Advertisement

At The Gardner, 'Big Plans' Looks At How Big-Thinkers Reformed Our Cities

They were four intellectuals famous in the world of culture and art. Frederick Law Olmsted was a journalist and social critic turned landscape architect. Lewis Wickes Hine was a sociologist-photographer. Charles Eliot was a landscape architect and city planner, and Isabella Stewart Gardner was an art collector and philanthropist.

Each had radically different interests, backgrounds and personalities, and yet, they had something in common.

They all had big plans. And not just for themselves. They had big plans for all of us.

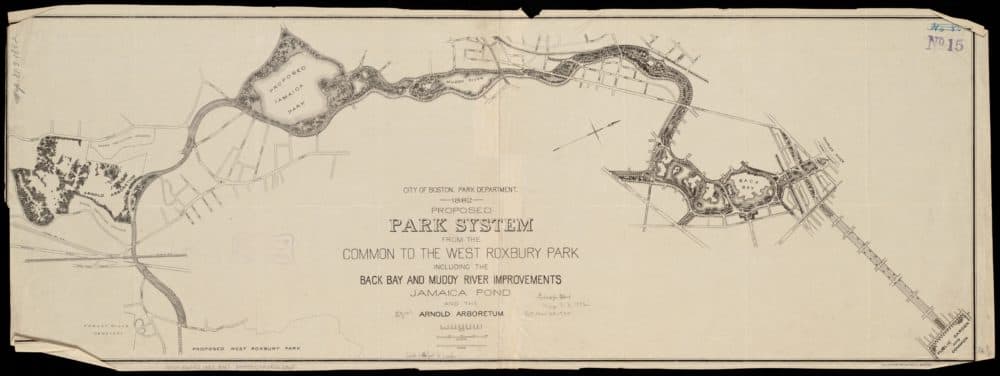

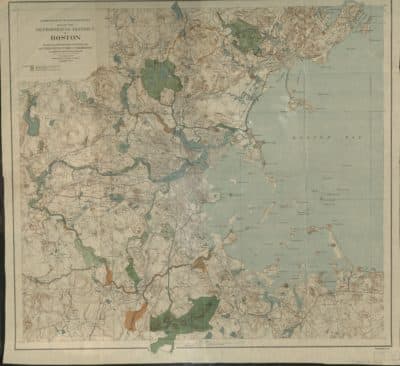

This is the starting point of “Big Plans: Picturing Social Reform,” on view at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum June 20 to Sept. 15. Centering around the social impact of four celebrated culture-makers, the exhibit provides a window into what it meant in 19th-century America to have one magnificent vision for civilization and to plow full speed ahead to implement it. We owe Olmsted for New York City’s iconic Central Park and Boston’s graceful Emerald Necklace, Eliot for helping to give us the Boston Metropolitan Park System, Hine for his work helping to implement child labor laws, and Gardner for allowing her beautiful faux-Venetian palazzo to eventually become one of Boston’s most treasured museums.

Their respective convictions could be regarded as forward-thinking and progressive, or perhaps paternalistic, depending on your point of view. The Gardner exhibit considers both sides, presenting architectural drawings, photographs, maps, city plans and other documents from the museum’s archives. Was their tireless work just standard Yankee noblesse oblige or were there deeper passions at work? Either way, cities like Boston, New York and Chicago look very, very different today thanks to their spirited determination.

“Even though they're different people working in different media with slightly different agendas, they all shared a commitment to address the social and environmental conditions of the industrial metropolis, with questions of immigration and questions of poverty and child labor and education,” says Charles Waldheim, curator of “Big Plans” and Ruettgers Curator of Landscape at the Gardner.

“Of course, they were in positions of influence and authority, but what they all shared was the idea that images and pictures could play and should play a central role in the process of advocating for social betterment.”

Advertisement

And what, we might ask, does their better society look like?

Certainly, in an ideal world, children do not pick through rags in trash dumps or bundle firewood for a living, as seen in Hine’s 1909 photographs of children at work and play in Boston tenements, waste dumps and back alleys.

On the other hand, a better city might look a lot like Olmsted’s 1857 “Greensward Plan” which he conceived with partner Calvert Vaux in a design competition for New York’s Central Park. (Although the original plan was lost, two original presentation panels are on display.) Or it might look something like Olmsted’s plans and maps for the Boston Back Bay Fens, the Muddy River, and the seven-mile stretch of verdant green space known as the Emerald Necklace.

An ideal city might be a place in which the conservation of scenic beauty is regarded as important as the conservation of paintings or books, as Charles Eliot argued. On display is the 1898 map of the Metropolitan Park District that he championed.

