Advertisement

Everything You Didn't Know You Wanted To Know About Marine Mammal Poop

Some people are content knowing only that the New England Aquarium has the world's largest collection of right whale poop, and that scientists are studying Northern fur seal feces.

Others hear those things and need more details.

If you fall into the latter group, here's a lightly edited transcript of my conversation with scientists Roz Rolland and Katie Graham, who study marine animal feces.

What does right whale feces look like?

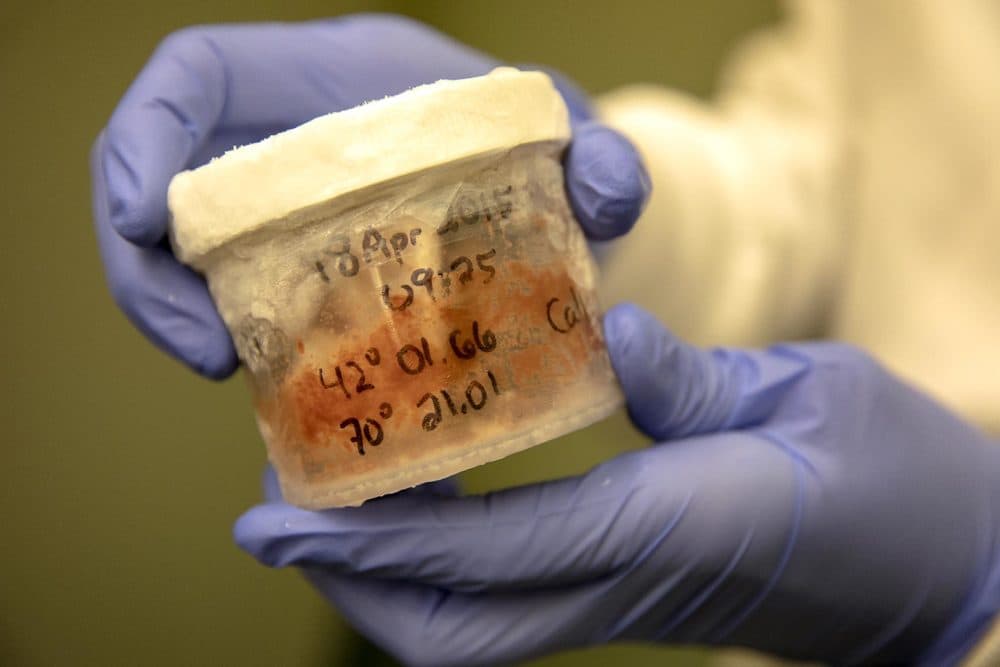

Rolland: It’s a bright, almost neon-orange color. No one has done a chemical analysis to determine what makes right whale poop this color, but my hypothesis is that it is from pigments within the oil droplets of their prey. (Right whales primarily eat Calanus finmarchicus, a particularly oily copepod.)

It is generally red in the spring and summer, but can also be brown at times. Any color change probably has to do with the age of the copepods and anything else the whales are eating.

What does it smell like?

Rolland: It’s indescribably potent. It’s sort of oily, greasy — it’s distinctive, that’s the best way I can put it. And it’s very strong, so you know when you smell it. There’s nothing else that smells like a right whale poop.

But if you had to liken it to anything…

Rolland: I’ve been asked this question for 20 years, and I still don’t have an answer for it. Other whales have distinct smelling feces, but not like the right whale. It’s just a unique smell — it’s not even fishy, it’s just unique.

It’s indescribably potent. It’s sort of oily, greasy -- it’s distinctive, that’s the best way I can put it. And it’s very strong, so you know when you smell it.

OK, so you see — or smell — some whale poop. What do you do next?

Rolland: Right whale poop floats, which is fortunate for me because otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to collect it. After we find a sample, we scoop it up in the net, drain the water off, put it in a little plastic jar, freeze it and bring it back to the lab.

How long does it float?

Rolland: At least a half an hour, but it depends on the amount of fat in the feces sample.

