Advertisement

Most People Hate Weeds. This Botanist Loves 'Em — Here's Why

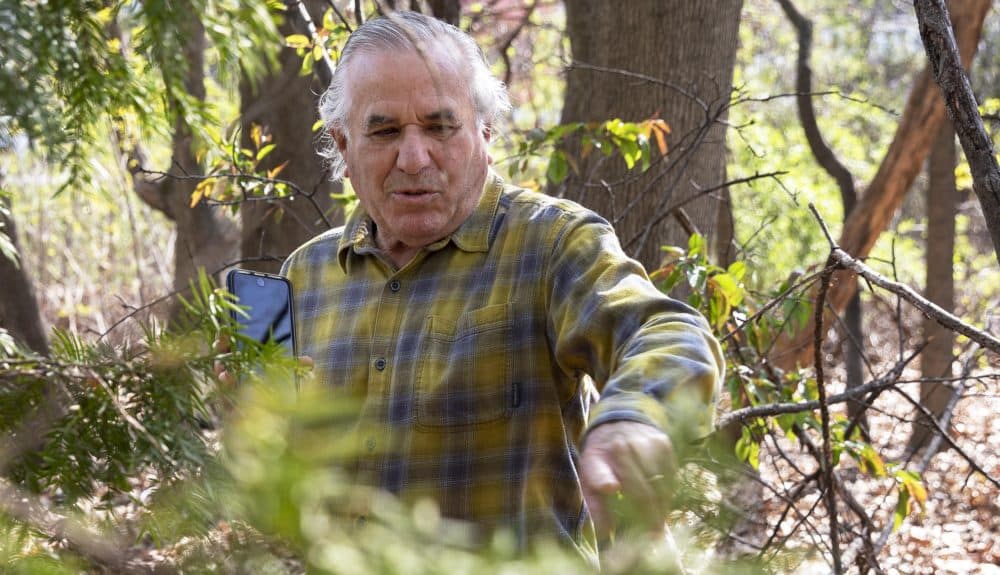

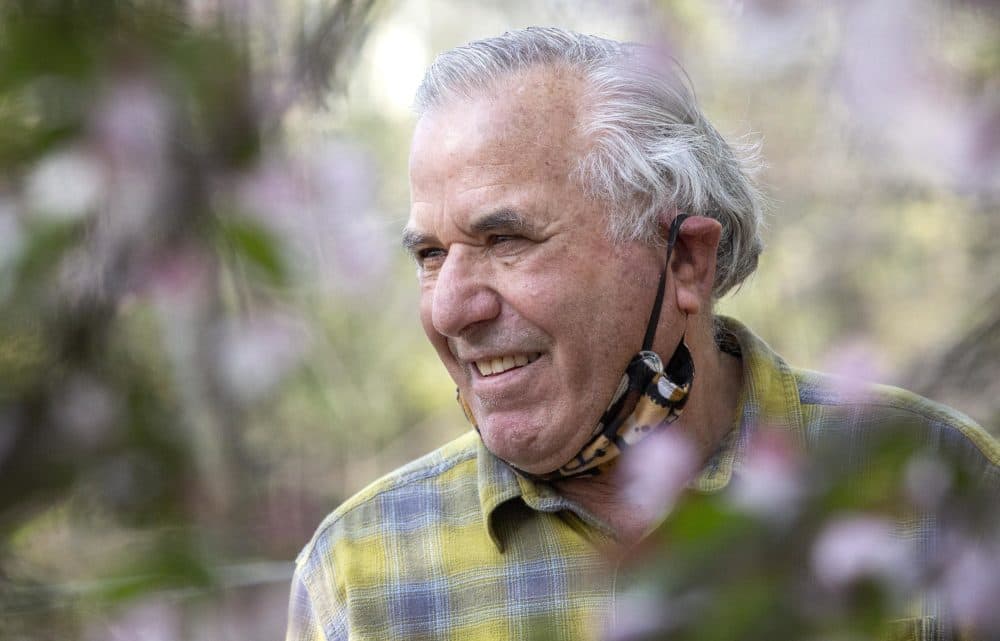

Peter Del Tredici is taking a nature walk. Sort of. He’s making his way through a patch of scraggly woods near the Charles River in Watertown. And he can barely contain his excitement.

“There‘s all sorts of plants here!” he says. “When you go on a walk with me, if we walk more than 500 feet, that will be a major accomplishment. Because everywhere you look, there's something interesting.”

