Advertisement

At The Distillery Gallery, 'Dear So-And-So' Explores Artistic Collaboration And Surprise

We all look forward to receiving packages in the mail. But what if you’re an artist charged with collaborating with another to create a piece of art, and what you receive in the mail from your partner-in-art is a dish towel with the words “DISCO BALL” woven into it?

“When I first got that package I was like, ‘What?!?’" recalls Medford-based painter John Skibo. “I played around with it in the studio and tried to figure out how to make it my own. Like a good dish towel, I got it wet, then draped it over a bust to see what it would look like. It was beautiful and a little ridiculous but for some reason, reminded me of the Shroud of Turin.”

Skibo, who says he’s attracted to materials that fold and drape to create light and shadow, made a painting of a head draped in the dishtowel. Created in collaboration with Philadelphia-based artist Chloe Isadora Reison, the painting — now on view as part of the exhibit “Dear So-and-So,” running Nov. 25 through Dec. 29 at the Distillery Gallery — is a little grotesque, a little absurd, and yet alludes to something mysterious and unknowable. What lies beneath the cloth?

“I love that something as simple as a dish towel can become art,” says Skibo.

Reison, the associate director for the Sachs Program for Arts Innovation at the University of Pennsylvania, does installations revolving around anonymous spaces like waiting rooms, lobbies and airport terminals. She says the resulting collaborative effort “Disco Ball Shroud,” continues themes that have intrigued her over her career. Reison reacted to Skibo’s work by creating her own sculpture of an object draped in the kind of white shrink wrap you see covering boats during the offseason.

“Rather than looking at the spaces and objects themselves, I am thinking about notions of masking, shrouding, covering up — the act of rendering something anonymous or unrecognizable and the interesting tension inherent to that act,” says Reison. “For as something is covered up, its significance is at once obscured and made visible. We shroud to protect, to honor in ritual and memorialize, as well as to censor or remove from view.”

“Dear So-and-So” is built around the tantalizing notion of exactly what comes about when two artists are asked to create a work of art by collaborating, sometimes together in a room and often independently, at a distance. Curated by Cambridge-based artist Mary E. Lewey and Helen Popinchalk, a full-time artist and adjunct professor of screen printing and print-making at Simmons College, the show unveils collaborations that are intriguing, funny, and often unexpected.

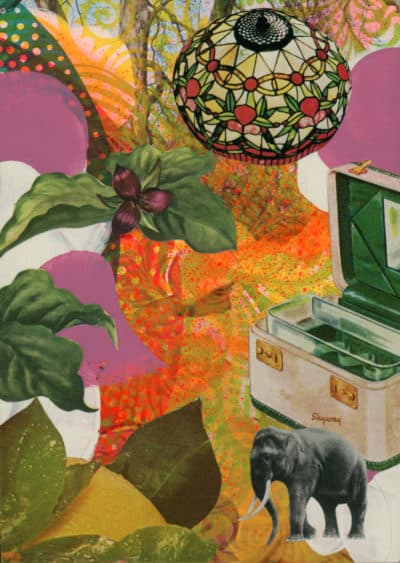

“Part of what was exciting for me personally in this collaboration was not necessarily working together, as in being in the same room working together on a piece, but working on something and then handing it off and not knowing what was going to be happening to that piece of art when it was in Mary’s hands,” says Popinchalk, who herself collaborated on work for the show with Lewey. Popinchalk makes screen prints while Lewey’s medium of choice involves collage.

“It was cool to see what she had done,” says Lewey, who adds that some changes were additions she would never have thought of. “There were more fun colors.”

Advertisement

Twelve pairs of artists were given instructions to choose another artist with whom they might become “pen pals.” The artists were asked to work on several pieces before handing them over to a collaborator who would continue work on the piece (either enhancing or destroying it, depending on the artists’ perspective) before returning the piece to the co-creator. Lewy and Popinchalk requested that the collaborating pairs pass their works back and forth several times before deeming a piece finished. When conceiving the show, they made sure to include artists from diverse mediums. Tim Hansen, for example, specializes in enamel. Conny Goelz Schmitt, his collaborator for the show, creates collage and sculpture. Cicely Carew makes monotypes while her partner for the show, Tolani Lawrence-Lightfoot, currently focuses on floral design.

“As John explained, he and I arrived at these ideas through a months-long process of sending each other art objects, images, and ideas,” says Reison. “For me, at least, it took time and some trials and errors to figure out how this collaboration could both align with my practice and also push me and my work forward in productive ways. This is also what was exciting — the process pushed us each out of our comfort zones and forced us to figure out how we could effectively say something meaningful together, as well as individually.”

So, what happens when artists are forced to reckon with creative forces beyond the walls of their own studios? For one, they can often bond with an artist who holds a very similar working style.

For instance, Roxbury-based French-American artist Cyrille Conan and Japanese-born Boston artist Kenji Nakayama have similar aesthetics. Conan, who has a “day job” as a preparator in the design department at the Museum of Fine Arts, often begins a piece using abstracted text, or with recycled materials he picks up at work. He works with text until it becomes illegible and adds geometric forms to create pulsing, energetic paintings. Nakayama is a street artist and trained sign painter who makes handmade lettering in his South Boston studio.

“I think the value to me was to open a dialogue about our process,” says Conan. “After several studio visits, we realized that our process in making art was similar. We both work on many pieces at the same time and we both have day jobs that infiltrate our practice. Also, our approach is the same. We both rely on intuition and chance.”

“I guess it's sort of like free-form jazz improvisation,” says Nakayama. “I get to have opportunities to do things differently and think differently, sometimes discover new things through the process. And that’s all valuable experiences for us as artists.”

Beverly artist Conny Goelz Schmitt creates sculptures and collages out of vintage books. She took part in an unlikely collaboration with Tim Hansen, creative director and co-owner of Digs Enameling Studio in Lynn.

“I was very hesitant in the beginning since it makes me uneasy to give up control over my work and I don't really like to mix media,” she says. “To me, it seemed a very far-fetched idea to mix enamel and vintage book parts. But it has been, in so many ways, an enriching and eye-opening experience. Sure, I was worried what would be done to my sculptures, but Tim came up with ideas that did not ’destroy’ anything or mess with my ideas but developed them in a direction that I really loved.”

Hansen concurs and adds that he hopes for future collaborations.

“We respected each other’s work, so when we started working on pieces together it just seemed natural when our worlds intersected,” he says

Cicely Carew, a Cambridge artist currently pursuing an MFA in visual arts at Lesley, worked on a series of digital collages derived from her monotype prints and the floral arrangements of Philadelphia artist and florist Tolani Lawrence-Lightfoot. Though the two artists live in two different cities, they found the computer makes collaboration easier. By using a shared Google folder, both were able to give input about how a piece should look.

“Critique was never personal and never an issue,” says Carew.

In the case of the Skibo-Reison collaboration, exciting ideas began to emerge out of that first disco ball dish towel related to current events and civic discourse.

“Chloe made a piece with plastic shrink wrap with an armature underneath,” says Skibo. “That got me to thinking about the civic discourse around the monuments that have been covered and how an object can represent opposite ideas at the same time. So, as of late, we've been talking about Civil War monuments, the act of defacing something, or covering it up, protest and the weight of objects literally and metaphorically.”

Taking part in the show has made opening the mail a lot more fun, says Skibo.

“When I get a package from Chloe, I feel like a little kid again. It's exciting to figure out a way to respond to the unexpected things she sends me.”

“Dear So-and-So” runs Nov. 25-Dec. 29 at the Distillery Gallery with a reception on Dec. 7 from 7 to 10 p.m.