Advertisement

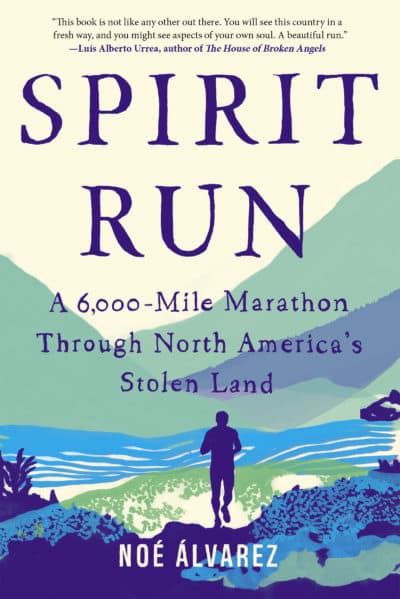

In Memoir 'Spirit Run,' Noé Álvarez Relays An Existential Reckoning

Noé Álvarez was the first person in his family to run on his own terms. As the son of Mexican immigrants who migrated to Yakima, Washington in pursuit of a better life, he grew up with the belief that “running was a bad thing. It was a thing you did to survive.” When Álvarez decided to run the Peace and Dignity Journey (a 6,000-mile marathon created to unite and heal indigenous nations from Chickaloon, Alaska to the Zaculeu ruins in Guatemala), he intended to honor his parents by retracing their journey in reverse. His memoir “Spirit Run” recounts how a grueling ultramarathon offered a powerful spiritual reckoning with his ancestors, the land and himself.

When Whitman College granted Álvarez a full-ride scholarship, it was cause for jubilant celebration for his mother, who worked in fruit processing and distribution centers for decades, and his father, who was an orchard laborer turned carpenter. His father had told him, “It’s college or the fields,” because there were precious few other opportunities in their community. But Álvarez found it difficult to adjust to such high expectations and held himself against negative Latino stereotypes. He fell behind on coursework and continued through his first year in a mental fog. When he attended a student activist conference, he learned about the Peace and Dignity Journey, and Álvarez found clarity about what he needed to do next to make peace with his heritage.

Every four years, representatives in the Peace and Dignity Journey (PDJ) run relay-style between indigenous communities throughout the western hemisphere under a unifying theme as a way of preserving spirituality. The theme of PDJ in 2004 was “women.” (Other years have included “family,” “youth,” “elders,” “reactivate sacred sites” and “water.”) Since anyone who was willing to put in the work was welcome to join the run, regardless of indigenous heritage, Álvarez decided to temporarily drop out of college to join the run and understand his parents better. (His grandfather was of Purépecha descent but Álvarez grew up culturally Mexican.) He knew he had a lot to learn about how the other runners and tribes were plagued by histories of poverty, substance abuse, oil extraction and forced assimilation, so he approached the run humbly and with an open mind.

Álvarez was not a trained runner prior to signing up for the PDJ, and he only had a month to prepare for this ultramarathon that contractually obligated him to run in intervals of 10 miles or more per day. If other runners got injured or dropped out, someone had to make up those additional miles as well. He said his conditioning was really his upbringing, since he was always working, putting hands to the soil in the apple orchards of Selah, Washington. Though the run was physically taxing on the body, Álvarez joked, “running is the easy part.” Getting along with flawed people with broken histories could be challenging under the best of circumstances. However, they all showed up to do the work to better themselves, and Álvarez said they ultimately healed because nature forced them to heal.

Although the runners all had the theme of “women” to set their intentions for the run, each person brought their own reasons and visions for running, and their different backgrounds informed how they adapted to a journey over 4 months and thousands of miles long. The philosophy of the run was deeply rooted in the soil and whatever stories come out of that. They ran through sacred territories, across rivers and up mountains that were the foundations of a given tribe’s origin story for their land-centered religion. “With contamination, deforestation and decimated landscapes, that’s erasing their stories and erasing them as a people,” Álvarez said. When the group reached different tribes who welcomed the run with celebrations, the model of the run would shift to fit the history of their land and their people, as PDJ didn’t seek to impose their own priorities on anyone else.

“With the stories you hear on the run, you forget you’re running all these miles,” Álvarez said. “It’s ecstasy wanting to see the next community. You discover true strength.”

Advertisement

“Spirit Run” could not have been told without the runners. Álvarez chronicles their stories alongside his own. In Lillooet Nation, Zyanya Lonewolf experienced the violence of the Highway of Tears firsthand when cars tried to hit her while she ran in honor of her cousin who was murdered there. Men articulated emotional experiences in ways Álvarez had never heard before. If they could show tears and love, that challenged his belief of what it means to be a man. “There’s truth to relinquishing to the land whatever weather and whatever obstacles are thrown at you,” Álvarez said. “You had to tell yourself why you were running. It’s about committing to something bigger than yourself. It’s your community.”

Álvarez said, “I’m nothing without people, I am nothing without my parents, I am nothing without my community. Their lives continue to inform me and transform me.” He continued, “This was always my parents’ story.” Storytelling in the Álvarez household was always an oral tradition. For “Spirit Run,” he wove together stories he recalled his parents told while he was growing up, but he also sat down with them as an adult to ask about their journeys. “I wish they saw the strength in their story more than they do. It was such a large distance, and not knowing the language, is such a courageous thing. It scares me. I want to honor and embrace that.” But his journey scared his parents too. “For my mom, leaving means forever. People from their hometowns emigrated for new opportunities all the time. I had to be sensitive to that and promise my travel was different.”

“Spirit Run” is a beautiful amalgamation of Álvarez’s part in the PDJ run from the brutal toll it took on his knees, the bonds he forged with other runners (and the arguments that arose), his run-in with a mountain lion — all while harkening back to poignant passages of his parents’ migration story, with thematic connections to the run’s ever-shifting spiritual focus. Unlike most marathons, the PDJ is not about competition or personal records. Álvarez said it’s about finding power in running, and knowing there’s so much more power with other people.

Álvarez intended to join the next Peace and Dignity Journey during the summer of 2020, but the physical run has been canceled due to concerns over COVID-19. Instead, the PDJ’s 2020 theme of “Sacred Fire” will be honored by lighting fires in participants’ homes, pueblos and nations between April 16 through Dec. 21. Since they cannot traverse the distance physical between communities, they will keep the spirit of the fire in their hearts to unite individuals as one.