Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

Bringing Home Something Deadly: How Health Workers Are Isolating From Their Families

In Italy, roughly 20% of those infected with the coronavirus work in health care. While we don’t have those numbers yet for Massachusetts, there are at least 700 hospital employees who have tested positive - and that doesn’t include all hospitals. Many of these health workers fear that they might inadvertently carry the virus home, infecting their family members and neighbors.

Because supplies of masks, eye protection and face shields are limited, health care workers must resort to dangerous rationing measures like reusing potentially contaminated masks. There’s a near universal call for more masks and other gear to help prevent the spread of the virus within hospitals.

Employees of Massachusetts hospitals are going to great lengths to avoid infecting family members and roommates. Front line staff are borrowing camper vans, sealing off sections of their apartments with plastic, and listening to birthday celebrations from the isolation of a basement room.

We asked a few clinicians to share their experiences. We summarize them below. You can also listen to edited versions of their audio dairies. Thanks to everyone who contributed to this report and to all who keep going to work during the pandemic.

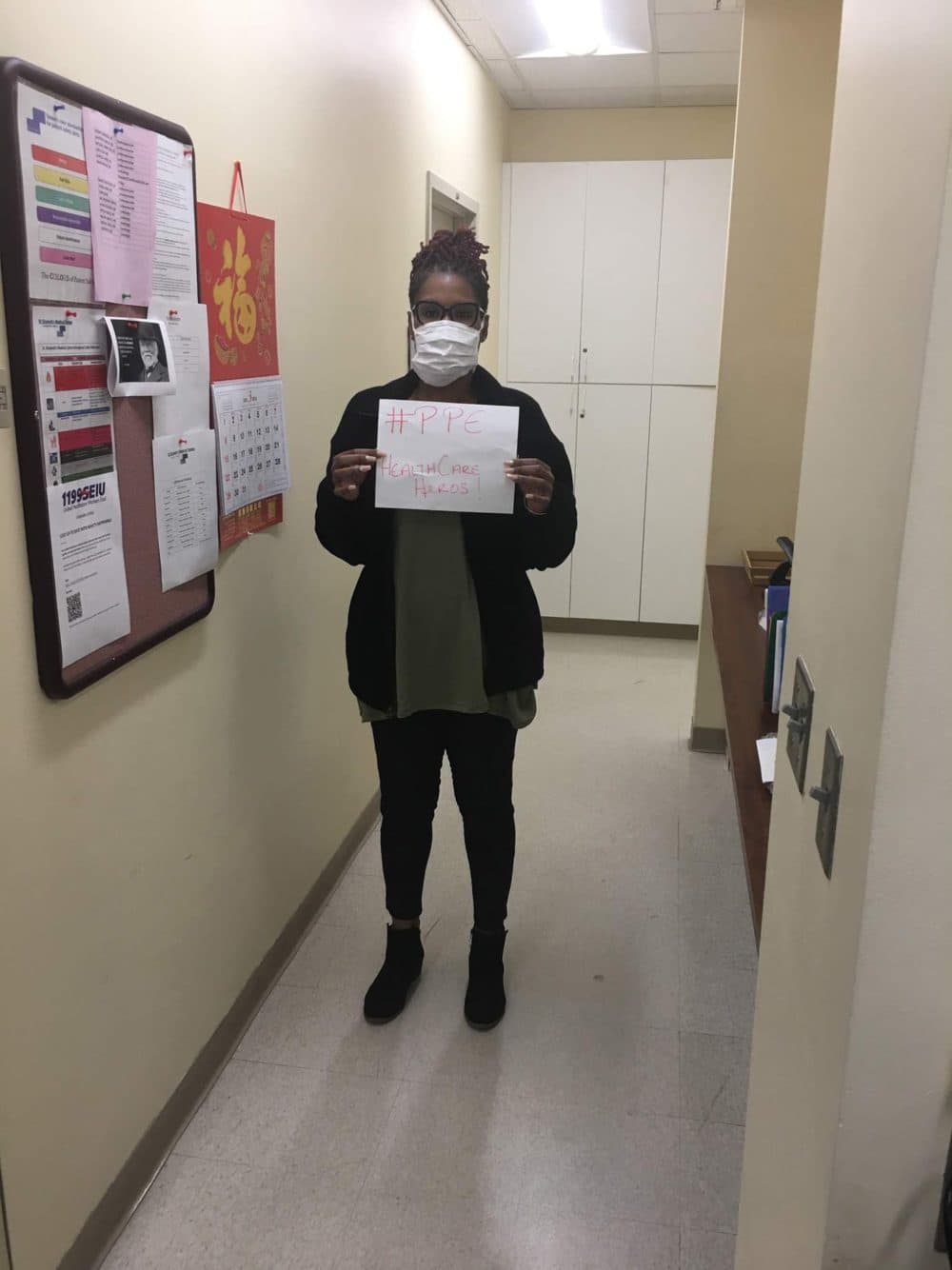

Alyssa Bartholomew, lead patient access coordinator at a Boston hospital

Bartholomew looks forward to picking up her 6-year-old daughter from daycare every day after work and giving her a hug. But right now the hugs have to wait until after mom, wearing gloves, has stripped both of them and sent her daughter into the shower. She tries to disinfect everything and mop before her daughter comes out of the shower.

“So she hasn’t seen that part of it,” Bartholomew said, “ because I don’t want to put so much panic on her that she can’t comprehend why.”

Josh Merson, emergency medicine physician assistant from Chelsea

Merson is 33 years old. He takes a number of steps to avoid infecting his 18-month-old son and his wife, who has asthma. When returning from the hospital, Merson enters the family’s condo as if he’s entering a hazmat containment zone.

“Everything outside is hot, any transition area is warm and must be cleaned. After I get out of the shower everything I touch is cold or considered safe.”

