Advertisement

Dispatches From The Front Lines

Spiritual Care At A Distance, Masked: Chaplains During COVID-19

Hospital and nursing home chaplains are working round the clock, often in circumstances they never imagined, as the death toll from COVID-19 rises in Massachusetts and beyond.

WBUR asked four members of the clergy who counsel patients in COVID-19 units to capture part of this experience.

Rabbi Karen Landy is the senior staff chaplain at NewBridge on the Charles, a senior living community in Dedham. She says her role has changed dramatically with COVID-19.

She’s always been involved in end of life conversations between patients and their families. But now, as patients lay dying, it’s just Landy, covered head to toe in protective gear, and a medical resident in their room. Landy holds an iPad, inside a plastic bag, up to the patient’s face while their spouse, children and grandchildren say goodbye. She can usually manage to hold the iPad steady for about 20 minutes before she has to take a break. She cries through the stories, laughter and final words of peace.

“I am grateful that I have the strength and the experience and the wisdom to be able to hold these moments,” Landy says.

When the conversation ends, Landy sheds the PPE and finds a window where she can look out at the world and regroup. She facilitated four such conversations one day last week. NewBridge staff need extra attention these days as well.

“We are all in this together, holding each other,” Landy says.

Cathy Pimley, supervisor of pastoral care at UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester, says dealing with the pandemic as a spiritual advisor has been surreal and profound.

She says using technology to help patients and loved ones communicate is a difficult way to console people.

“For years as a chaplain, my ministry has been my eyes, my words, my presence, my ability to listen, reaching out a hand, prayer.” Pimley says. “Now all of this has to happen behind a mask which muffles my voice and separates me from others.”

Last week Pimley received a call from a man who asked her to say a prayer for his wife who had died. Having never been to the hospital morgue, Pimley made some calls to figure out how to get there. She blessed the woman’s body with a nurse standing nearby.

“Sometimes with all this going on I can’t cry,” she says, “because I’m afraid if I do it will be a waterfall.”

Despite the unrelenting sadness, Pimley says she’s grateful to do this work.

“I pray that when the pandemic is over and when we begin to heal that my colleagues who have put their lives on the line will be able to breathe, to heal from all that they have witnessed,” Pimley says.

