Advertisement

Kū, A Fierce Living God For Many Native Hawaiians, Now Faces His Homeland

Staff quietly trickle into a granite-floored atrium in the Peabody Essex Museum’s elegant new wing. They mill about, hushed and excited, waiting to see an imposing, larger-than-life carving known as Kūka‘ilimoku, or Kū for short. Outgoing PEM director and CEO Dan Monroe is clearly excited for what's about to unfold.

“As anyone who sees Kū will understand, he is very powerful,” Monroe says. “He's fierce.”

Flaring nostrils, a gaping mouth and curled-up, jutting chin animate Kū's large head. His thick legs look ready to pounce. According to Hawaiian mythology, one of Kū’s many manifestations is God of War.

The deity was favored by King Kamehameha I, who unified the Hawaiian islands by 1812.

“He's a very complex god. He has not only a strong visual presence but a very strong spiritual presence as well,” Monroe says. “So he is being attended to by a number of practitioners of Native Hawaiian culture that we brought together to do this.”

“This” is a private ceremony to honor Kū and bless his new location. The carving is one of the first works to be reinstalled in PEM’s $125 million expansion. The girthy, grimacing, 6-and-a-half-foot-tall wooden sculpture has been in storage during construction. He's one of only three temple images (ki'i) of this kind in the world.

Kū is revered as a living god by many Native Hawaiians. The last time this rare object went through a similar ritualistic protocol was in 2010 when the trio of remaining Kūs were reunited for an exhibition in Honolulu at the Bishop Museum. (That museum houses a Kū; the third is owned by the British Museum in London.)

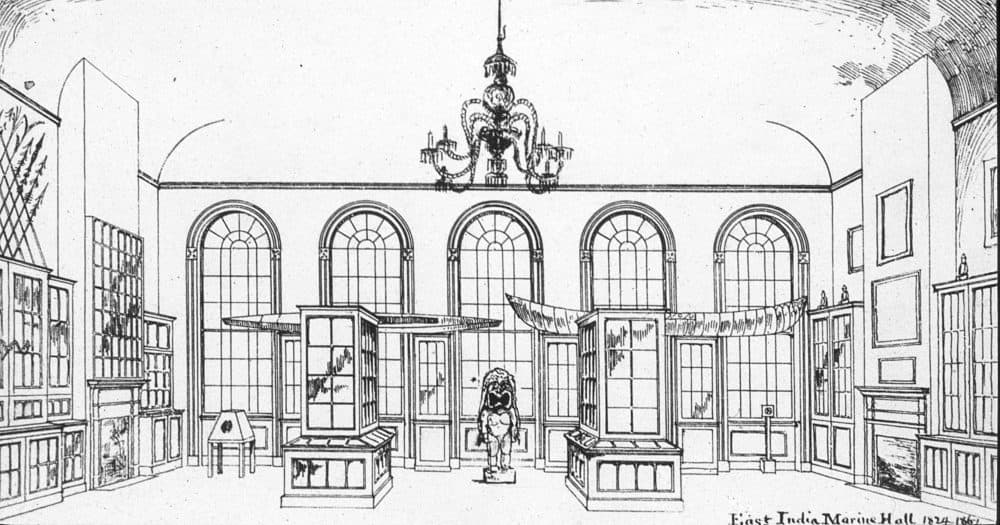

As we wait for the ceremony, a Native Hawaiian woman with braided hair, a wreath of dark seashells and bare feet sits quietly at the bottom of a stairway. Kū is on the second floor in a prominent place outside the East India Marine Hall.

The cultural practitioner walks toward us with a greeting, and some news.

“Aloha everyone. My name is Mehana,” she says warmly. “I will be ushering us up the stairs. They're almost ready.”

This ceremony is sacred for the practitioners, so I’m asked to shut off my recorder.

Soon the delegation’s series of chants rise and fall in the cavernous space to welcome Kū to his new home. His muscular form towers over the humans from a raised pedestal. Then I get the green light to record the final chant as offerings are laid at Kū's feet, including a bright-green lei made of native plants, and salts from all around Hawaii.

Advertisement

Marques Hanalei Marzan traveled from Hawaii to lead the ceremony. He's also cultural adviser at the Bishop Museum.

