Advertisement

Lawmakers Consider How To Curb 'Hot Spots' Of Low Vaccination Rates

ResumeIf her young children are ever at extra risk for contagious diseases because their school's vaccination rate dips too low, Massachusetts state Sen. Becca Rausch wants to know.

The same goes for Rep. Maria Robinson, also a mother.

"All communities have the right to know if they're at risk of contracting one of these deadly diseases that many of us had believed to be completely eradicated, and yet we're seeing pockets pop up all over the country," she said.

Robinson, Rausch and others spoke at a State House press conference this week on behalf of a new bill that would bolster the state's vaccination system. It would require all schools to report their vaccination rates to the state — reporting is currently voluntary — and to notify families if their rate falls short, among other provisions.

With yet another Disneyland measles scare in the news this week, the bill aims to address worrisome trends at both the state and the national level.

Massachusetts has one of the highest vaccination rates in the country, with 96% of kindergartners fully immunized, but vaccine exemptions based on religion are on the rise, with just over 1% of kindergarten students claiming a religious exemption.

The national picture is similar: The overall vaccination rate is high, at about 95%, but the exemption rate has risen slightly to 2.5%, with most exemptions for non-medical reasons, the CDC reported last week.

Then there are the "pockets" of especially low vaccine rates Rep. Robinson mentioned. The CDC found that in Idaho and Oregon, more than 7% of kindergartners have exemptions from at least one vaccine.

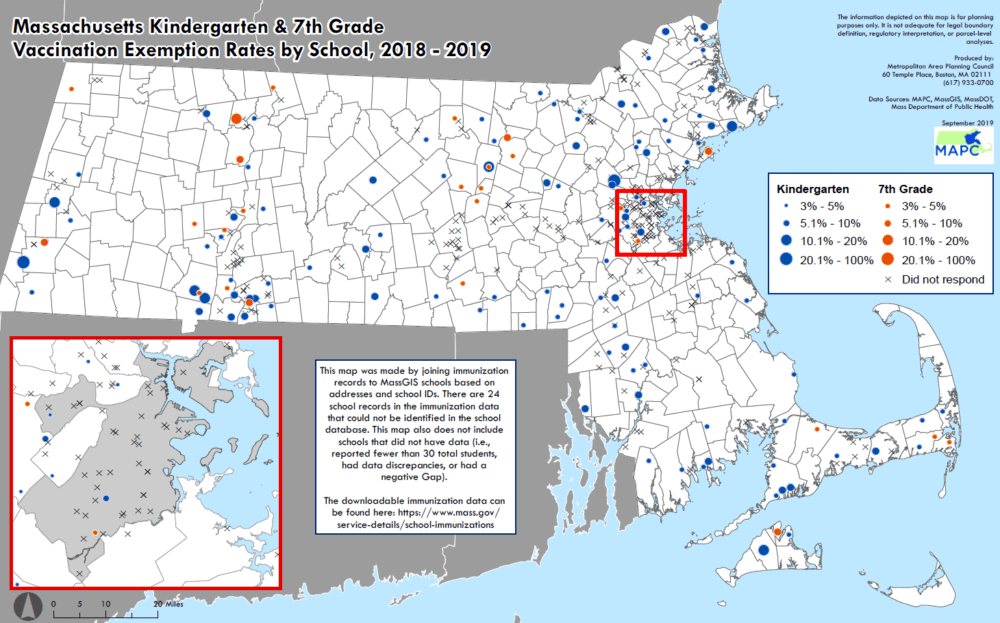

Massachusetts has low vaccination clusters as well, including several schools where exemption rates top 20%. A map by the bill's sponsors (above) finds hundreds of schools that either failed to report their vaccination levels or fall below "herd immunity" — levels so high that even those who can't get vaccinated are protected.

"Outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases occur in 'hot spots,' in places where groups of people have not achieved the immunization rates that are necessary to keep diseases from spreading," said Dr. Regina LaRocque of Harvard Medical School as she spoke in support of the new bill.

The state also has major gaps in its data: About 16% of kindergartens and 23% of seventh grades did not respond to the state's 2018-2019 school immunization survey, officials say.

The new bill would ensure public health officials could gather full vaccination data, monitor rates and handle exemptions, Rausch said.

Massachusetts "led the nation 200 years ago with the first mandated smallpox vaccine," she said. "So it is not surprising to me that many people assume we are still a leader in immunization policy. Unfortunately, that assumption is wrong."

Her bill is not the only proposal now making its way through the Legislature. Another bill would simply do away with vaccine exemptions on religious grounds, as a handful of states — most recently New York and Maine — have done amid rising concerns about measles outbreaks.

"It removes the religious exemption since we've seen an all-time high in the use of religious exemptions here in Massachusetts in the past year," says Rep. Andy Vargas, its lead sponsor.

Some parents who choose not to vaccinate use the religious or "personal belief" clause, which most states still have, to exempt their children from state school vaccination requirements.

Vargas welcomes some aspects of the bill that would maintain the religious exemption, he said, including the improved reporting requirements. But "we really need to go to the heart of the problem, and have the courage to do so, and be a state that is willing to respect the science and what our doctors and pediatricians are telling us," he said in a phone interview.

His bill has not had a public hearing yet but has drawn early resistance from some activists. Though the Rausch bill would allow religious exemptions, it was already drawing challenges as well at its State House presentation this week.

Advocates questioned the provision in the bill that would require parents who seek a religious exemption to acknowledge the risks of foregoing vaccines. They also questioned allowing "mature minors" to be vaccinated without parental permission.

"There's a lot in the bill that is highly concerning to me," said Candice Edwards from the advocacy group Health Choice for Action, who said her son had a reaction to a vaccine but his doctor had refused to sign a medical exemption.

"I would never sign something to say I'm knowingly causing harm by not vaccinating my child," she said.

Even if that acknowledgement of risk were not required, she said, she would not support the bill, and instead wants to see more research on which children are at heightened risk for reactions to vaccines.

In states that have banned non-medical exemptions, Rausch said, "many, if not all of those laws are now caught up in lawsuits. I don't think we should wait to implement many of the important public health infrastructure policy changes — brand new public health policy that we are creating by virtue of this bill — for five or maybe even 10 years of lawsuits to play out."

In the coming months, Rausch and Vargas expect to address their differences in the public health committee.

As sponsors of vaccine bills, they are far from alone. Such bills are in play in many state legislatures and are often contentious. California, which passed one of the country's strictest vaccine laws in 2015, has just tightened its vaccination rules still further, including on medical exemptions.