Advertisement

Not Always An Exam School: The History Of Admissions At Boston's Elite High Schools

Boston's search for a new exam school admissions test is the latest in the district's efforts to ensure the city's top high schools — particularly Boston Latin School — reflect the rest of the city. School leaders face mounting criticism over significant demographic disparities at the district's most prestigious schools.

The question of how to make selective high schools more representative of a school district's diversity isn't unique to the city of Boston. Several cities around the country have struggled with the process, too, such as New York City. In the summer of 2018, Mayor Bill de Blasio's proposal to do away with the entrance exam system drew fierce criticism and backlash from alumni and parents who warned of a decrease in academic quality and possible discrimination against Asian students. His administration has since dropped the proposal.

For Boston, the struggle to achieve racial parity with the rest of the district goes back decades. In the beginning, the entrance exam was used to make the admissions process more objective.

Before 1963, getting into Boston's exam schools didn't require an exam at all, just a recommendation from your elementary school principal and good grades. When demand got too high, the district started using more objective criteria like scores on a homegrown achievement test. For minority students, that change didn't make much of a difference in acceptance. In 1971, black students made up just 1.9% of the student body at Boston Latin School. District wide, about 32% of the district's student population was black.

A System Of Set-Asides

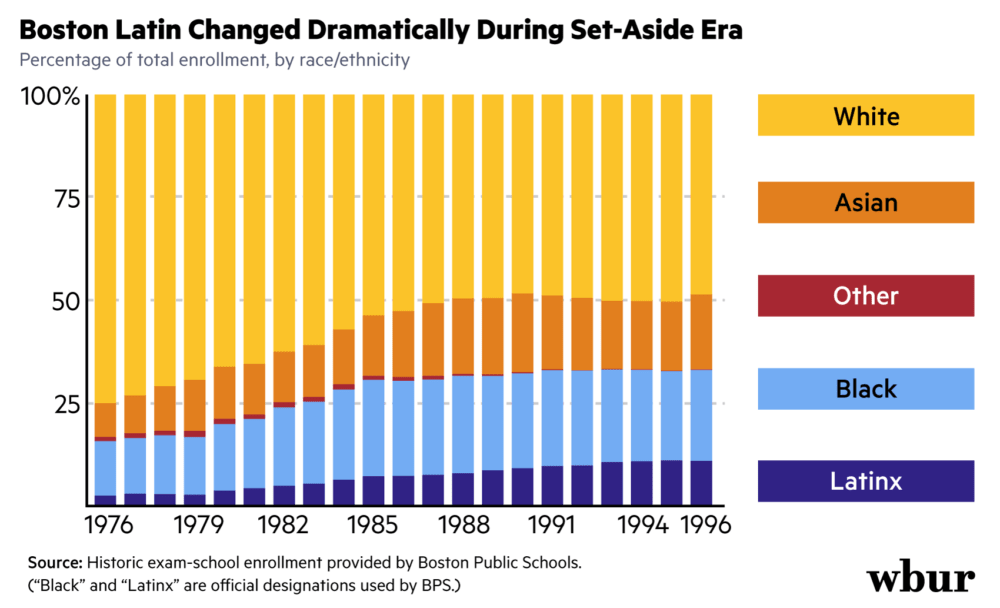

The first dramatic shift in the demographic makeup of Boston Latin's classes would come about a decade later. In 1974, Judge W. Arthur Garrity found in Morgan v. Hennigan that Boston Public Schools were intentionally segregated. Subsequently, Garrity instituted an elaborate and controversial busing plan starting in the fall of 1975. For the exam schools, Garrity ordered a set-aside system that required those schools to reserve 35% of their seats for underrepresented minority students.

"The exam school piece was just part of the bigger picture," said Barbara Fields, a member of the Black Educators Alliance of Massachusetts. Fields is retired now, but she was an elementary school teacher in 1975. "The focus in my community was more on the very tragic things that were happening, like buses being stoned."

But she said black families soon began to notice the impact that exam school policy could have. "[The policy] provided access to schools that were considered to be the best," said Fields. "The populations of people who had been denied access to them for many, many years were very pleased that now their children would have the opportunity."