So you have to work with that smelly substance here in the lab?

Rolland: That’s right. Fortunately, we have fume hoods so we don’t fumigate everybody else in the building. But you do get used to the smell, surprisingly.

What are you looking for when you test samples?

Rolland: We measure reproductive hormones like estrogen, testosterone and progesterone. These can tell us if a whale is sexually mature, pregnant or lactating. We also study hormones that tell us about stress, and we look at thyroid hormones, which tell us about metabolism, metabolic rate and nutritional state.

How many samples do you have?

Rolland: A whole freezer full. We have almost 400 samples of right whale poop. We also have shark mucus and feces from manatees, bowhead whales, fur seals and other things we’re working on.

With any of these samples, we don’t need to use much for an individual test. A jar of feces is a lot of poop. With right whales, we’re dealing with a highly endangered species, and it’s hard to get these samples. Every little bit is precious.

OK, I have to ask, what is shark mucus?

Graham: It’s that slimy, filmy layer along the outside of a shark. Scientists use sponge scrubbers to remove small amounts of mucus for testing. It’s a new sample type we’re working with here, but it presents another non-invasive way to study hormones in marine animals.

What other methods is the aquarium using to study hormones in large marine animals?

Rolland: We’re developing methods to look at hormones in blow samples. Blow is when whales exhale. Like with feces, blow contains particles, compounds and chemicals that we can measure. The cool thing about blow is you can get repeated samples over time from the same individual.

Another recent approach is to look at hormones in baleen. Baleen are the keratin plates hanging from the upper jaws of baleen whales like right whales and bowhead whales. It turns out that hormones are deposited sequentially in them, so if you measure down the length of a baleen plate, it’s like looking at the rings of a tree. You can get a decade or more of hormone data on a whale. Of course, this is only from whales that have died, but it’s an extremely valuable timeline of physiological data that would be impossible to get any other way.

Recently, we studied baleen from a bowhead whale that was very badly entangled, thin and in poor condition when it died. There is a very clear enormous spike in two types of stress hormones that told us this whale was entangled over multiple months. You could see that signature very clearly in the baleen — it was amazing.

I think it’s important for people to know that this is not just a fun thing for us to study, but that we’re actually gaining a lot of valuable biological information in a non-invasive way.

Tell me about the fur seals you're studying?

Graham: We currently have three northern fur seals here at the aquarium that we collect two or three samples from every week. We’re trying to measure seasonal changes in reproduction, which should help us identify sexual maturity and develop a pregnancy test.

Working with our seals here at the aquarium allows us to collect a larger number of samples than we would working with wild fur seals, which is really helping us develop our technique. In the future, we hope to compare this information to wild fur seal feces to better understand why their population is decreasing.

What does fur seal poop look like, and how do know which seal it comes from?

Graham: It’s similar to dog feces. It’s about that size, about the same consistency. It smells a little bit stinkier than dog feces. A lot of their diet is squid and fish, so you definitely get a nice fishy smell off of it.

Because the seals live together, we had to get creative about the collection process. Our trainers may not always see which animal defecates, so we add a unique diet marker to each animal’s diet — Luna gets sesame seeds, Kitovi gets flax seeds and Chiidax gets lentils.

Our seals eat pre-frozen fish, so our trainers put the fecal markers into little gel capsules that they put inside the fish. When we find poop, it’s easy to know which seal it comes from.

It's not as easy as it sounds, though. Some of the initial fecal markers we tried — carrots and poppy seeds, for example — were overly digested or weren't easy to spot in the feces. Sesame seeds is something that worked from the very beginning.

Any last thoughts?

Graham: I think it’s important for people to know that this is not just a fun thing for us to study, but that we’re actually gaining a lot of valuable biological information in a non-invasive way.

Rolland: As a researcher and a veterinarian, the last thing I want to do is add another source of stress to an animal’s life. So the fact that we can learn so much without even touching them is a fantastic step forward in our ability to understand what’s compromising and affecting them.