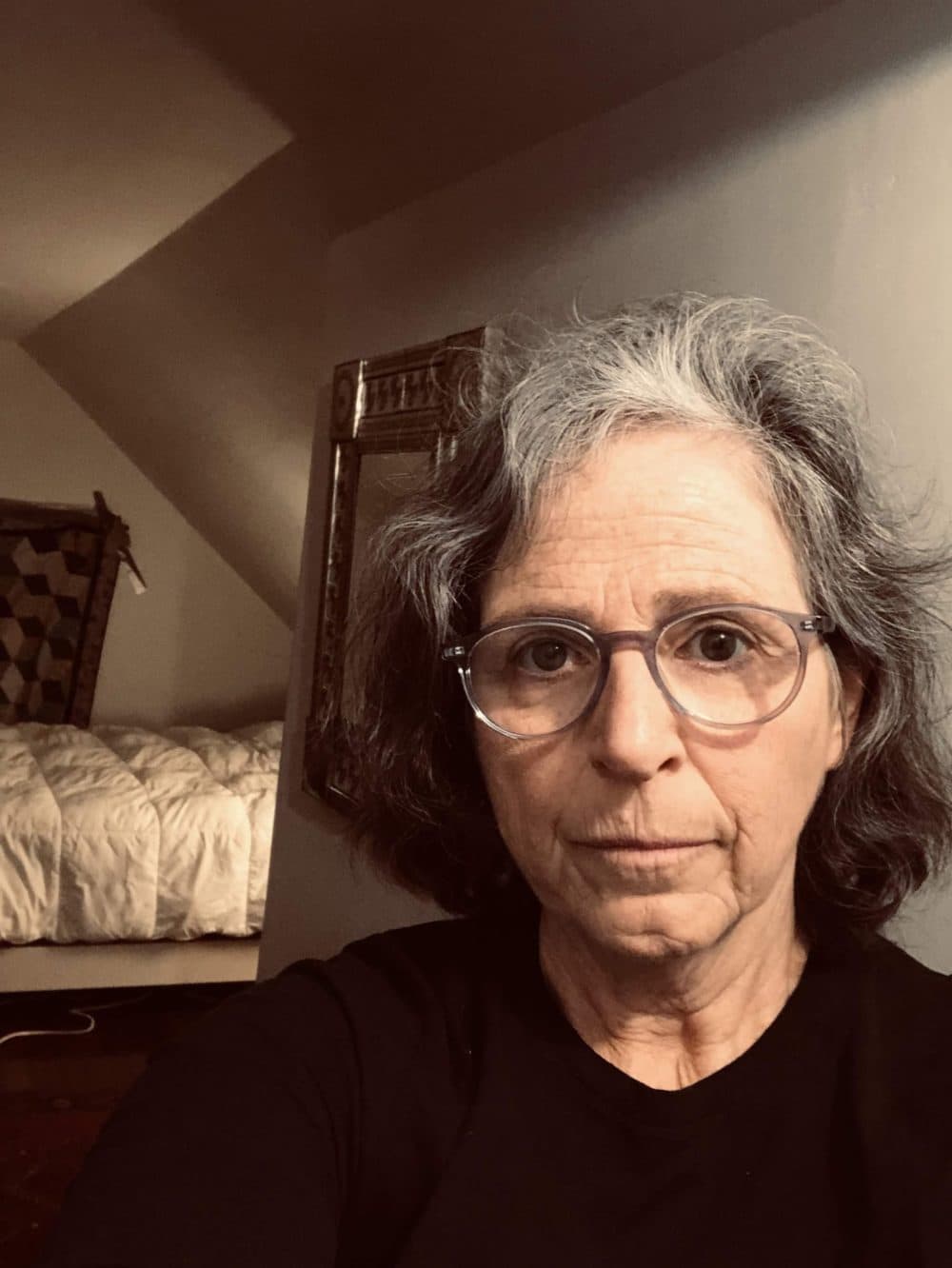

Elizabeth Mitchell, emergency room physician from Boston

Mitchell has moved into an attic bedroom to be away from her family. She transfers everything she needs to and from work in ziplock bags, including her phone, ID badge and clothes. Everyone in her home uses individual soap, towels, toothpaste. There is no sharing of food.

“It’s pretty stressful and it’s a lot of work, but I hope it helps keep everybody from getting sick.”

