Advertisement

Commentary

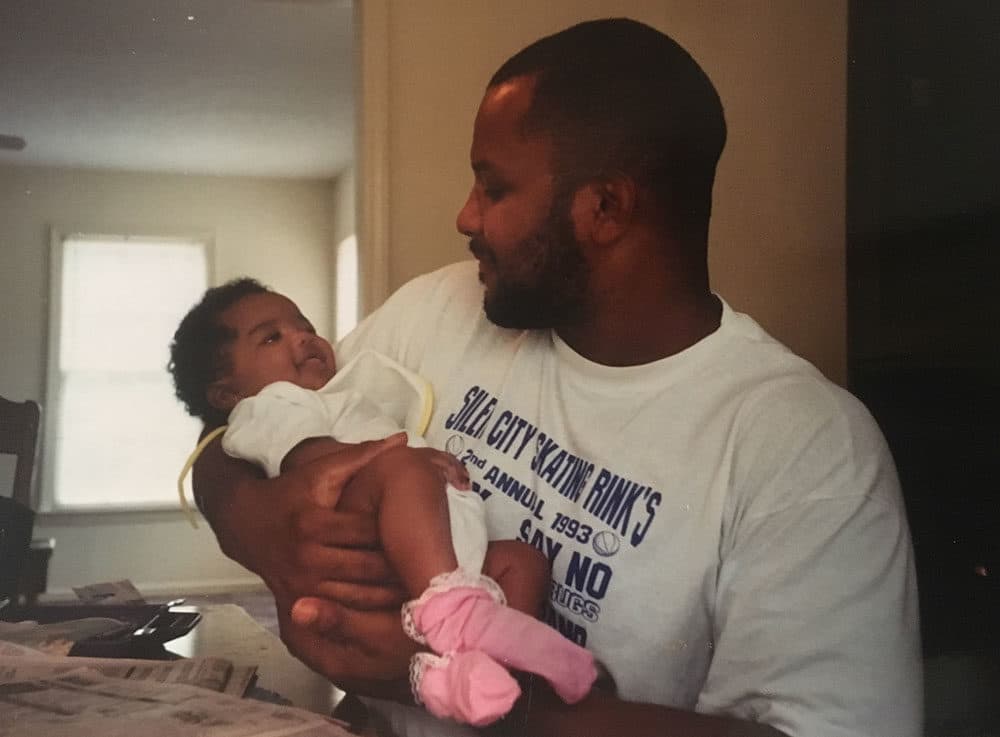

Saving Deddi's Life: What Donating Stem Cells To My Father Taught Me

I was the match.

My father had been diagnosed a few months ago with a potentially fatal leukemia, and it turned out my biology made me the best potential donor of the cells that could give him a better chance at survival.

“I’m sorry I have to make you do this,” he said over the phone. “But you’re basically saving my life.”

“You have nothing to be sorry about,” I reassured him.

And I really was deeply glad to help. As I'd watched the leukemia take its toll on him — causing him to rapidly lose weight, making him so tired he sometimes didn't even want to catch up over the phone — I’d wished I could do more for this man I loved so much. Now, I could.

But the truth was, I found the prospect daunting, too. I didn’t know much about donating stem cells and the risks involved, and neither did my family. No one we knew had ever done it. I’d heard stories about people donating their bone marrow, from which stem cells are also harvested, but didn’t know much about that either.

Would it hurt? How would I feel afterwards? Would there be any lasting health effects? What about bruising or scarring from the needles used to extract my blood?

That apprehension was at play in my family as well. My three paternal aunts had been tested first. One of them came close, but was relieved when doctors decided they might get even closer with my brothers or me because we were younger. We were each mailed swab tests to complete at home, which we admittedly dragged our feet on returning.

Advertisement

Clearly, though, the stakes made donating worthwhile. Only 30 percent of patients who need a stem cell donor can find a match in their family. The other 70 percent must search for one in a worldwide database of unrelated donors.

And our timing was good. It used to be that for the best chance at a good outcome, these potentially life-saving transplants were limited to those who could find perfectly matched donors. But over the past decade or so, medical research has advanced haploidentical, or "half-matched" transplants, making it easier for a patient's parent, sibling or child to become a donor.

This advance has been especially groundbreaking for patients of color. The odds of finding a full match are even lower for African-American patients, whose racially mixed genes increase the difficulty of finding a match, I learned.

