Advertisement

Unearthing Busted Statues' 'Ashes And Relics' And Boston's Punk Underground

Punk shook the world in 1977. EMI had just dropped the Sex Pistols for saying “f--k” on British television. The Ramones had released two seminal records later that year in New York. The subsequent “success” of punk, if you could call it that, took the music industry by the neck and suffocated the status quo, its anarcho-gospel spreading like wildfire across the United States. Suddenly, New York and London weren’t the only hot spots; regional cities like Minneapolis, Washington, D.C. and Boston had latched on. The spirit of the American youth had caught fire.

Boston was particularly fertile ground for the underground music scene, largely spearheaded by the formation of Mission of Burma. Built from the remains of a group called Moving Parts, Mission of Burma — composed of guitarist Roger Miller, bassist Clint Conley, drummer Peter Prescott, and with the addition of Martin Swope on tape loops later on — were the beacons of the Boston underground. Kurt Cobain was vocal about his admiration of the band. The Boston City Council even decreed Oct. 4 Mission of Burma Day. Their footprint in this city is gargantuan. “It’s hard to overestimate how central they were to that community at that time. They really felt like a sort of bedrock,” former Boston musician Bob Moses tells me.

What Moses is underplaying is his own role in Boston’s underground music history. His former band, art-punk collective Busted Statues, are a missing link in the city’s music mythology. More specifically, Moses has recently unearthed a significant relic from the scene: A Busted Statues EP recorded at the legendary Fort Apache studios in 1988 that ties global punk icons and music industry magnates to the prolific, yet often overlooked history of Boston underground counterculture. “I opened up a couple of 16-track, one-inch reels and discovered Sean Slade’s hieroglyphic track sheets from the original Fort Apache, back when they first started,” he tells me. These sessions, dubbed “Ashes and Relics,” have been restored, remixed, mastered and reissued online.

A young Sean Slade was cutting his teeth in Boston as a local musician and self-taught sound engineer at Fort Apache preceding his success as a top-tier music producer for bands like Radiohead and Hole. But even before he found himself in the high-stakes arena of major label production, Slade remembers territorial chest-puffing around town as the scene became stronger and more broadly recognized, particularly one incident involving a local producer. “He actually kind of attacked me in a club one night,” Slade alleges. “I was just standing there and suddenly some guy came up behind me and grabbed me by the waist and picked me up into the air and I go, ‘What the f--k is going on?’ I turn around and he’s looking at me and says, ‘You stole my band,’” referring, of course, to Busted Statues.

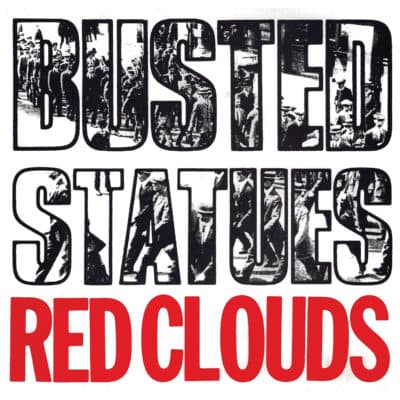

The altercation followed the buzzworthy release of “Red Clouds” in ‘89, the sparky, anthemic lead single from the Busted Statues “Relics” sessions, co-written by Mission of Burma’s Clint Conley during a period of which he had almost entirely retired from music. “I was writing songs — I was really ambivalent about playing music myself — but I had a notebook full of music, and I thought maybe Moses could use it,” Conley recalls. “I remember going over to Moses’ apartment and playing ‘Red Clouds’ for him and recording on a little cassette. I just thought it would be cool if I could write songs and have somebody else sing the damn things and do all the damn work and tour around.”

Moses and Conley have deep ties. Long before the Busted Statues, even before Mission of Burma, the duo met as bartenders at a bar called Jack’s just off of Harvard Square. “It was largely a jock bar, we were mandated to wear rugby shirts,” Conley says begrudgingly. “Bob and I, the two of us were these dweebs. We shared an interest in art and music that was a little different from the rest.” Moses remembers seeing Conley perform with Moving Parts just as punk rock began surfacing in New England. “Like everybody else then, punk rock was very important. It really convinced you that there was something you could participate in,” Moses says.

Meanwhile, as a student at Yale, Sean Slade was getting his lesson in punk rock first hand. “We went to CBGB’s in ‘76 and dropped acid and went to go see Wayne County and Tuff Darts. I was there the night Wayne County attacked Handsome Dick Manitoba with a mic stand. It happened 10 feet in front of me,” he says proudly. “But a lot of us had moved to Boston because it was the coolest place to have a rock band,” he adds.