“We did a series of chants, first beginning with three chants that honored Hawaii,” he explains. “So the idea of bringing Hawaii to Salem with our presence, with our voice, with all of the things that we brought to connect Kū back with his homeland.”

Other chants were intended to awaken Kū, to mark the beginning of a new cycle, to create balance and to ask for inspiration and growth for all the work being done at the museum.

Kū was taken from Hawaii as waves of Christian missionaries arrived to convert the indigenous population in the 1820s, '30s and '40s, Marzan says. The Hawaiian monarchy denounced native religious practices and iconography was rejected and destroyed. But Marzan says countless objects survived. Many were collected by captains of trading ships passing through the Pacific islands.

“Whenever I travel to different places around the world I always think about what would happen if they actually stayed in Hawaii," he says. "Would they have still been around for us to see and experience today?”

Marzan says some Native Hawaiians strongly believe artifacts like Kū should be returned to Hawaii, but he's grateful this piece of his culture's history is being preserved at the Peabody Essex Museum. Here, he says, Kū can be an ambassador for Hawaiian people. He calls the museum a steward.

"Being from Hawaii, and having the value systems of the Pacific, we understand that just because you are the steward of something doesn't mean you own it," Marzan says. "You have a responsibility to care for that on behalf of the people and community that it comes from."

“What we're doing is honoring Native Hawaiians’ living relationships that they have with Kū,” Karen Kramer told me after the ceremony. She's the museum's curator of Native American and Oceanic Art and Culture. “How can we be better caretakers, always lifting him up and letting him be the amazing star that he is?”

Kū entered the museum's collection in the 1840s. Kramer says a donor named John T. Prince wrote a letter to the East India Marine Society stating the temple image was procured from a converted Native chief who had planned to destroy it. A ship's carpenter was ordered to remove Kū from his tall pole. The effigy would later be installed in the Salem museum in 1846.

For Kramer, it's impossible to know for sure if Kū would’ve been burned — or not — if he had stayed in Hawaii.

"Did we save him? I don't know," she says. "But have we taken care of him since we've had him? Yes."

Like other U.S. cultural institutions that receive federal funding, the Peabody Essex Museum complies with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act — or NAGRPA — a legal mechanism enacted in 1990 to help return human remains and sacred objects to indigenous communities. PEM director Dan Monroe was instrumental in NAGRPA's creation.

According to the museum, a NAGPRA right of possession claim for Kū was submitted by Hui Malama I Na Kupuna 'Oh Hawai'i Nei (Group Caring for the Ancestors of Hawai'i) in the '90s. After a review of records and dialogue with the PEM, the request was withdrawn, according to PEM officials. The museum says it will continue to work closely with Native Hawaiians to care for the sculpture. In the new wing, Kramer says, thousands of visitors will be exposed to Kū's history and artistry.

“If you follow the lines of his headdress [braided hair] from the tip of his head all the way down — and it hangs almost as low as his hands — that's all one piece of wood,” she marvels. “And it is an unbelievable work of art, and you can feel power emanating from him.”

One person who experienced Kū's power up close during the ceremony is Native Hawaiian Kamuela Werner. He's one of five Native American Fellows studying at the museum this summer.

“The past and the past became ever so relevant — accessible — as if he was reaching his arm out to me and bringing me back — and reminding me about the present and the future — all connected with the past,” Werner muses. “So that's what it felt like.”

Werner's field of study is anthropology and one of his goals is to help elevate Hawaiian historical memory. He says he's been pleasantly surprised by the cultural sensitivity and respect the museum has shown for Native Hawaiian practices and toward the important sculpture.

“How Kū was taken out of the box, brought to the place, all of the ceremony,” he recalls. “I hope the relationship grows and that it engenders more types of events with other cultural objects."

The museum staff and their Hawaiian guests conclude the ceremony with a midday meal. Before sitting down, the visiting delegation’s Marques Marzan smiles and says he's thankful to see Kū standing proudly in a prime window spot where he can look outside and see the world again.

“See the sky,” Marzan hopes, “maybe not feel the rain, but you know he can definitely see the rain falling, see the wind blowing through the trees.”

Now Kū is also facing west, toward his homeland.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the year when the effigy was installed in the museum. We regret the error.

The Peabody Essex Museum’s new wing opens in September 2019.

This article was originally published on June 25, 2019.

This segment aired on June 25, 2019.