Advertisement

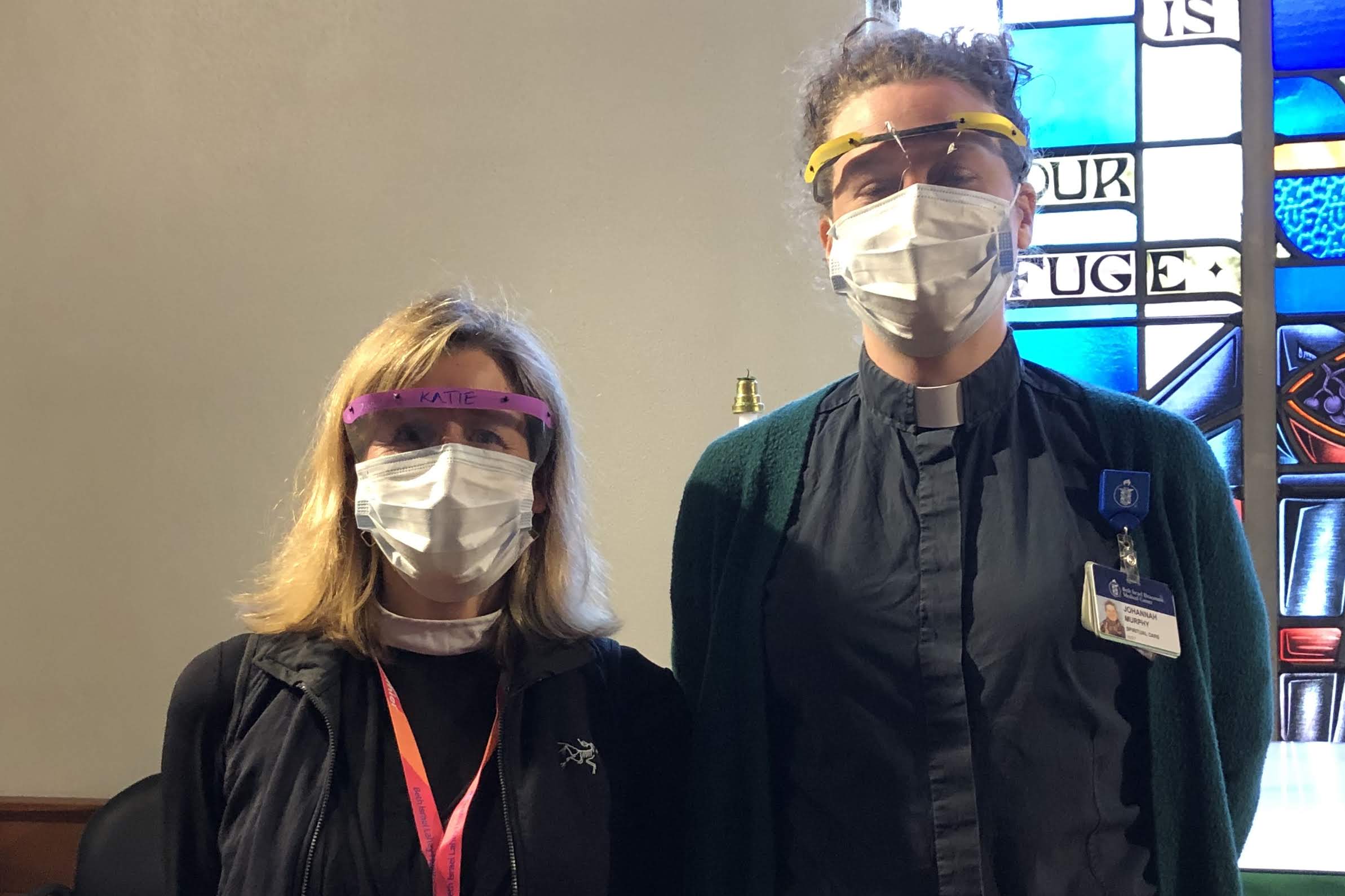

Katie Rimer is the director of spiritual care and education at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Rimer is among a small group of chaplains who come into the hospital during the pandemic while others provide phone support.

This helps explain why Rimer, an Episcopal priest, responded when a Jewish patient with COVID-19 "took a turn for the worse” and his family asked that a rabbi read a prayer for the sick, the Mi Shebeirach. The man and his roommate were both on ventilators and unconscious so Rimer read from just outside, her hand against the room’s glass window.

“All of our lives are so strictly managed by these boundaries,” Rimer says, adding that she’d always want to be at the bedside, reading, even if the patient is unconscious. While Rimer was abiding by medical boundaries, she was crossing boundaries too, reading prayers outside her tradition, hoping that somehow this man and his family would be comforted through her voice at the window and hand on the glass.

Rimer says she sees boundaries fall every day during the pandemic, when hospital staff stop her in hallways or in break rooms to ask for an intimate moment of prayer — and when she calls doctors and nurses to ask, "how are you holding up?"

Rimer says the pandemic forces chaplains "to do things differently and creatively and not perfectly." In the case of the Jewish patient, she adds, "I do hope that we did well for this man and his family and for the many, many others who are in this experience that is most unusual and most extraordinary."

