Advertisement

Review

New Book 'The Equivalents' Follows Emergence Of Second Wave Feminism From Radcliffe Institute

“Radcliffe Launching Plan to Get Brainy Women out of Kitchen” was how Newsday described the founding of the Radcliffe Institute for Independent Study in late 1960.

The brainchild of Radcliffe College President Mary Bunting, the institute was intended to help “intellectually displaced women” who had excelled academically or artistically, but whose professional ambitions had been derailed by midcentury expectations around motherhood and gender roles.

The idea was simple, yet daring: the college would provide a group of women who had “either a doctorate or ‘the equivalent’ in creative achievement” with a generous cash stipend, a private office and access to the college’s vast resources so they could freely pursue their interests among a community of like-minded thinkers.

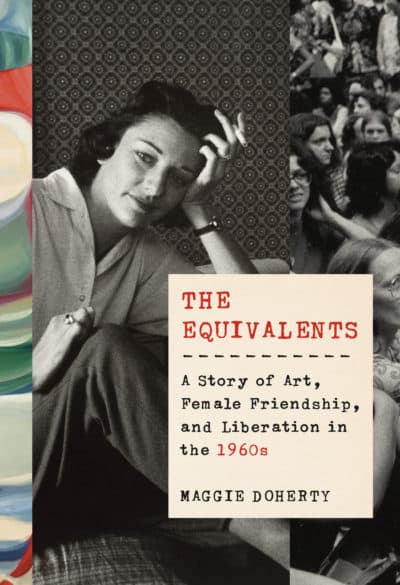

Author and Harvard lecturer Maggie Doherty’s new book, “The Equivalents: A Story of Art, Female Friendship and Liberation in the 1960s,” follows five of the non-doctorate Radcliffe fellows — poets Anne Sexton and Maxine Kumin, writer Tillie Olsen, painter Barbara Swan and sculptor Marianna Pineda — to explore the significance of the institute’s mission and show how it prefigured the women’s liberation movement that would become a defining hallmark of the 1960s.

Or, at least, that’s the intention. The book is full of fascinating information, well rendered by Doherty, on both the history of the institute and the emergence of second-wave feminism following the publication of Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique” in 1963. But the story of the five ‘equivalents,’ who Doherty claims “operated as a hinge… between a decade of female confinement and a decade of female liberation” never quite gels, mostly because the lion’s share of the book revolves around the charismatic personality and tragic life of Anne Sexton.

In fact, much of the book comes off as a straight biography of Sexton, in which the other four women appear as supporting characters. Kumin and Olsen, having known Sexton prior to their matriculation to Radcliffe, are given a fair amount of attention, but Swan and Pineda hardly factor into the story at all — far more time is spent with Sexton-adjacent figures in the midcentury Boston literary scene, like Sylvia Plath and Adrienne Rich. When Doherty dives headlong into the history of mid- and late-1960s feminism in the latter half of the book, the equivalents all but disappear from the narrative.

Advertisement

The awkwardness of the framing notwithstanding, the book is rich with insight into the challenges faced by midcentury women as they struggled to pursue their work. “Not a moment to sit down and think,” writes Olsen, who, unlike most of her peers at the institute, was a working mother. “I am being destroyed.” In her idyllic home in suburban Newton, Sexton describes feeling “like a caged tiger,” pent up with stifled ambition.

To them and many other women of the time, the institute was a godsend; when the program was announced, Radcliffe was inundated with hundreds of applications and phone calls from women desperate for a chance to finally realize their dreams.

But Doherty notes that, in reality, the institute mostly bestowed its prestige and financial support on women who had “somehow managed to find many of these things already.” The women in the first classes of fellows were a homogenous bunch: white, well-off and relatively accomplished. Olsen and Sexton were already acclaimed writers; Olsen’s short story collection had been named one of the 10 best books of the year by Time magazine just before she was accepted. Sexton used her stipend not to support her writing, but to put a pool in her backyard.

Doherty writes that the institute as originally conceived “failed to address the particular concerns of working-class women and women of color.” It’s an important observation, but it also makes the book’s emphasis on Sexton and her friends seem questionable — especially when Doherty reveals that Alice Walker was a Radcliffe fellow in the early 1970s.

Doherty’s chapter on Walker describes how she discovered the writing of then-obscure novelist Zora Neale Hurston while studying at the institute, and how she worked to elevate Hurston to her rightful place in the literary canon. Arguably the most famous alumna of the Institute, Walker’s work both during and after her fellowship seems to perfectly demonstrate Doherty’s thesis that the institute was a locus of “influential feminist art and thought.” Indeed, part of Walker’s seminal “womanist” work “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens” was first delivered as the keynote speech at a Radcliffe symposium.

But it’s Anne Sexton whose picture graces the cover of the book. Less attention is paid to Walker’s achievements than is devoted to a spat between Olsen and Kumin about the former’s refusal to blurb the latter’s novel. With “The Equivalents,” Doherty sheds light on an important story, one that takes place at the fraught intersection of gender, race and class. While the lens through which that story is told may be a little out of focus, there’s still much to be learned from it.