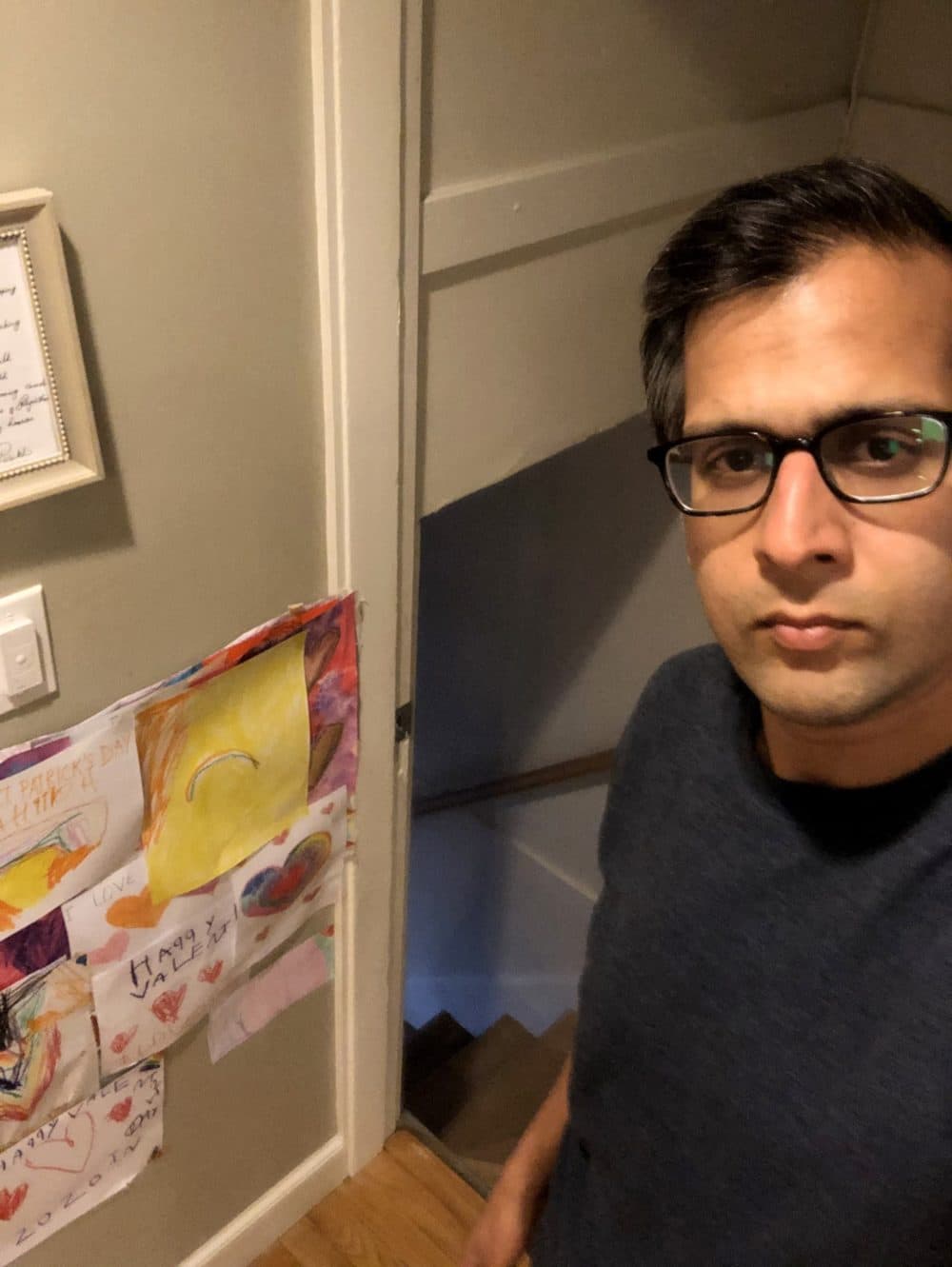

Mihir Parikh, physician specializing in lung diseases

Parikh, who is 39, has two daughters. He lives in Newton with his children and his wife, who became infected with the coronavirus. For two weeks, his wife moved to a basement bedroom where she took her meals.

“Our daughters are young,” he said. “It was really, really tough to tell them, ‘yeah, mommy’s downstairs but you can’t see her, you can’t really talk to her, you certainly can’t hug her or snuggle with her.’ ”

Jennifer Roach, labor and delivery nurse in Boston

After an exposure to COVID-19 at work gave her and her husband a scare, the couple divided their apartment in half. She comes up the back stairs and “lives” in the bedroom. He comes in the front door and uses the living room and kitchen. They share the bathroom, with lots of bleach.

“We have chairs eight-feet apart from each other in the hallway so we can hang out sometimes between my work shifts.”

Jairo Suarez, medical interpreter from Worcester

Suarez, who is 58, lives with his wife, 16-year-old daughter and 82-year-old mother-in-law. He’s especially worried about infecting her. When he gets home, he uses bleach wipes to disinfect his car, keys, phone and backpack. He wears the same coat and shoes every day and leaves these in the car. He undresses in the garage, puts all his clothes into a plastic bag, and heads straight for the shower.

“I do not want to be sick, and I don’t want to make other people sick,” he said, “including the patients I see.”

Gabe Tash, emergency room physician assistant

Tash brings a bag with multiple sets of clothes from his home in Andover to work each day. After his shift, he washes and changes clothes at the hospital. He disinfects his phone and badge before heading to his car. He changes shoes there before getting into the vehicle. The work shoes and his work bag stay in the car.

Tash, who is 37, avoids wearing a coat to minimize the articles that must be cleaned daily.

“At the end of a night shift all you want to do is just get in bed and call it quits, but this is a change that’s quite necessary to keep my family and me as safe as can be.”

This segment aired on April 3, 2020.