Advertisement

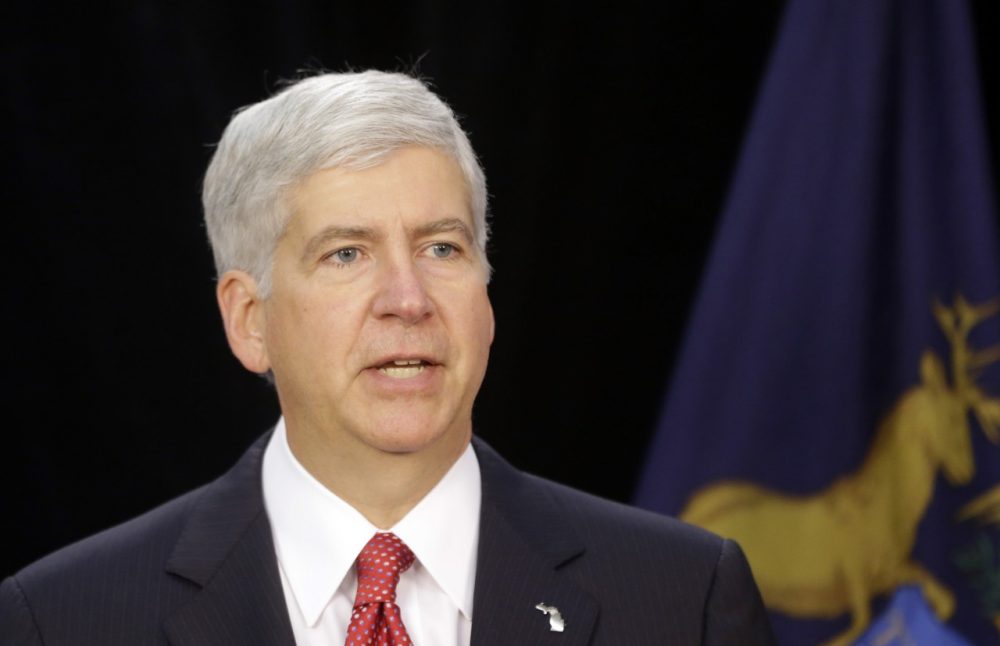

For Many, Rick Snyder Is The Man Who Poisoned Flint. Harvard Believes He Has Lessons To Teach.

Rick Snyder — the two-term former governor of Michigan who oversaw the emergence of the water crisis in Flint — is joining Harvard Kennedy School’s Taubman Center for State and Local Government as a senior fellow.

But hours after the appointment was widely announced, dozens of scholars, activists and alumni pushed back online under the hashtag, “#NoSnyderFellowship” — citing the governor’s oversight role as that crisis began:

Shortly after taking office in 2011, Snyder appointed powerful emergency managers to oversee the cash-strapped municipalities of Detroit and Flint. And those managers promoted Flint’s temporary turn to the Flint River for its water supply in 2014 as part of a cost-saving measure.

Last year, a University of Michigan biologist found that an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease that killed at least 12 Flint residents was likely due to inadequate treatment of that water. Also during the crisis, thousands of children were exposed to toxic levels of lead. Lead poisoning can cause setbacks in brain development, irritability, anemia and other serious health effects.

Art Reyes III earned his master’s degree in public policy from the Kennedy School just as that crisis was breaking out, and now heads We The People Michigan, a political organization formed in response to the crisis. Reyes says people in his hometown still hold Snyder personally responsible for the crisis.

“Governor Snyder knew about the lead leaching into the water system months before that was made public,” Reyes said. “It's certainly not the kind of leadership that should be awarded by a prestigious institution like the Harvard Kennedy School.”

The former governor comes to Harvard under a cloud of suspicion. In April, a federal judge reversed a prior decision and found that Snyder did engage in a cover-up of the water crisis. And at the beginning of June, Michigan law enforcement seized more than 60 phones and hard drives used by Snyder and his staff as they relaunched a criminal investigation.

In an email, Taubman Center director Jeffrey Liebman wrote that he expects Snyder, who started Monday, to bring “significant expertise in management, public policy, and promoting civility” to classrooms, seminars and talks.

Despite the backlash, Kennedy School officials aren't planning to reverse Snyder’s appointment, or to give any attributable public comment on the decision. One involved official said that despite his failings, Snyder — a fiscal conservative from the Midwest — brings life experience and perspective to a campus that might otherwise have a liberal or coastal skew.

The official asked not to be named, saying he was honoring an institutional decision not to give quotes on the matter.

That official confirmed that Snyder sought a similar fellowship at the University of Michigan’s Ford School of Public Policy only to be denied, apparently due to his record in Flint. Rick Fitzgerald, a University of Michigan spokesman, did not confirm or deny that decision, but said that Snyder "has engaged in a number of activities on our campus... and we continue to explore additional opportunities for further engagement."

At Harvard, the official said, Snyder should expect to face tough questions about his handling of the Flint crisis in a variety of settings.

The calls to disinvite Snyder come as President Trump and many in conservative media accuse American colleges and universities of growing hostility to free speech — or to conservative views. Many on Harvard's campus are trying to make a practical objection to Snyder's appointment.

Anna Nathanson, a third-year student at Harvard Law School, said her objection was not to Snyder's political views, but to his “catastrophic” effect on public health in a city of nearly 100,000 people.

“As students, I would think we’d want to learn the right lessons,” she said, adding that the Kennedy School could instead have sought out activists who fought for justice in Flint.

This is only the latest Kennedy School appointment to trigger an outcry.

Two years ago, hundreds of alumni rebelled as its Institute of Politics announced that former Trump aides Corey Lewandowski and Sean Spicer would become one-year fellows. Those invitations were not rescinded, but the IOP did reverse itself on another 2017 fellow, the whistleblower Chelsea Manning, after then- CIA head Mike Pompeo and a former CIA director characterized Manning as a traitor.

The Kennedy School official noted a distinction between Manning's case and Snyder's: Manning’s fame depended mainly on being convicted of a serious crime — turning classified material over to journalists. Meanwhile, Snyder has other career experiences — an eight-year governor and the former president and interim CEO of Gateway Computers — and has not been formally charged with a crime.

But the official added that the school would revisit Snyder’s appointment if charges are brought against him as part of the ongoing state probe.

This article was originally published on July 01, 2019.