What interests Del Tredici today is ... weeds. Or what he calls "spontaneous urban vegetation." A professional botanist, he worked as a scientist at the Arnold Arboretum for 35 years, curating their bonsai collection and becoming a world expert on Ginkgo biloba trees. But that’s not why he’s rummaging around an urban wild in Watertown on a brilliant spring morning. He’s looking for something a little less refined. He bends down to point out a prickly green plant, growing low to the ground.

“Here you can see the multiflora rose,” Del Tredici says. It was imported from China as an ornamental in the 1800s, he says, but now that it’s escaped into the wild it’s considered an invasive species.

“It’s a very unfriendly plant because it's covered with thorns,” says Del Tredici. “It reaches out and likes to grab people.”

Plants like this have a bad reputation, says Del Tredici, and he wants to help redeem them. For example, he points out, in a couple weeks the thorny plant will bloom with wildflowers. And for many years the federal government promoted the multiflora rose as a way to combat soil erosion. Del Tredici documents these facts and forgotten history in a field guide called “Wild Urban Plants of the Northeast.”

That’s right – it’s a field guide to weeds. Only, he doesn’t like the word “weed.”

"It's not a biological concept at all," he says. "It's just a value judgement. It's a plant you don't like for whatever reason."

Similarly, he avoid the terms “invasive” or “non-native.” Too judgmental.

“I like the word cosmopolitan,” he says. He says the word reflects the reality of a global, ever-changing ecosystem.

Advertisement

“This whole thing about dividing the world up into native and non-native, it's not really all that helpful,” he says. “It explains what existed in the past. But it doesn't explain what exists now and what we're going to see more of in the future.”

Del Tredici says his goal is help us recognize – and maybe even appreciate – the plants we see everywhere but mostly ignore or even despise, like crabgrass and the common reed. (Or some with even better names, like devil's beggarticks, bouncing bet, and spotted spurge.) Yes, some may be ugly, cause allergy attacks, crowd out native plants, or make a move on your vegetable garden. But many are harmless, and some are beneficial — offering shade, propping up riverbanks, and absorbing pollutants.

"There are just so many plants around us all the time that we don't notice, and he draws attention to them," says Rosetta Elkin an Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at Harvard University's Graduate School of Design, speaking of Del Tredici. "How plants move, how they reproduce, how they seed, how they keep going, how they're rogue at times and take over one another, and creep into the cracks — that is just more important to pay attention to than ever."

Like Ralph Waldo Emerson said, "a weed is simply a plant whose virtues we haven't yet discovered." And like it or not, they're here to stay.

"It's not a biological concept at all. It's just a value judgement. It's a plant you don't like for whatever reason."

Peter Del Tredici

Consider the humble dandelion, for instance. Homeowners may pull their hair out trying to eradicate them from their lawns, but why not consider them a fellow-traveler, asks Del Tredici. In spring you can eat the leaves in a salad. You can make the sunny flowers into wine, the roots into tea. (But be careful, the tea is a diuretic.) Del Tredici’s book quotes an early guide to Central Park, which describes “blessed dandelions in such beautiful profusion as we have never seen elsewhere, making the lawns in places, like green lakes reflecting a heaven sown with stars.”

Walking through the Watertown “woods” Del Tredici stops to point out another one of his favorite wild urban plants, a gangly tree with smooth gray bark. It's Ailanthus altissima, the tree-of-heaven. It was introduced into North America from China in the 1800s as a shade tree for cities, and celebrated in the 1943 novel “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.” It happily sprouts from sidewalk cracks, grows quickly, and spreads easily.

But its flowers stink. It can suppress the growth of native trees and plants. And it’s really hard to get rid of. Many states call it an invasive species.

In some circles, it’s known as the tree of hell.

Del Tredici understands why people don’t like the tree-of-heaven. But he takes a different view.

“It grows by itself, which by certain definitions means it's highly sustainable. Because you don't put any resources in, and yet you're getting a lot of benefit in terms of carbon dioxide sequestration, shade production that lowers temperatures, et cetera,” he says. "In an urban context, I think this plant has a lot to offer us...in particular with climate change, we need all the help we can get from nature."

The tree-of-heaven – and other plants with image problems, like knotweed and nettle – are the “flora of the future” says Del Tredici. They can tolerate polluted soil, and sometimes help clean it up. They can handle the hotter summers, heavier storm runoff, and increased carbon dioxide that are coming with climate change. They may even help us survive it.

This article was originally published on May 08, 2020.

This segment aired on May 8, 2020.