Advertisement

The set-aside system stayed in place for more than 20 years. And it appeared to work. By 1994, black and Latino students made up 22.8% and 10.4% of the student population, respectively, at Boston Latin School. While still lower than black and Latino representation districtwide, which was closer to 47% and 23%, it was a dramatic increase from the 1960s and early 1970s. (Note: During this time, the district used Hispanic as an official designation, instead of Latinx, which officials use today.)

"Was [the transition] tumultuous? At first, yes," said Michael Contompasis Boston Latin School's headmaster from 1976 to 1998. "But over time it worked to the advantage of all three exam schools."

The set-aside system was also supported by the Boston Latin School Alumni Association and the Boston School Committee, who voted to continue the policy after the court approved plan ended in 1989.

But set-asides were a huge point of contention for some parents. By the mid 1990s, one of them, Michael McLaughlin, who was white, sued on behalf of his daughter Julia, arguing the policy was unconstitutional. Once again, Judge Garrity played a critical role in the policy changes that would follow. He ruled that the policy was no longer "narrowly enough tailored to pass constitutional muster" two decades later. In response, the school committee formed a task force to explore other types of admission plans for the three exam schools. Their solution was a different type of set aside system that used "flexible racial guidelines" for half of the incoming class, which went into effect in 1997. Those changes were concerning for some members of the task force.

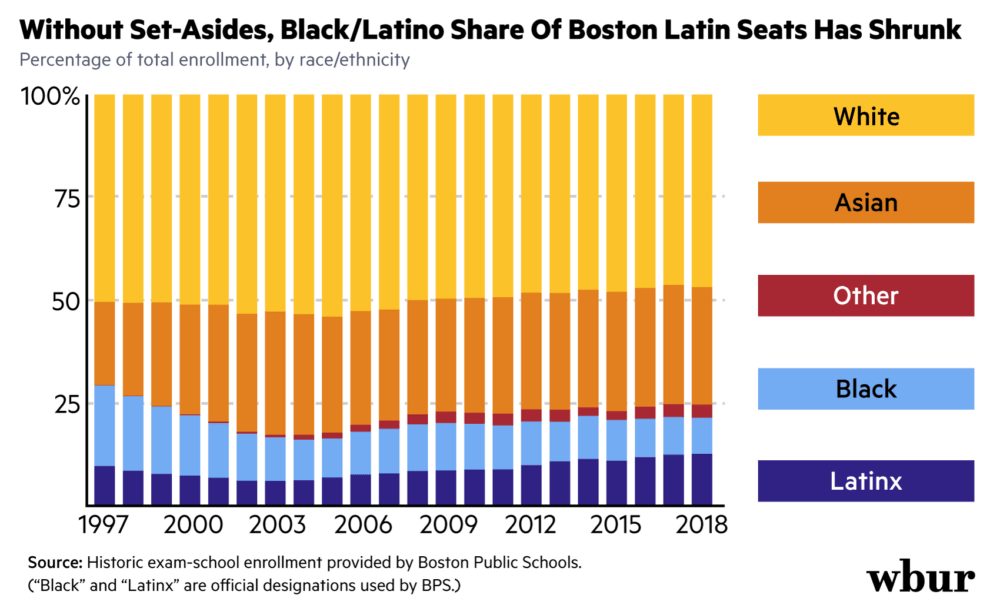

"A number of us were raising the issue about denying black and brown children access to the exam schools if they took away the set aside, which was the only sure thing that would keep the diverse student body," said Nora Toney, a member of a special task force the committee appointed to examine admissions policy options in the 1990s and long time BPS educator. "We predicted that the numbers would go down" if the set-asides were eliminated.

No Consideration Of Race

The final legal challenge against race-based set asides, Wessmann v. Gittens, made it to the First Circuit Court of Appeals in 1998, which ruled in favor of the plaintiff. The school committee decided not to appeal and eventually voted to remove any consideration of race in exam school admissions.