Other racial minorities also have worse odds than Caucasians, who have a 75 percent chance of finding a perfect match.

Adding to the challenge, a number of barriers diminish the donor pool for African-Americans. The pool is smaller because black donors are often resistant to sign up. Some of that reluctance stems from general distrust of the medical system. It may also be the notion that donating marrow is a “middle-class, rich nation” thing to do, explains Dr. Jospeh Antin of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

“If you’re worried about where your next meal is coming from, or safety of environment, you’re not joining registries,” he says. Or the process of donation may be overshadowed by other priorities, like work or family, he adds: “You don’t have time to take off and do this stuff.”

Antin says a few years ago, it was estimated that bringing the number of African-American donors up to the level of other races would require 30 percent of the entire black population to join the donor registry — something he doubts will happen. But he says it's now clear that the key is not just having more donors — it's being able to do transplants with donors who are not as precise a match.

'Would You Do It?'

No one saw my dad’s diagnosis coming. Deddi — our nickname for him, influenced by the Southern accents we had as kids — was coaching a high school volleyball game when intense chest pains alarmed him enough to go to the hospital.

What was expected to be an overnight stay turned into a diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia. The news was a shock and instant life-changer for all of us.

He required a month and a half of chemo, but that wasn’t enough. He needed a stem cell transplant because his bone marrow had become diseased, and he had a FLT3 gene mutation that could ramp up the progression of his leukemia. The transplant had to happen within a very tailored window, while my dad’s cancer was tame enough to withstand it.

In the days leading up to the donation, I began self-injecting twice-daily shots of a bone marrow stimulant drug. They triggered bearable bone pain and fatigue, making me feel stiff and sluggish. Tylenol helped.

Instead of having the stem cells harvested from my bone marrow, which is the case for some donors, I donated via a process known as apheresis. This meant my blood was removed through a needle in one arm and filtered through a machine that collected my stem cells, which were eventually given to my dad. The remaining blood was returned to me through a needle in my other arm.

It took about seven hours, during which I had my mother and a team of extremely kind nurses to keep me company. The worst part was having two large IV needles stuck into my arm, both of which later had to be repositioned, but it was done quickly and carefully.

Shortly into the procedure, my anxiety was overcome by a feeling of serendipity. The transplant and my father's treatment were being done at the hospital of my alma mater, UNC-Chapel Hill, the place that had prepared me to face challenges like my father's illness with optimism and courage. That gave me the extra layer of confidence I needed to go through with the procedure.

Within a few days, I was feeling 100 percent again.

While my dad’s recovery is projected to take much longer, at least I gave him a big boost in getting there. I’ve also learned more about stem cell donations, and I am convinced we should all know more about them — and do more to help patients in need.

Millions of people have a chance to help patients by signing up at BetheMatch.org, and it's especially important for African-Americans and other minorities. There is always a need for people to sign up, because donors age out at 60, and some become sick themselves.

Recently, the religion professor and writer Alan Levinovitz tweeted:

He learned the same thing I did: The risks of bone marrow donation are far outweighed by the benefits — to the recipient, that is. The donors get the benefit of knowing they've helped save a life.

Deddi and I joke that this has been the reversal of my conception — I've helped to restore life to the man who helped give me life in the first place. But he's so much more than that.

In the days following my donation, I mowed the lawn at my childhood home for the first time. My brother taught me; we were splitting the job that had always been left to Deddi. As I flowed into the push-pull of the mower and breathed in the scent of cut grass, I recalled the countless spring and summer days when he would mow the grass as my friends and I played in the neighborhood cul-de-sac.

Every now and then, he’d break his rhythm by looking up and flashing a smile as we ran around playing tag, a reflection of the playful spirit behind his tough exterior. Whether in his work as a coach and teacher, or as a father, he's always struck a balance between getting a job done and finding joy while doing it.

These days, my dad is still going through treatment, and his body is adjusting to my cells. He’s often tired, but musters the strength to talk to me when he can. When I told him during a recent conversation that I'd be writing about the stem cell transplant, he pepped up.

“That’s a great idea!” he exclaimed, noting that it might inspire others to donate as well. “The fact that you prolonged my life … I can never repay you."

Of course, I don't need any repayment — except for him to get well.