Advertisement

Review

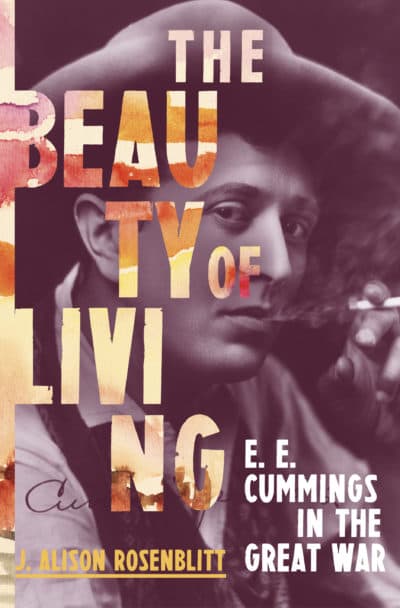

Biography 'The Beauty Of Living' Examines Experiences That Shaped Poetic Voice Of E.E. Cummings

In late 1918, E.E. Cummings sat down in a barracks at Camp Devens in Massachusetts and began to write.

“Art is vital,” he wrote. “Art is indeed that superfluous crisp minute inexcusable impulse which substitutes the actual synthesis of premeditated vitality for a probable comedy of cellular agglomeration, amoeboid improvisations, corpuscular statistics, or mess.”

Satisfied with this high-minded statement of purpose, he flipped the page over and covered it, says author J. Alison Rosenblitt, “with erotica.”

Therein lies the charm of Edward Estlin Cummings — on one side, a tangle of lofty modernist ideals worthy of T. S. Eliot, on the other, a vulgar fascination with sex that recalls James Joyce at his most transgressive. It’s this cheeky blend of high and low that makes his poems so memorable, so popular, and so widely read.

In “The Beauty of Living” (out now), Rosenblitt explores Cummings’s youth in Cambridge, his studies at Harvard, and his time in France during the First World War, providing an in-depth look at the experiences that shaped his unique poetic voice.

Cummings had been drafted by the U.S. Army and sent to Camp Devens with the expectation that he would soon be deployed to France to fight the Germans — a strange turn of events considering that just six months earlier, the U.S. government had expended a significant amount of effort getting him out of France.

He had gone there in 1917 as a volunteer for the Norton-Harjes Ambulance Corps, a popular choice among Cummings’s coterie of Harvard-educated literary types, young men who wanted to experience the frisson of war without having to shoot anybody.

Unfortunately for Cummings, his friend William Slater Brown sent a few letters home that were critical of the French war effort. When the censors saw them, Brown and Cummings were arrested as “undesirables” and locked up in a detention camp. Cummings spent about four months in jail and was freed only thanks to the entreaties of the U.S. State Department. Fortunately for him, the war ended before he could be sent back as a soldier.

Advertisement

Rosenblitt proposes that, since Cummings’s poetry was influenced by what he witnessed in France, he should be considered a “war poet” alongside Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. “We do not normally think of Cummings as a war poet,” she writes, but insists “we must understand this period of his life if we wish to understand his ideas about love, justice, injustice, humanity and brutality.”

It’s a bit of a stretch. Cummings’s writing on the subject is elliptical (“i have seen / death’s clever enormous voice / which hides in a fragility / of poppies…”) — a far cry from the visceral narratives of “Dulce et Decorum Est” or “Counter-Attack.” The tone signals Cummings’s status as an observer rather than a participant. From his position on the margins, he is able to aestheticize the sights and sounds of battle in a way that would be inconceivable to those who endured the nightmare of the trenches.

Owen and Sassoon became famous for their stinging, anthemic poems illustrating the horrors they saw in vivid detail; Cummings through his playfulness with language, form, and convention, habits that seem more rooted in his need to rebel against the strictures of life growing up in Cambridge or the rigidity of his education at Harvard.

Indeed, Rosenblitt does an excellent job of describing Cummings’s artistic evolution in the days leading up to the war: the influence of the classical paganism and Decadent poetry he picked up at Harvard and his excitement over pre-war modernist movements like cubism, futurism and imagism. The war, while important, was if anything just a final nudge toward the break from convention that he’d long been aiming for.

The five weeks he spent in Paris awaiting his assignment with the ambulance corps seem to have had a much greater effect on his poetry than anything he saw near the front. While there, he struck up a relationship with an older woman named Marie Louise Lallemand. Rosenblitt points out that Cummings’s relationship with Lallemand has been poorly treated by previous biographers who seemed unable to reconcile their genuine intimacy with the fact that she was a sex worker.

But Rosenblitt gives the woman her due. Lallemand is more than just Cummings’s muse. She helps him recognize the power in the passion and sexuality he spent much of his youth trying to suppress. Their relationship is a watershed for Cummings; by unlocking this side of himself, he taps into a vast reservoir of feeling that can be seen throughout his later work.

The subtitle of this book, “E.E. Cummings in the Great War,” undersells what is a thoughtful, engaging story of an artist discovering his voice. Rosenblitt’s depiction of both Cummings and the elite, early 20th-century literary world in which he moved make it a fascinating read, and the dialogue she opens with previous biographies of Cummings’s life regarding Lallemand’s role in it make it an important one.