Advertisement

National Book Award Winner Elizabeth Acevedo Owns Her Voice More Than Ever

When the poet and young adult novelist Elizabeth Acevedo was working toward her MFA at the University of Maryland, one of her professors asked her to pick an animal to write a poem about. As she recounts in “For the Poet Who Told Me Rats Aren't Noble Enough Creatures for a Poem,” her classmates chose blackbirds, deer, and nightingales. She, a native New Yorker, chose a rat. Her professor laughed.

She wrote it anyway, turning it into an ode to urban resilience: “even when they sent exterminators, / set flame to garbage, half dead, and on fire, you / pushed on ...You raise yourself sharp fanged, clawed, scarred, / patched dark—because of this alone they should / love you.”

The poem also countered the idea that only certain subjects are worthy of poetry. “How many writers were discouraged from writing authentically in the voice that they speak in and in the voice that speaks to their community?” she asked in a recent phone interview.

The YA landscape is crowded with dragons and magic, hackers and robots, mean girls and murderers. Acevedo’s characters have quieter escapes: cooking, poetry, family, friends. She honors the intensity and privacy of teenage feelings while also gesturing at the wider social structures that shape, sometimes invisibly, the lives of young people before they have the power to do anything about them.

Acevedo will discuss “For the Poet Who Told Me Rats Aren't Noble Enough Creatures for a Poem,” and other poems at a free event open to the public on Tuesday, Feb. 12 at 5:30 p.m., as part of a three-day residency program at Simmons University.

Late Thursday evening, Acevedo announced on her Instagram that HarperCollins had acquired two new YA novels from her. One of them, "Clap When You Land," is a narrative novel revolving around two girls who discover they are half-sisters after the death of their father. It's slated to publish in 2020. Acevedo also announced she'll contribute a story about a "bruja ... who strikes the first slave rebellion in the Americas" to Patrice Caldwell's YA anthology "A Phoenix First Must Burn."

If she had been a different kind of person, Acevedo says, some of the subtle messaging she received about what (and who) makes literature might have shut her down. “Once I got to college, I started seeing a bit more push back as to how I wrote, maybe the linguistic style I wrote in or the vernacular I wrote in. It was very rarely blatant, but it was just there: 'Oh, is Spanish necessary here?' Things like that.”

In her acceptance speech for the National Book Award, which she won for “The Poet X,” she spoke to the effect that discouragement had on her: “As the child of immigrants, as a black woman, as a Latina, as someone whose accented voice holds certain neighborhoods, whose body holds certain stories, I always feel like I have to prove that I am worthy enough and there will never be an award or accolade that will take that away.”

But her literary lineage brings confidence, and the knowledge that “My story is worthy, and the stories that I've been moved by, the writers that I love, have affirmed that my story is worthy. Toni Morrison, Julia Alvarez, Sandra Cisneros, Jacqueline Woodson — these writers showed me the way, even if they weren't the ones being taught in any of my higher ed experiences.”

As a new teacher, Acevedo worked to pass on that idea to eighth-graders in Prince George’s County, Maryland, who were approximately 78 percent Latinx and 20 percent black. “They had never had a Latinx teacher teaching a core subject. They'd never had an Afro-Latina teacher teaching at all.” And so, “When I was teaching there, I kind of started thinking, you know, I want to go back to writing. I think that I want to create the work that these young people are looking for on their bookshelves.”

The result is two young adult novels about Afro-Latina teenagers navigating familial and cultural expectations while finding their own voices. The first, a novel in verse called “The Poet X,” won a National Book Award, and shows Xiomara (it means “one who is ready for war”) finding the confidence to perform her poetry, while maintaining a relationship with her strict mother and dodging the chorus of sexual harassment that follows her wherever she goes. It also contains a searching exploration of faith and doubt:

When I look around the church

and none of the depictions of angels

or Jesus or Mary, not one of the disciples

look like me: morenita and big and angry.

When I’m told to have faith

in the father the son

in men and men are the first ones

to make me feel so small

That’s when I feel like a fake.

Because I nod, and clap, and “Amén” and “Aleluya,”

all the while feeling like this house his house

is no longer one I want to rent.

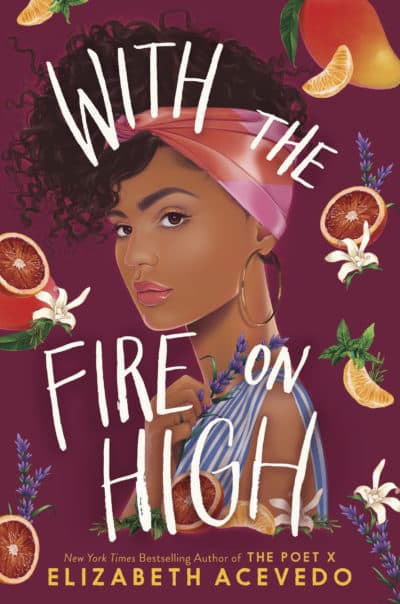

Acevedo’s next book, “With the Fire on High,” is slated for release in May, and follows Emoni, an Afro-Latina high-schooler from Philadelphia with a baby daughter, as she finds strength and creativity in cooking.

In both of Acevedo's completed novels, cultural expectations sometimes act as prisons for her characters. “I think of all the things we could be / if we were never told our bodies weren’t built for them.” Xiomara writes. Emoni, too, is tired of being put into boxes, racial and cultural: “[I]t’s like I’m some long-division problem folks keep wanting to parcel into pieces, and they don’t hear me when I say: I don’t reduce, homies. The whole of me is Black. The whole of me is whole.”

That refusal to diminish oneself is central to Acevedo’s full-hearted novels. They originate from a singular lens in a particular time and space, but they reveal how joy and grief coexist in the same person, how our life is tied to the lives of those around us, how we have the power to give and take happiness, how our experiences are inextricable from our identity, but do not dictate who we are. Acevedo's novels are guides to being greater than the sum of our parts.