Advertisement

At Tufts, Harry Dodge’s 'Works Of Love' Is A Valentine To Both The Alien And The Earthly

Like everything else in the world, human beings are constantly evolving, shifting and transmuting, both on the level of consciousness and the level of form. When it comes to form, we seem to have sprouted strange rectangular devices in the last decade or so. They attach to our hands, can play video games and place calls to loved ones. Our new appendages connect us to people we have never met who are aware of our every movement, while distancing us from people we once knew well, who no longer hear our voices but deduce that we’re alive thanks to text messages. On some level, we have become the digital and the digital has become us.

With this in mind, it’s easy to enter the universe of artist Harry Dodge, who is fascinated with the increasingly narrow passage between what it means to be human and what it means to be machine. In our Siri and Alexa-ized world, a world of artificial intelligence, self-driving cars, automated customer service representatives, robotic nurses and children who think and behave differently thanks to hours of daily screen time, perhaps we’ve even entered a post-human phase.

It would be funny if it weren’t also kind of scary.

Dodge, however, summons more joy than fear in "Harry Dodge: Works of Love," on view at Tufts' Aidekman Arts Center in Medford beginning Jan. 17. An LA-based sculptor, performer, video artist and writer, Dodge offers a selection of recent sculptural assemblages, drawings and videos, all of which manage to blend industrial elements with oddly human characteristics. And so, we have aluminum piping, speed-rail joints, rocket-ship vents and glossy automotive lacquer (particularly appropriate for an artist working in LA) combined with droopy socks that might stand in for very human phalluses, noses, breasts or some other non-machine appendage. Tilted paint buckets with messy black goo hearken to the mess of a manufacturing process, or perhaps to more corporeal messes of the human kind. These works are both human and widget-like, male and female, sexual and asexual, messy and precise, humorous and deadly serious. It’s the inbetweeness of it all, the undefinable quality, that makes it all so interesting. The work, to use Dodge’s term, is “ecstatically contaminated.”

“Ecstatic contamination is a term I use to combine a couple of related ideas,” he says. “It refers to a kind inter-relationality that I'm super interested in. The way we're not totally separate, the way we're permeated by everything else, even those things we would hope to be uncontaminated by. I want to introduce the idea that it's possible to re-evaluate ourselves as joyfully imperfect; and in this way become more compassionate, and find less and less taste for staunchness, polarization based on a sense of self-righteous purity. I don't want to seek comfort in purity; right on the other side of purity, as you know, is fascism.”

Certainly, there’s nothing pure about Dodge’s work. Although some of his pieces may feel as if they have come from a forgotten sketchbook of modernist sculptors Anthony Caro or David Smith — Dodge pushes beyond cool formality into something much more hot. The hotness comes in his work’s visceral quality that can easily recall body parts if not bodily functions.

Advertisement

In “Pure S--- Hotdog Cake,” tiers of plywood drip with hardened urethane resin in bright magenta, orange, yellow and green. An aluminum pipe armature supports a form that looks like layers of a wedding cake. The structure's got two plexiglass wings reminiscent of a space satellite or, more mundanely, the head of a Swiffer mop. At the top of this odd wood-and-metal cake confection sits a can of yellow paint, and above that something that looks an awful lot like a hot dog. On one side of the structure, a pipe proffers a photograph of the structure itself — a sort of tech-age selfie. The whole effect is weird and whimsical, humorous and plaintive, carnival-like with all the fluorescent color, but also industrial and mechanical with all the pipes and plexiglass. The assemblage strikes a balance between the warm and fuzzy world of the human, a world of festive wedding cakes and street-fair hot dogs and that of the industrial — the world of antennas, satellites, aluminum pipes, stainless steel and hardware.

“Most organisms, most styles of communication or expression have both analog and digital elements,” reflects Dodge. “There are definitely popularized aesthetics of futurism and industrialism, I get that. But the fact is, I'm interested in breaking down a sense of total rupture as we enter the future. In other words, perhaps one might think of the show as a provocation. As a viewer, I'm asked to consider many things; not the least of which is the idea that art practice might be considered to be generating love; that these apparently-stationary sculptures are being proposed as fluid forms; and common industrial items might be intended to signal something just the other side of tomorrow.”

The title of the show, “Works of Love,” follows along this line of thinking that Dodge’s art practice, in connecting all the dots, represents a form of love.

“What happens if I use it to talk about, in a more general way, all of the odd energies that flow between things?” he asks.