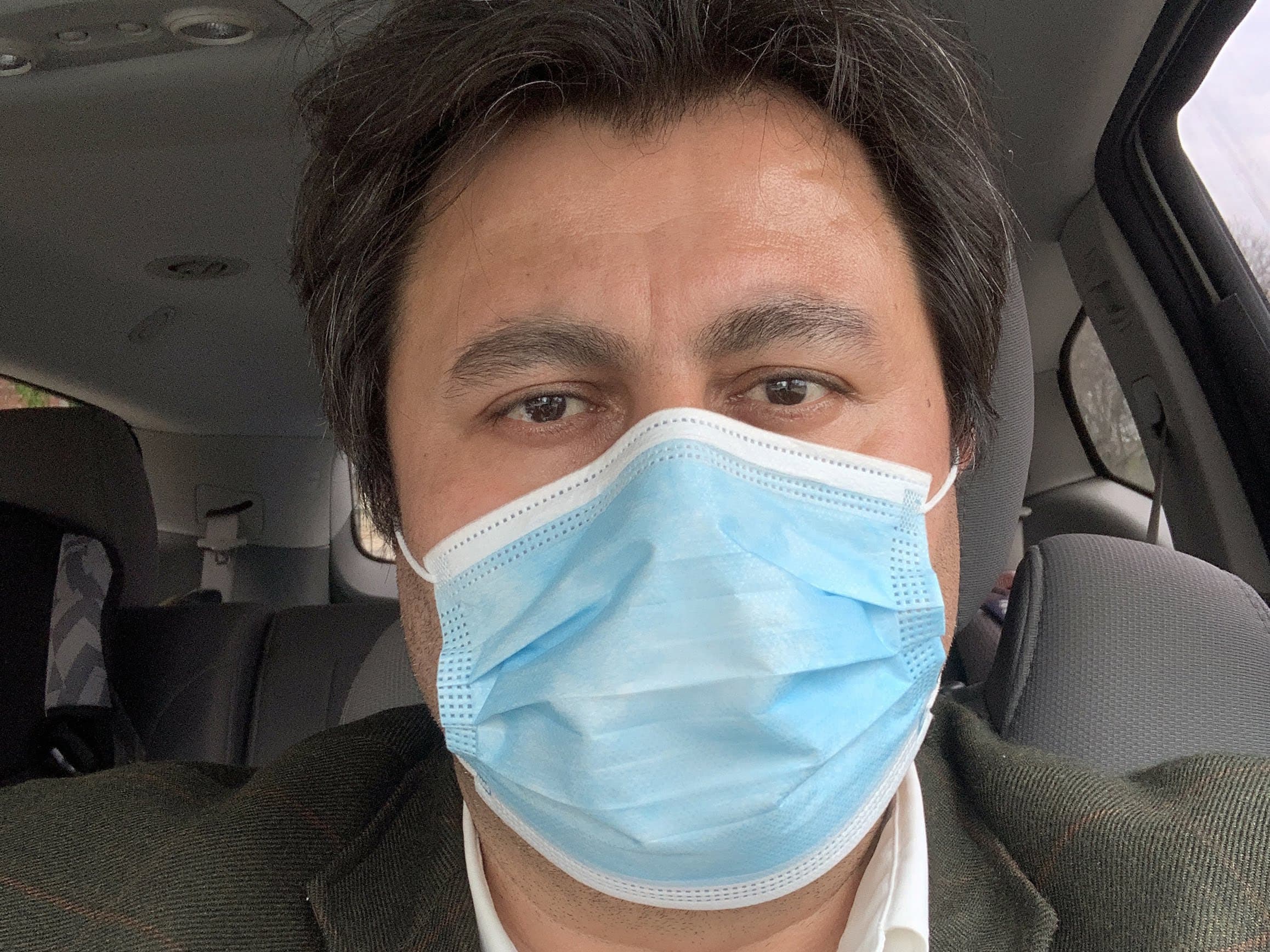

Ibrahim Sayar is an imam on staff at Boston Children’s Hospital. He works part time at Brigham and Women’s Hospital as well.

Because there are so few imams at Boston hospitals, Sayar prepared guidelines for staff dealing with Muslim patients at the end of life. They include passages to read from the Koran as the patient is dying, as well as suggestions about how to find the prayers on YouTube. Sayar delivers holy water from Mecca when he can.

“Chaplains are dedicated to being present,” Sayar says. “With social distancing, which is so important, it’s been challenging.”

Sayar can’t hold the hand of a patient in distress or get close enough to have meaningful eye contact. But he says the gratitude from patients’ families and from hospital staff is uplifting.

“I hope to do my best to be present for our patients and their families, sometimes personally and sometimes virtually, as much as I can,” he says.

This segment aired on May 4, 2020.