Advertisement

How Author Erin Morgenstern Pulls From A Background In Theater For Her Storytelling

As the daughter of a librarian, Erin Morgenstern spent a lot of time at libraries. She has vivid memories of the layouts of the two libraries in her Massachusetts hometown of Marshfield. The tiny library not far from where she grew up didn’t look like a library at all — it masqueraded as a house. But the children’s section of the big town library left an even larger impression. Upon entering the building, she would dart to the side, down the stairs, grab a picture book, then plop on the carpeted steps to read. Over the years, the librarians in Morgenstern’s life all blended together as “magical useful people who let [her] have books.”

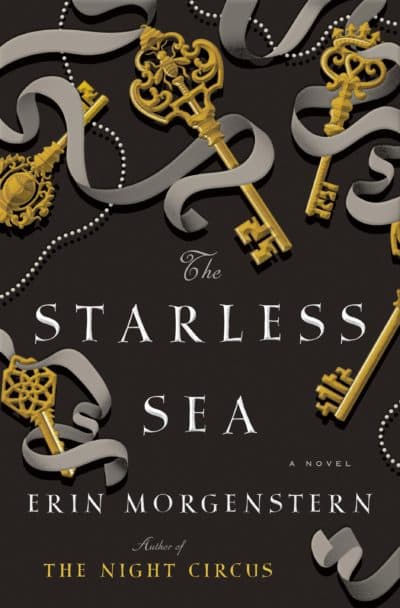

In Morgenstern’s sophomore novel, "The Starless Sea," protagonist Zachary Ezra Rawlins is also transported to a different world thanks to libraries. By chance, he finds a book in his Vermont college library that somehow describes an encounter from his own childhood that he has never told anyone about. Now he’ll do anything to discover how it got there.

Scouring the internet for clues about the symbols from book’s cover — a sword, a key, and a bee — leads him to a masquerade ball in Manhattan, where he’s offered a choice: Will he follow the instructions from a handsome stranger that have unforeseeable consequences, or will he return to the safety of Vermont and pretend like none of this ever happened? For someone who has always felt like he was missing the chance to be a part of something greater than himself, it hardly feels like a choice at all, but it’s important that he made it. By choosing the unknown, he becomes privy to a secret ancient underground “labyrinthine collection of tunnels and rooms filled with stories.” In other words, a library.

Zachary’s descent to this library (also known as the Harbor of the Starless Sea) is perhaps a nod to some of Morgenstern’s favorite stories from childhood, “Alice's Adventures in Wonderland” by Lewis Carroll and “The Egypt Game” by Zilpha Keatley Snyder. Zachary is pushed into a painted door rather than falling down a rabbit hole, but he still finds a mysterious vial he has to drink before he can proceed. The influence of “The Egypt Game” is more abstract. Those characters had created their own adventures in their neighborhood, which inspired a young Morgenstern to construct Egyptian temples in the woods behind her house.

Zachary is a graduate student in Emerging Media, which means he procrastinates working on his thesis about video games by reading books. “I knew I wanted him to study something book-related without being an English major,” said Morgenstern. The solution was to have him study something story-related instead. That answer came to her when she played "Dragon Age: Inquisition." This was the first time Morgenstern played a game where the choices a player made mattered to story. “It’s a butterfly effect narrative,” she said. “The stories are personalized depending on different choices. You can’t change direction. People can die.”

“The Starless Sea” is not a choose-your-own-adventure book, but it does wrestle with the theme of free will versus fate. At first, the book’s structure makes the case for a classic hero’s journey spun by mythic destiny. Morgenstern intersperses passages about Zachary Ezra Rawlins with other sections from the book he is mentioned in. Each side story has the familiarity of a fairytale without feeling like a retelling of well-known lore. The reader is left to wonder — if Zachary is real, then which of the other stories might be real, too? If this book was written before Zachary was even born, does he have control over his own actions?

The book confirms something Zachary has long suspected, which is that “he was given something extraordinary and he let the opportunity slip from his fingers,” which clues the reader in that he could walk away if he wanted to. But for readers like Zachary who had searched their wardrobes for Narnia or dutifully awaited their Hogwarts letters, realizing they had unknowingly passed up the opportunity to pursue a Library of Alexandria as old as time would be their worst nightmare. Thankfully, Zachary gets a second chance to unlock that door to a world of imagination and possibilities, only to discover the Starless Sea is in grave danger.

The interlocking chapters of fairytale-like backstory and modern hero’s journey are a labyrinth in themselves. This is reflective of Morgenstern’s writing process. She admitted that she is “not an outliner,” so she will find the story she wants to tell by writing different iterations, backstories, and side stories in bits and pieces. She has to live in that world and explore. The result is a reader’s playground of rich language, seductive settings, and mysterious characters.

Morgenstern learned how to set a scene from her extensive background in theater. She majored in it at Smith College, so she was exposed to a little bit of everything. She acted, she stage managed, she directed, she studied lighting design. By doing in depth scene studies over half a semester, she learned how to dig deep into characters like Hamlet. Through directing an adaptation of “Through the Looking Glass,” she learned how to construct an ensemble piece. And by constructing the lighting in a given setting, she learned how to establish mood in a way that most authors would overlook.

The biggest difference between books and theater for Morgenstern is the decision-making process. In any theater situation, there is always collaboration between actors, designers, directors, and more. For writing, Morgenstern takes on all of those roles herself, “which takes a lot longer to write and rewrite until it’s book-shaped.” She’ll write draft after draft until she gets to the point where she’s emotionally ready to let the story go, and that’s how she knows she has her ending. She attributes this to the Leonardo da Vinci quote, “Art is never finished, only abandoned.”

Morgenstern started writing her debut novel, “The Night Circus,” when she didn’t know what next step she should take in theater. She knew she liked writing from playwriting and creating dialogue, but when she sat down to write in brief spurts of page or two at a time, she would quickly hate what she had written and stop before it got much further. National Novel Writing Month turned out to be exactly what she needed to get 50,000 words on the page in 30 days, so she could get over the hurdle of getting something finished. “I had to write everything wrong before I got it right.”

After “The Night Circus” did better than Morgenstern “ever could have dreamed,” it gave her a “slight” confidence boost. “You never feel like you know what you’re doing,” she said. But when the pressure to write another book was mounting and a few projects didn’t pan out, she thought about why she wanted to write another book. “I was writing an analysis about why I was writing in the first place,” she said. Then she came across an idea in her notebook about underground library, and it clicked. It was a space she wanted to play in, a world she wanted to explore. Now she has created a book about stories for the next generation to curl up on their library stairs and let themselves be transported to a world of wonder.

To celebrate the release of “The Starless Sea,” Erin Morgenstern will be in conversation with Liberty Hardy at the Coolidge Corner School on Tuesday, Nov. 5 at 6 p.m. (Tickets are available here.)