Advertisement

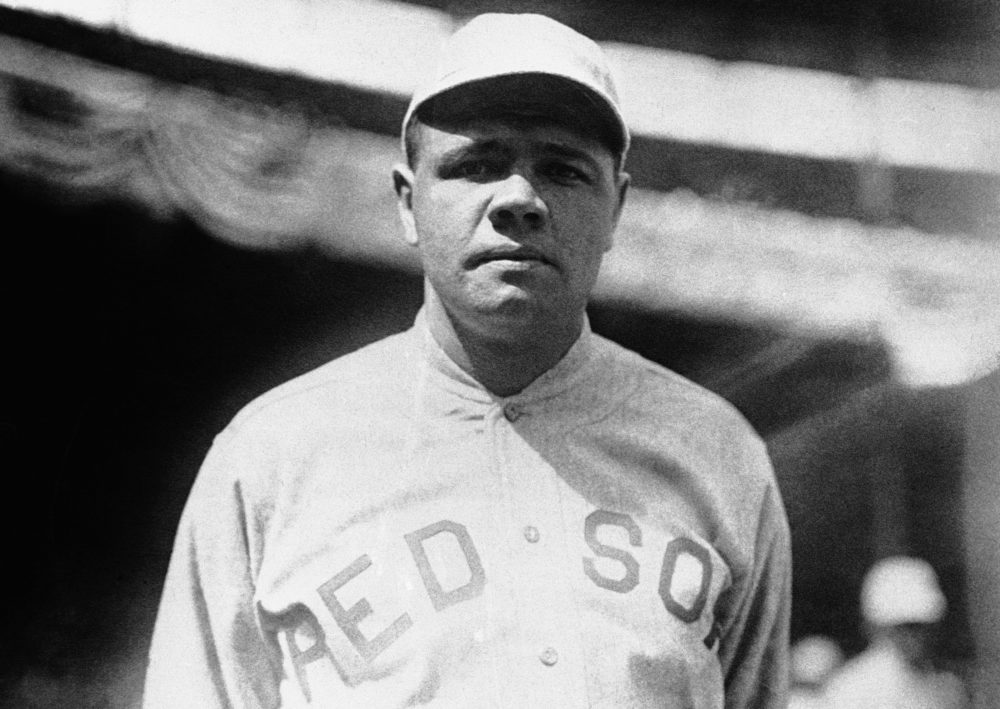

Trying To Make Sense Of The Infamous Babe Ruth Deal, A Century Later

At the scene of the crime, Fenway Park, a sad reminder hangs on a wall.

It's the front page of the Boston Daily Globe, framed and hanging on the office wall of Red Sox historian Gordon Edes. The headline blares: "Red Sox sell Ruth for $100,000 cash."

"I love the [sub] headline underneath it," Edes said. "'Demon slugger of American League, who made 29 home runs last season, goes to New York Yankees.'"

Thursday is the 100th anniversary of a deal that sports fans widely regard as the worst of all time. On the day after Christmas in 1919, the Red Sox sold Babe Ruth's playing rights to the Yankees.

You know what happened next: Ruth hit record numbers of home runs and led New York to four World Series titles. Meanwhile, Boston suffered without a championship for more than 80 years under the "Curse of the Bambino."

In hindsight, we know the Sox made a terrible mistake. But, at the time, the move appeared to make some sense.

There were two editions of the Globe back then. For the evening paper, a reporter collected fans' reactions. Some hated the deal, but others applauded Sox owner Harry Frazee.

"I agree with Frazee," said one. "He knows his business best."

Another asserted that, "star ball players do not make a winning team."

"I admire Frazee's willingness to incur the enmity of the fans, at least temporarily, in his efforts to produce a happy, winning team," said a third.

How could the Sox and these fans have been so wrong? Ruth was already a great player and just entering his prime.

