Advertisement

Lost No More, Horace B. Jenkins' 1982 Romantic Drama 'Cane River' Screens At The MFA

I’ll never forget hearing it suggested that part of the reason for the runaway success of Spike Lee’s 1986 debut “She’s Gotta Have It” was because audiences had gone years without seeing a black couple kiss in a major motion picture. As part of a demographic that’s pandered to on a 24/7 basis, it was simply impossible for me to imagine not seeing yourself represented here, there and everywhere you look. But indeed the 1980s were a terrible drought for big-screen depictions of African American life, with scarce opportunities in front of or behind the camera before Spike came along and kicked down the doors for a new generation.

One can’t help but wonder what might have been had things worked out a little differently for “Cane River.” The 1982 romantic drama was the first and only feature directed by Horace B. Jenkins, an Emmy-winning documentarian and public television director whose credits included “Tony Brown’s Journal” and “Sesame Street.” Independently bankrolled by a wealthy Louisiana family of mortuary owners, the film was made with an all-black cast and crew, most of them working in their positions for the first time. The story goes that Richard Pryor had attended the New Orleans gala premiere in disguise, with the intention of buying the movie and bringing it to Warner Bros., but he couldn’t reach a deal with the financers. Days later, Jenkins was dead from a heart attack and the film thought lost forever.

Cut to 32 years later, when the negative was discovered — along with prints and elements from hundreds of other orphaned pictures — at the recently decommissioned DuArt film lab in New York City. Thanks to the considerable rescue efforts of Sandra Schulberg’s IndieCollect and a host of other film foundations, a 4K digital restoration of “Cane River” is screening at the Museum of Fine Arts for the next two weeks. Like the recent rediscovery of Kathleen Collins’ “Losing Ground” — also from 1982 — it’s a vital artifact from a lost part of film history, a tantalizing glimpse of a nascent black independent cinema movement that almost was.

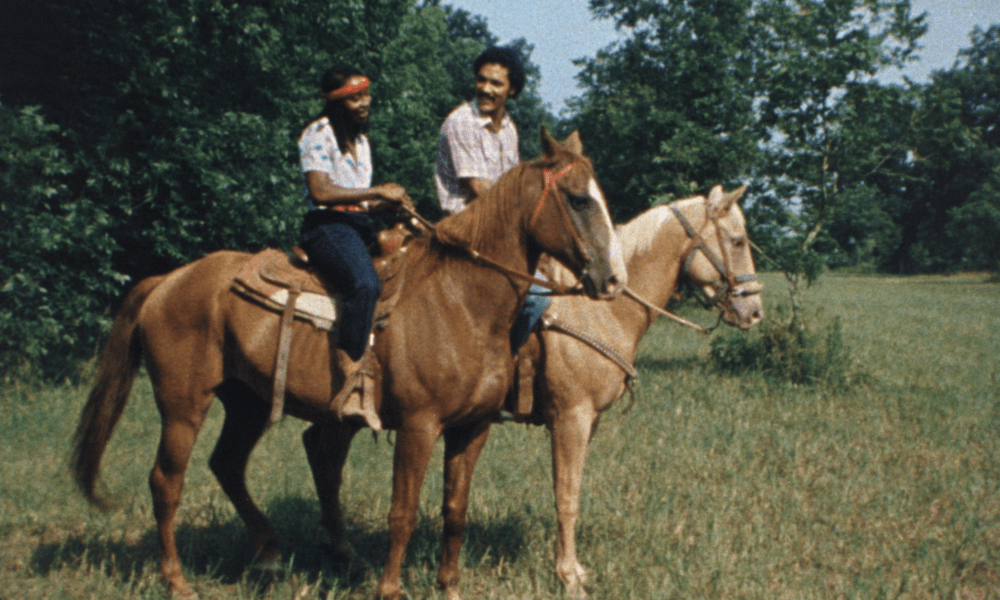

This low-key charmer stars the strapping Richard Romain as Peter Metoyer, a college football star returning to his hometown of Cane River, “a free community of color” in Louisiana’s Natchitoches Parish. Peter was scouted by the pros but turned down an offer from the Jets, uncomfortable with a recruitment process that made him feel like he was on an auction block. He’s come home instead to work the family farm, ride horses and write poetry. (The scribblings we see in Peter’s notebook appear on the soundtrack as sexytime ballads sung by Phillip Manuel.)

It’s on a visit to an old plantation owned by his ancestors that Peter meets Maria Mathis (Tommye Myrick) a spiky, 22-year-old tour guide who will soon be off to college herself, having spent the four years since high school scraping together tuition. Their chemistry is immediate and affectionate, but the blossoming romance is nearly undone by old grudges and historical tensions. The light-skinned Peter is from a well-off family of Catholic Creoles, freed slaves who once collaborated with the Confederacy and still today don’t mingle much with poorer, darker-skinned Baptists from the other side of town like Maria.

The plot outline of “Cane River” almost sounds something like a Hallmark Channel movie (or it would if they ever allowed any people of color in those things) as our well-to-do gentleman returns from the big city to his hometown and promptly falls in love with a girl from the wrong side of the tracks. There’s a gentle, loping rhythm to their courtship, with lots of long, sun-dappled walks, picnics and horseback rides scored by a lullaby harmonica theme from composer Roy Glover. It’s a film full of pleasant, old-fashioned chivalry — Maria can’t stand it when Peter curses — but there are also some cutting, surprisingly contemporary conflicts in their conversations.

However romantic their settings, these discussions ultimately all revolve around the weight of history, and how things that happened 200 years ago still impact us today. To that end, the film pointedly presents Maria’s older brother — angry, hard-drinking former football rival of Peter’s who spends his days working at the local hatchery to put his sister through college and his evenings getting soused into oblivion. It’s easy to see him as a shadow figure of our poet protagonist, the man Peter might have become were he not born into his family’s advantages.

“Cane River” has a clunky, amateurish charm. With its stiff blocking and technical blunders, this is clearly a film by first-timers, and contemporary audiences accustomed to the smoothness of digital production might need to adjust expectations a bit for how massively unwieldy independent filmmaking was back in the 35mm era. Yet the occasional awkward edits and misframed angles lend the picture a DIY authenticity, complementing the earnestness of Jenkins’ love story, and his questions about legacy and reparations that still resonate today. We can only imagine how they would have reverberated back in 1982.

“Cane River” runs at the Museum of Fine Arts from Wednesday, March 4 through Thursday, March 19.