Advertisement

Small Colleges, Big Challenges

Serving First-Generation Students May Be Key To One Small College's Survival

Part 3 in a series.

If you imagine a small college in New England, you're likely to imagine a place like Pine Manor College. Founded in 1911, and now set up on 60 acres in Brookline, the campus has tree-lined walking paths, rolling fields and a headquarters in a converted mansion.

And yet over the past several decades, the college has come to serve a population that's historically been underrepresented at institutions like Pine Manor — made up overwhelmingly of low-income students and first-generation students.

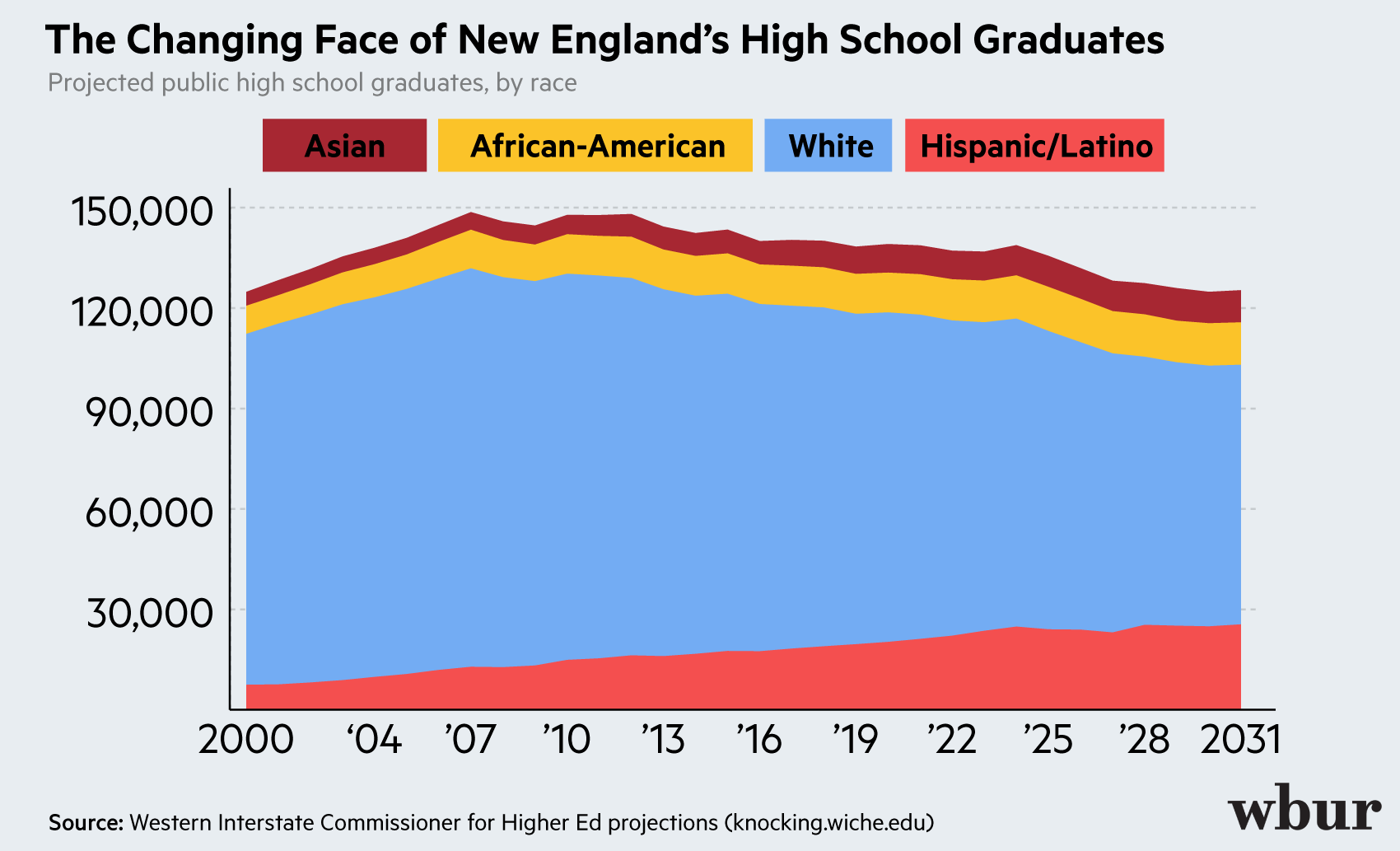

At a moment when the region's population is expected to grow both older and more diverse, the small college is trying to point the way.

Lisa Rodrigues never expected to enroll at Pine Manor College. And once she was here, she wasn’t always sure she’d make it through.