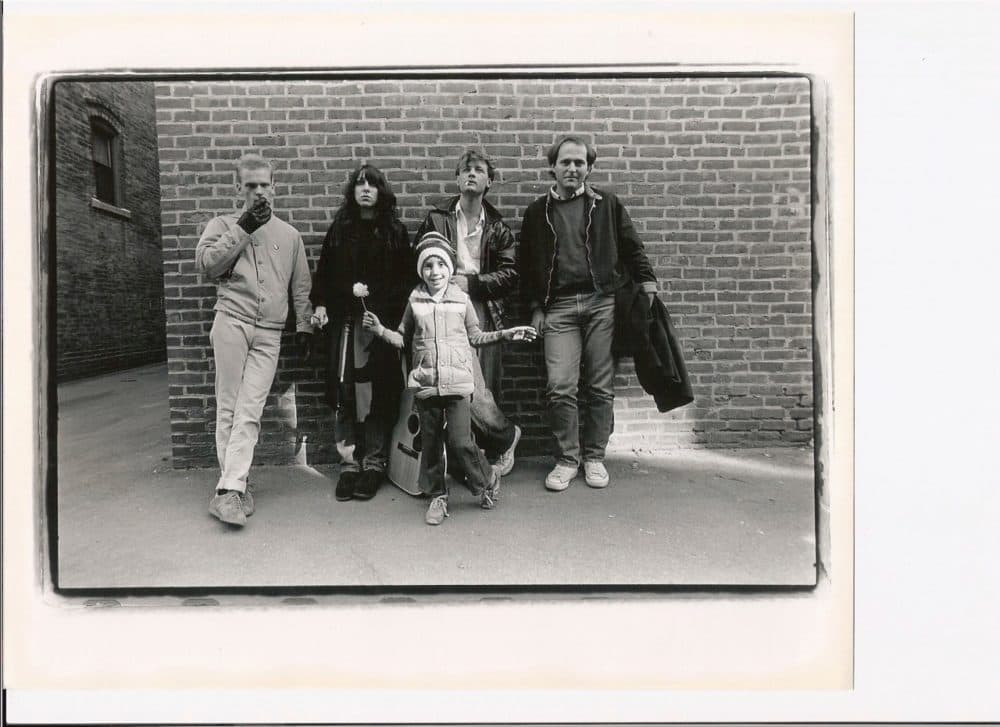

The formation of Busted Statues can be attributed almost entirely to Mission of Burma. Moses would meet his fellow Statues while palling around with Burma before gigs. Statues bass player Diane Bergamasco was a local photographer and girlfriend of Burma drummer Peter Prescott; Moses recalls meeting Statues vocalist Bob L’Heureux and original drummer Michael Mooney on the loading dock of Burma’s rehearsal space. Upon dubbing themselves as Burma “crew members,” the Statues took a stab at songwriting themselves. “You know, the origins of the band was more or less Mission of Burma roadies plus one Mission of Burma girlfriend,” Conley remembers. “So they formed a band and I confess, I thought, ‘Oh, that’s kind of cute.’ But then I heard their music and I was like, ‘Oh my god, this is solid!’”

The innocuous downfall of Burma in 1983 resulted from an unfortunate side effect of the band’s notoriously loud performances; guitarist Roger Miller had developed tinnitus. “Once they were absent from that, there were a lot of people who were pulled into that void, and it was like, ‘Let’s see what we can do,’” Moses says. Burma had inadvertently passed the torch. The Statues grabbed it and ran.

Busted Statues soon found themselves thrown into the electrifying world of Boston’s rock underground, landing supporting shows for bands like Hüsker Dü and The Dream Syndicate, even occasionally brushing up against post-punk royalty Gang of Four. The Boston circuit was swelling. Groups like Big Dipper, Salem 66, Volcano Suns, Bullet LaVolta and The Lemonheads were drawing crowds. The Pixies and Throwing Muses were just getting their start. It was a scene Conley describes as “insular within an insular world, the sort of art-rock underground.”

Fanzines like Conflict were popping up and funding local shows while compilation tapes were passed around with fervor. Matador Records co-founder Gerard Cosloy was just a teenager when he created “Bands That Could Be God” in 1984, a local punk rock compilation that featured Deep Wound (the origins of Dinosaur Jr.). “Let’s Breed,” another local underground compilation record from record label Throbbing Lobster, included “Heart Upside Down,” the Statues’ first single release. But just as the Statues began to enjoy the buzz of local radio play, Moses put the band on hold indefinitely to travel around Asia for a year.