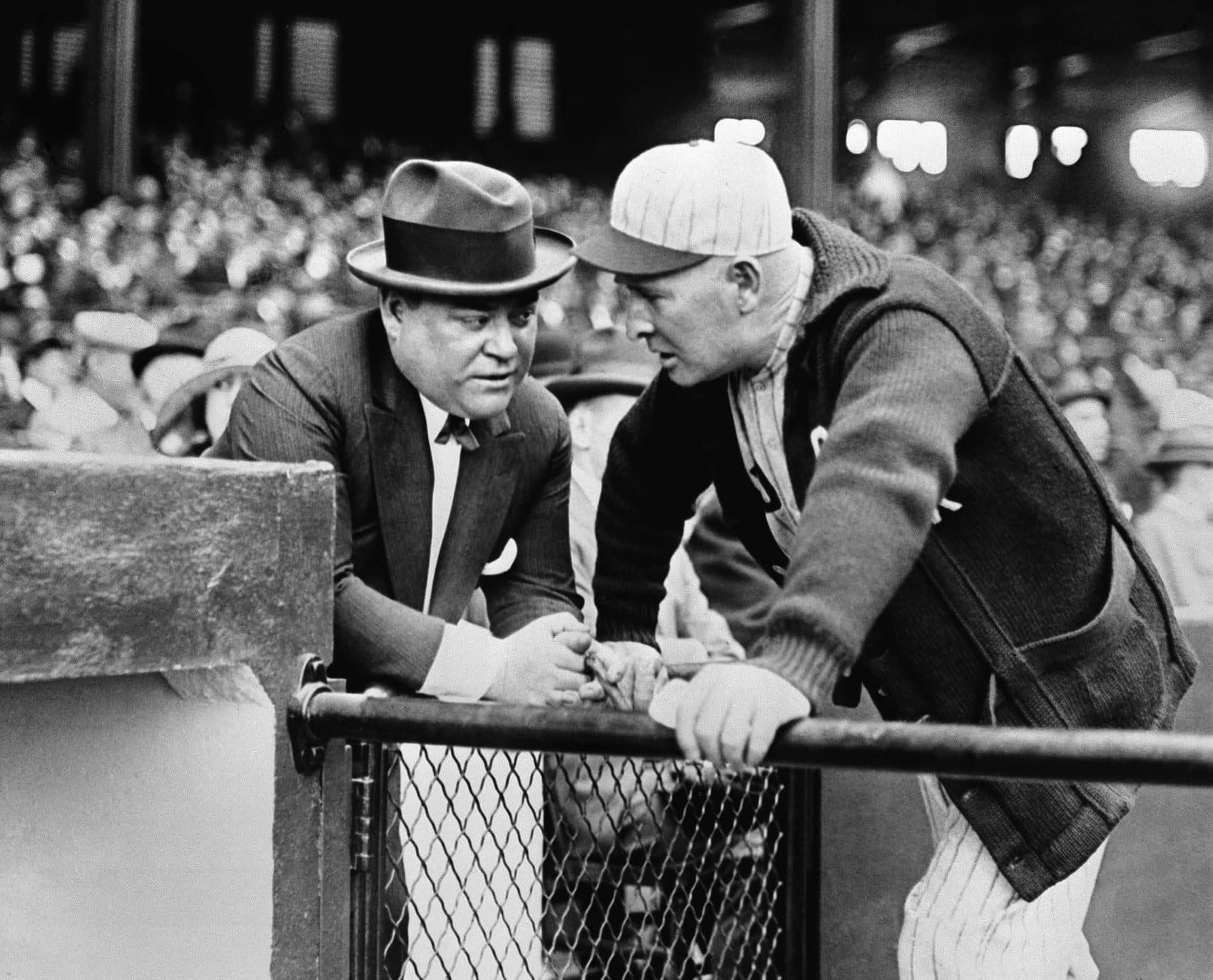

"But he was a handful," said Dan Shaughnessy, Boston Globe sports columnist and author of "The Curse of the Bambino." "By all accounts, he’s kind of a booze bag, and he’s a party guy. He’s definitely a carouser. There’s a car accident downtown, and the woman in the car is not Mrs. Ruth. He’s doing these barnstorming tours, off on his own. He’s not at spring training on time. He’s gaining weight. Just kind of a reckless guy."

Advertisement

So Babe Ruth wasn't exactly a model employee. But those home runs! Maybe the Red Sox could have worked with him on some kind of behavioral improvement plan, said Anissa Zabriskie, a board member at the Massachusetts State Council of the Society for Human Resource Management.

Even if Ruth had cleaned up his act, however, Zabriskie isn't convinced he would have been as good for the Red Sox as he became for the Yankees. She said in sports, as in business, some employees just need a change.

"Sometimes, they're moved to a different role, different position, different company, different company culture where those leaders can get different results from them," Zabriskie said.

Ruth had mostly been a pitcher in Boston. The Yankees converted him to a full-time outfielder, which gave him more chances to hit.

Perhaps the Sox should have had the wisdom to do the same. But consider this: Some of those home runs Ruth hit in New York wouldn't have cleared the fence in Fenway Park's deeper outfield.

And Shaughnessy pointed out that something else happened just as Ruth left Boston: "The end of the dead ball era, the change in the baseball, the fact that the owners figured out, 'Hey, fans like it when the ball goes over the fence. This is exciting.'"

In the dead ball era, pitchers could manipulate the ball with spit or mud, making it hard to hit very far. The practice was mostly banned between Ruth's final season in Boston and his first in New York. The material inside the ball changed, too. Some players nicknamed the new version "rabbit ball" because they thought it was livelier.

In short, the game changed.

"Up until then, baseball was run by micromanagers in the dugout who moved men around the bases like chess pieces," said Ruth biographer Jane Leavy, author of "The Big Fella." "Babe Ruth looks at this and goes, 'Why should I do that, when with one swing of my bat, I can end this?'"

Ruth's home run total jumped from 29 with the Sox in 1919, to 54 with the Yankees in 1920.

In the Sox's defense, it would have been hard to predict, when they let Ruth go, that multiple factors would combine to turn him into arguably the best baseball player ever.

By now, the curse has been broken four times over, and the Sox have learned their lesson.

Or have they?

Back in Edes' office, as the ignominious anniversary approached, the Red Sox's historian considered the frightening possibility that history could repeat itself a century later.

"We have a generational player in Mookie Betts, who's already been an MVP runner-up once, and is annually an all-star, and is just entering the prime of his career," said Edes. "God forbid if the guy ended up in pinstripes!"

Some baseball experts think he could end up in Yankee pinstripes through free agency or even a trade. Betts is under contract with the Red Sox for just one more season.

If he does go to New York, Sox fans just have to hope the 100th anniversary of his departure isn't as full of regret as Babe Ruth's.

This segment aired on December 26, 2019.