"I thought I wouldn't be able to stay," Rodrigues said. The issue was her junior-year bill. "I was gonna owe close to $8,000. My parents said, 'I have nowhere to pull, for you to get this.' "

Rodrigues found a way, with the help of family, and she graduated in 2006. Ten years ago, she returned to Pine Manor again, as staff, determined to give back. She's now the associate dean of student affairs.

But she remembered being on the college's tranquil Brookline campus. Rodrigues, from Brockton, was a first-generation student — like 85% of Pine Manor’s current enrollment. Then and now, that comes with challenges. Not just money concerns, but also daunting academic demands and occasional feelings of isolation.

"It gets really hard, really fast," Rodrigues said. "That's where we kind of step in to understand their struggle ... and then support them through it."

Advertisement

In that way, Pine Manor's present may provide a glimpse of other colleges' futures.

Due to long-term trends — like widening inequality, changing admissions practices, immigration and the increasing importance of a college degrees — first-generation and low-income students comprise a larger and more visible share of private-college enrollment.

But Anthony Jack, a sociologist at Harvard who studies disadvantaged students at elite colleges, said it's not enough to admit those students in greater numbers: "You still have to pay attention to the way in which norms that operate in higher education ostracize lower-income, first-gen, or non-traditional students."

In his book, "The Privileged Poor," Jack singled out the confusing norm of office hours — a key to facilitating relationships with professors. But landing internships, forming clubs, building networks, those norms, too, can be hard to master, and many colleges still fail to teach them.

Interested in more education news? Join our WBUR Ed Talk Facebook group.

The result has been long odds for those students. A study published earlier this year by the Pell Institute, which studies equity in higher education, found that of first-generation students who were also from low-income households, only 21% got a bachelor's degree within six years of their 2003-04 enrollment. And in a more recent cohort, around 36% dropped out within three years.

When he took over as Pine Manor president three years ago, Tom O'Reilly inherited a mission to beat those odds. But, with his background in business, he embraced it with entrepreneurial zeal.

For one thing, his team rewrote the job description of every member of staff — from faculty to custodians and coaches — so that it begins: "The purpose of this position is to grow the graduation rate at Pine Manor College by ... ." O'Reilly said members of staff work with their managers to figure out how they might help on that one key metric.

The college's admissions team has started to grade applicants based on character traits like "aspiration" and "persistence." And the average net price of attending Pine Manor remains among the state's lowest for a private institution — at just shy of $21,000 a year.

Sophomore Ivan Hernandez was drawn to campus by the generous financial aid; he's a first-generation student, born in El Salvador. But for the nature-loving biology major, there was another attraction: "The environment, the trees — the pine trees — I fell in love with that."

Like many of his classmates, Hernandez works long hours during the week. He commutes by bus from Norwood to Chestnut Hill, and returns in time for his restaurant job.

He has relied on the tutoring the school provides, and the understanding of his professors.

"If you send in an email saying, 'I'm going through this right now, and I'm not sure if I'm going to focus so much on this test — can I do another day?' They will change the deadline," Hernandez says. "They accommodate things."

Due to ongoing attrition and turnover, it's difficult to say how many students Pine Manor enrolls, but it hovers around 300 students. That small size makes them vulnerable, but it also allows them to be accommodating.

For the first time this summer, the school welcomed students' entire families to campus for freshman orientation. And they keep room for "comeback" students — who might leave campus to have a child, work for a bit or deal with another of life's inevitable detours.

College officials say their efforts are paying off. Current first-years, staff say, seem uncommonly engaged in class and at home on campus. And the graduation rate has hit a recent high of 43%. That's a few ticks above the national average for the students they serve.

And yet that means enrolling at Pine Manor is still worse than a 50-50 proposition — despite the supports, the majority of students still aren't graduating. Lisa Rodrigues called that "the thing I grapple and struggle with the most."

"I never want to see a student [acquire] debt, and then leave with nothing," Rodrigues said.

Then there's the college itself. This new phase of Pine Manor's mission has not been a comfortable one.

Its endowment has never regained the value it had in 1994, just before its second phase began. And its financial fortunes depend, in part, on revenue from services on campus: a childcare center, and the use of the grounds for weddings and events. The New England Association of Schools and Colleges, an accrediting agency, has twice placed the college on probation, then twice removed the label. The college's long-term future is far from certain.

But Rodrigues and other members of staff hope people come to value the college for what it is, and what it hopes to be: a college built to serve the students who have the most to gain from college.

Do you have questions about small private colleges in Massachusetts? Fill out the form below:

Illustration by Chris Cerrato for WBUR.

This segment aired on October 22, 2019.