All the while, Sean Slade, along with roommates and Yale compatriots Paul Kolderie and Jim Fitting, were cultivating the initial framework of Fort Apache Studios. “Kolderie found it,” Slade recalls. “He was just wandering around Roxbury and he found this old commercial laundry building. Some crazy guy had bought it and he was determined to turn it into artist loft spaces.” The trio partnered with local musician Joe Harvard to help fund the studio’s recording gear.

“The first year we were teaching ourselves, so each of the partners had his own band come in and we recorded our own bands,” Slade says. “It took us all of 1986 to get our s--t together. By ‘87, we were semiprofessional enough to take on clients and we recorded anyone who booked the time — that’s how you really learn.” Slade recalls that the Pixies’ “The Purple Tape” was recorded shortly before the “Relics” sessions with Busted Statues.

Upon returning to the U.S. in 1987, Moses reformed Busted Statues with the addition of Andrea Parkins and Chad Crumm on accordion and fiddle respectively, an era he described as “a whole other chapter.” Enter the alleged Sean Slade assailant Steve Barry, a spirited hip hop producer around town known as “Mr. Beautiful,” who took the Statues to Q Division to track their next record. “I have no clue what happened to those tapes,” Moses digresses.

The Statues underwent another lineup shift, this time dropping Parkins and Crumm and adding The Five drummer Brian Gillespie and David Kleiler of Volcano Suns on guitar. They booked two sessions at Fort Apache in 1988 with Slade. “They walked in and they seemed like a really cool band,” Slade recalls. “They had this kind of high-IQ art-rock vibe. I was totally drawn to that.”

Both Moses and Slade described the “Relics” sessions as “set up and play.” During the first session, Slade captured the band performing a handful of songs live in the studio with minimal intervention; the second session was for vocal overdubs and mixing. The sessions produced five songs, including two singles — ”Red Clouds” and the trampling new wave B-side “The Bo Tree” — that dwelled in mysticism, apocalyptic fever dreams and the manic energy of 1980s Reagan-era post-punk. “Thematically, in terms of ‘Red Clouds,’ it’s this sort of apocalyptic vision that Bob had. Songs involving monks who appear to save a village from ecological disaster, even a plague song.” The singles were sent to local alternative FM radio stations like WBCN and WMBR and subsequently pressed by Erik Lindgren of Arf! Arf! Records. “Red Clouds” became a hit on the college radio circuit.

And then, radio silence. The “Relics” sessions were passed on to Moses but were shelved and never released.

The Busted Statues’ musical interests began to diverge in the years following their regional success. Distinguished shredder Corey Loog Brennan of The Lemonheads replaced David Kleiler on guitar before the group eventually disbanded in the early ‘90s. Diane Bergamasco dug into the alternative scene with bands like Mindgrinder, eventually auditioning for Hole (she didn’t get the gig). Bob L’Heureux took up country music crooning.

Sean Slade went on to produce Radiohead’s debut album “Pablo Honey” with Paul Kolderie in 1992 and was instrumental in the massive global success of their single “Creep.” He would later produce Hole’s “Live Through This,” as well as recordings by Lou Reed and Weezer. Slade now teaches music production and engineering at Berklee College of Music.

Following the dissolvement of Mission of Burma, Clint Conley put music on hold to pursue a career in broadcast journalism. He came out of retirement twice in the 1980s: once to produce “Ride the Tiger,” the debut album from indie stalwarts Yo La Tengo, and once to help Moses craft “Red Clouds.” He formed a group called Consonant in the early 2000s while periodically reuniting Mission of Burma. He currently works as a producer for WCVB-TV, an ABC affiliate in Boston.

Bob Moses joined a new group called Kustomized that got signed to Matador, but ultimately gave that up after moving to New York City in the mid-’90s; he’s now in artist management with First City Artists.

I asked Moses why it’s important for “Ashes and Relics” to be released 30 years after its conception. “I wish I could tell you that I knew when I found these things that the time would be right, but upon listening to it, I found it really compelling musically and in a way that it sounds fresh to me again,” he says. “At the time, there was — although not nearly to the extent of now — that feeling of danger and apocalypse in the air. It’s all just weirdly relevant.” And so the spirit of punk remains.

Correction: An earlier version of this piece misstated Bob Moses' role with the band Kustomized. He did not start the band, he joined the group.