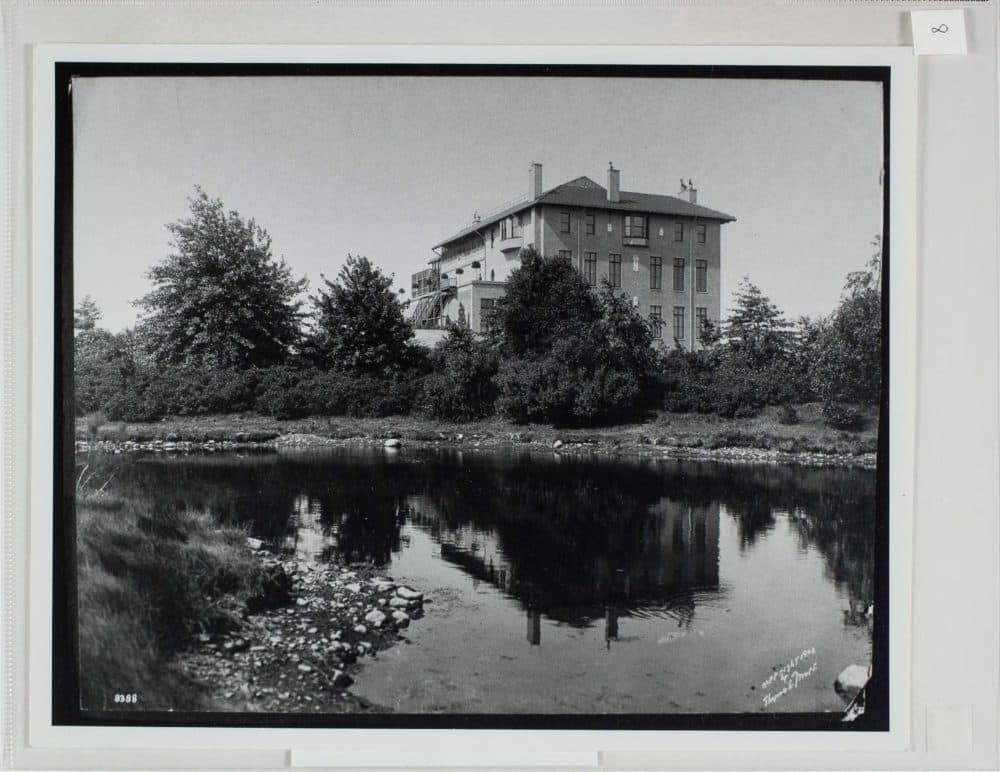

And certainly, any fine city would offer a space as beautiful as Gardner’s home for the appreciation and cultivation of art, which could be shared with a grateful public. “Big Plans” presents many of the original documents recording the purchase and construction of Gardner’s palace, including photos of the building as it was being constructed.

In any exhibit examining such radical reforms, there are naturally many points to consider. Yes, Gardner and the others were visionaries, but how inclusive was their vision, in the end? What happened to the German and Irish immigrant and African-American communities displaced to make way for Central Park in New York? In Boston, what happened to all the natural flora and fauna razed to reshape the muddy, swamp of Boston considered a public health threat? And if we wanted to make the same sort of sweeping changes today, could we? Or would we get stuck seeking to appease and accommodate every side?

Tackling these more contemporary issues is a video documentary included in the exhibit, collected by Sara Zewde, assistant curator of the show and research fellow at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C. Zewde spoke with four contemporary culture-makers whose practices are photographer, art collector and urban planner, rough parallels to that of the Gardner four. They include Pedro Alonzo, an independent curator and art consultant based in Cambridge; Katarzyna Balug, a social activist based in Boston; Stephen Gray, an assistant professor of urban design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design; and Leonardo March, a freelance photographer based in Brooklyn.

“I think a lot of things have happened since the 19th century,” says Zewde. “We've seen the traumatic effects of some big plans, like urban renewal or the national interstate system, and the impact that had. There's been a lot of reform in terms of the process of making plans. And so, the artists in the film really speak to that. They've crafted their practices within the context of the post-19th century post-urban renewal legacy.”

These days, big thinkers are less likely to sign on with the wholesale erasure of neighborhoods. Change happens with the drip, drip, drip of gentrification rather than in one fell swoop of big thinking.

Today, understanding exactly what that means is more nuanced than it once was. Visionaries still have big plans, but they’re learning to listen more before pushing ahead on their heroic projects.

“If you’re actually listening, you may realize there’s an idea that you didn’t have that’s even better,” Stephen Gray says in the documentary accompanying “Big Plans.” “But of course, then you bring your expertise to that idea to really provide the vision and the roadmap for achieving that vision and a direction that people can move together and with some excitement.”

“Big Plans: Picturing Social Reform” is on view at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum June 20 to Sept. 15.