And just as Toney predicted, the numbers of black and Latino students attending exam schools did go down. In 1998, about 19.4% of BLS's student body was black and 9.6% was Latino. By 2005, those percentages dropped significantly to 9.4% and 6.7% respectively.

In an effort to improve minority representation, a group of exam school alumni started what would become the next chapter in the district's diversity efforts, creating and running the Exam School Initiative in the early 2000s. It was essentially a free test prep program aimed at black and Latino students.

At first, the program did show some mild signs of success. In the 2006 school year, the downward trend reversed slightly. Black and Latino populations grew by a few percentage points a year until 2011. But when program leaders moved away from prioritizing underrepresented minorities and opened the programming up to become first come, first served, the numbers of black students attending Boston Latin School dropped again. In 2018, the number of black students attending Boston Latin School dropped to 7.5%, its lowest point in decades.

"There was a point where there were zero schools in Roxbury, zero in Mattapan, and maybe one or two schools in Dorchester that had more than one student in the [Exam School Initiative]," said Colin Rose, the assistant superintendent at Boston's Office of Opportunity Gaps. He felt an approach based on who signed up first and relied on parents being in the know was making opportunity gaps for black and Latino students worse.

In 2016, the district took control of the Exam School Initiative. Since then, officials like Rose have tried to revive the free test-prep program.

"How do you give a fairer chance to the folks who aren't privileged and can't pay $3,000 to prepare for a test," said Rose, referencing the costs often associated with private courses.

In the last four years, his team has taken several steps to improve participation by underrepresented minorities like adding more than 300 slots, creating advertising about the program, and offering free transportation to weekend test prep programs.

Rose described the programming as more of an attempt to mitigate inequities. "Over the last 4 years that I've been in [BPS's] central office there's been a lot of conversation around the exam school test in particular and the fact that it doesn't necessarily align to the things that students are doing in our schools," he said. "No matter how brilliant you are, if you haven't been exposed to content, if you haven't been exposed to the beans of a test, its like walking in to the bar exam cold," he said.

Former BPS educator Barbara Fields sees these efforts as at least a step toward equity. But she argued, it's merely a Band-Aid on a broken system. "Maybe the the major question is 'Should there even be a test?'" she said.

But doing away with an entrance exam doesn't seem to be an option on the table — at least not in the near future. "I'm not going to get rid of the test. It's an exam school. That's that's what it's always been," Mayor Marty Walsh told WBUR's Tiziana Dearing in an interview last week.

Still many education advocates contend the district should be doing more to improve access to its prestigious exam schools. Groups like Lawyers for Civil Rights and the Boston branch of the NAACP argue there are several options that pass constitutional muster that BPS officials could be exploring such as reserving seats for the highest ranked students in each zip code or instituting a more holistic admissions model — similar to what college admissions officers use — where race can be a factor as long as it's not a deciding factor.

"The Supreme Court has implied that the standards are essentially the same between the way the admission system would be viewed for higher education and the K-12 context," explained Oren Sellstrom, the litigation director at Lawyers for Civil Rights. But he stressed the laws that govern school admissions go both ways when it comes to race. While schools can't consider race too heavily, districts are also obligated to find an admissions system that doesn't have a disparate impact on students of color.

"If the district continues to rely on a standardized test that not only doesn’t measure what students are currently learning and the test maker itself has said is being misused by the district, then the district is going to be at serious risk of facing a legal challenge from students that are unfairly excluded from that process," said Sellstrom.

In a statement, Superintendent Brenda Cassellius said the current request for proposals from test makers is the next step in efforts to increase diversity.

"Our goal is to use an open and transparent process to identify a high-quality entrance exam demonstrated to be free of bias and aligned to Massachusetts state learning standards," she said.

After that, BPS said it would continue to evaluate other options to increase representation of black and Latino students at the exam schools. City and school leadership have also stressed that exam school access is only part of the equity equation in the district.

"I think we spent so much time focusing on the three exam schools and not really focusing enough on the other schools," said Walsh. "And part of our reorganization, our high school redesign, is to pull our other high schools up so there are options for parents."

This segment aired on March 5, 2020.