The school is on a reservation so that means it’s permitted by tribal law. Not by state law or local law,” said Baird. “So should the jurisdiction be moved then the facility is no longer in compliance.”

That would mean the tribe would basically have to create a new private school, which adheres to state regulations. They would have to get approval from the Mashpee Public Schools committee. The tribe would also have to create systems for gathering and reporting student health, attendance and other data.

While Baird said it would be possible to make those changes, the tribe might have to close the school temporarily as it goes through the legal transition.

“I don’t think it’s a matter of pride,” Baird said of running the school on the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe's reservation. “I think it’s a matter of necessity and it’s an exercise in sovereignty.”

Regardless of the paperwork and increased costs, the biggest blow to the tribe might be that potential loss of autonomy.

“There really isn’t a governing body or a regulatory body within the state that has an understanding of Wampanoag language and culture,” said Jennifer Weston, the project director of Mukayuhsak Weekuw. “So we really feel it’s important to continue to operate as an independent tribal entity.”

The school currently runs under a Montessori framework that centers every lesson — whether it’s math, science or social studies — around the Wampanoag language and culture.

“We are largely focused on imparting cultural values, and knowledge important to the tribal philosophy,” said Weston. “Our children learn every day how their ancestors have lived here in Mashpee, on these lands, for many thousands of years.”

Weston added the Wampanoag language itself emerged from the land and its traditional uses. And a person’s sense of self is intertwined with the land. The tribe's language fluency coach, Nitaha Hicks Greendeer, explained the phrase "my land" translates to the word “nutahkeem" in Wampanoag. But she said the Wampanoag word holds more of a meaning that the land is part of your body.

“So there’s no separation. Without the land we’re not fully ourselves,” she said. Greendeer’s three kids go to Mukayuhsak Weekuw, and she’s been impressed with how much they know about their culture at such a young age.

Tribal leaders are still optimistic that they will be able to keep their land, whether through a judge’s order or through a bill filed in Congress last week. The legislation — co-sponsored by Rep. Bill Keating and several key Republicans including Reps. Tom McClintock and Doug LaMalfa of California and Don Young of Alaska — would effectively overrule the 2018 Interior Department decision and protect the land's federal trust status.

“We think it's a misguided piece of legislation and hopefully will be found unconstitutional,” said David Tennant, an attorney representing 25 citizens in Taunton who filed the original legal challenge against the tribe’s trust land.

Rep. Keating said he believes his bill is constitutional and bipartisan.

“There is a feeling that this type of action can have an effect on other tribes,” he said. Keating expects the legislation will pass the House in the coming weeks.