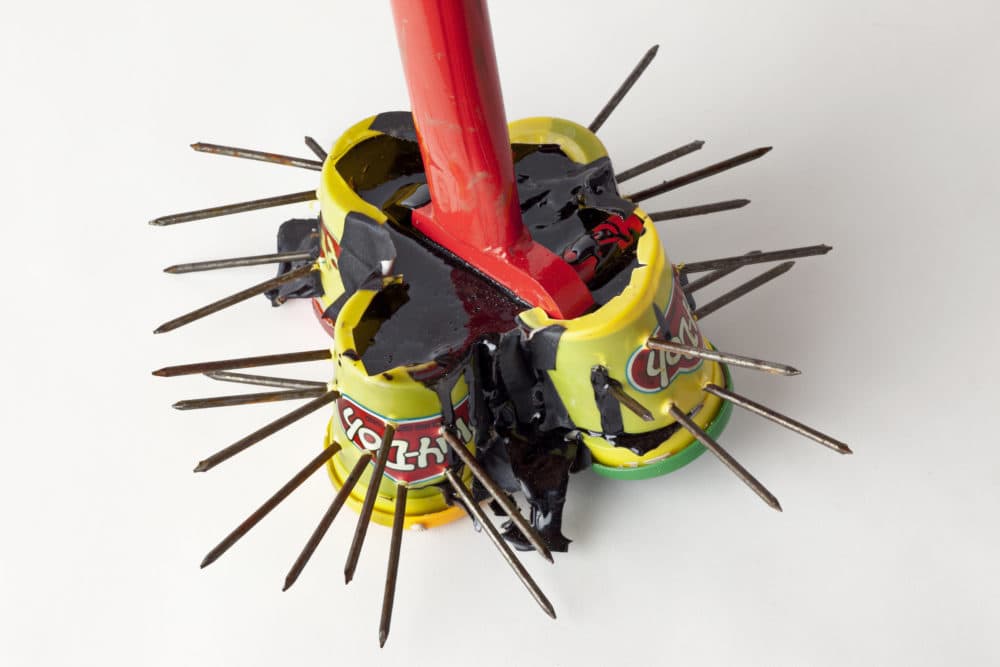

Although the show’s primary emphasis is on Dodge’s most recent “tabletop” assemblages, the show also folds in two other bodies of work — from his 2015 "Cybernetic Fold" show featuring his series “consent-not-to-be-a-single-being” as well as works from his earlier “Emergency Weapons” series. In his “consent” pieces, (titled after a phrase of French poet-philosopher Édouard Glissant who argued for the permission to remain undefined and uncategorized) bent rectangular resin consoles reminiscent of cartoon SpongeBob, sprout orifices and appendages that could stand in for vaginas, anuses, penises, scrotums or your choice of reference. You have Dodge's consent not to settle on any one definition. In his earlier “Emergency Weapons” series constructed after the passage of the Patriot Act of 2001, Dodge has created household “weapons” according to his own scoring system. The task was to build a weapon with items you might have on hand at home in less than four minutes, in case they were needed against an overreaching government. Dodge’s weapons don’t quite appear up to the job. He offers a forlorn dirty sock attached to what appears to be a ball of resin studded with nails, as well as three Play-Doh cans embedded with nails attached to a rebar bender. There are about 21 variations on this theme, each kind of funny, but also, in his words, “unspeakably violent but also bizarrely tender and pathetic. I think they're obviously timely again. Love and vulnerability are entwined.”

Throughout most of his work, and particularly in his “consent” series, Dodge exults in blurred lines. This may partially reflect his own personal history. Dodge was born female but now identifies as gender fluid and accepts the use of the male pronoun. The experience was recounted by his wife, the poet and critic Maggie Nelson in her memoir “The Argonauts.” Dodge was one of the founders of Red Dora’s Bearded Lady Café, a renowned performance space in San Francisco’s queer community. He also made a “queer buddy” film with director Silas Howard, known, among other things, for his work on the television series “Transparent.” Dodge enjoys reading the work of philosophers like Glissant and Maurice Merleau-Ponty who consider topics around identity and perception. On the faculty at CalArts, Dodge has an easygoing manner that belies his introspection and his fascination with such themes as materiality, orientation and interdeterminancy.

Dina Deitsch, curator of the exhibition at Tufts, says the show, originally shown at the nonprofit space JOAN in LA, seemed a natural one for tech-obsessed Boston.

“We are a tech driven community in Boston, and it's so nice how he undermines the caricature of technology,” she says.

As far as Dodge is concerned, technology is just the start of the conversation.

“I like it when I'm a bit confused, or answers are just out of reach, when I can't categorize things,” he says. “I like poetics, that is, when things can't quite be named and so continue to hum — that's the buzz of [always-fresh] relation: something that is always becoming, something always on the move instead of finding itself finished or coming to rest.”

In this vein, Dodge’s always-fresh work continues to hum along.

"Harry Dodge: Works of Love" is on view from Jan. 17 to April 14 at the Aidekman Arts Center on the Tufts campus in Medford. The opening reception will be held Thursday, Jan. 17, from 6 to 8 p.m. Dodge will have a public conversation with Amy Sillman on March 6 at 7 p.m. at the Remis Auditorium at the MFA.