Advertisement

Sara Faith Alterman Shares Humor And Heartbreak In Memoir 'Let's Never Talk About This Again'

Sara Faith Alterman is not a dark person. She likes to laugh with people and make them laugh. She has done that writing humorous novels and, earlier in her career, writing sketch comedy for ImprovBoston, and currently helps other people find the laughs in their high school embarrassments as a producer with the “Mortified” storytelling show. The story she tells in her new memoir, “Let’s Never Talk About This Again” (out now), required a different approach. It is a tribute to her father Ira’s influence on her sense of humor and writing career, but it is framed by the battle with Alzheimer’s Disease that he ultimately loses.

Alterman can be silly, and she frequently indulges in her love of wordplay. The main story, broken into the “Before,” “During” and “After” of Ira’s Alzheimer’s, is heartbreaking, detailing how he loses his job and deteriorates rapidly cognitively and physically, slipping further from his family’s reach. She presents these dark and light moments together as a matter of fact — they are often happening simultaneously. The DNA for this nuanced tone is evident in the first two paragraphs. She writes:

I am pundamentally a word nerd. It comes from my father, or came, I guess. Past tense. He died. But his puns live on posthumorously.

Dad’s name is Ira, or was. I don’t know if a box of dust can have a name. I guess Ira is as good a name as any for a box of dust.

Alterman didn’t want to be coy about the fact that her father dies in the end — she hates when writers do that. “I just wanted to establish the stakes of the book right away,” she says, speaking by Zoom from her home in San Francisco, “but I wanted to do it in a way that didn’t feel doom and gloom, and felt like it did set the tone of the book, which is, ‘I’m going to talk about difficult and sad things, I’m going to try to do it in a way that is funny and hopefully fresh, but not in a way that feels like I’m either making light of death or trying to joke around my own pain.”

In one section, Alterman goes with her parents when they visit the doctor who diagnosed Ira. She feels angry and wants to blame the doctor for claiming her father had this condition, but she can’t help but turn it into alliteration. She writes that she almost said the phrase, “doctor dared diagnose Dad’s dementia,” which she thought her dad would find funny, but the doctor cut her off. “I think I process most of my life through ways that my father influenced me, which is good and bad,” she says. “I still find myself, now, making the same hokey jokes to my son’s teachers that he would make to my teachers.”

In many ways, Alterman has followed in her father’s footsteps. Ira wrote for Boston After Dark, which became The Boston Phoenix by the time Alterman wrote for them. He used his sense of humor in print, writing illustrated novelty books with titles like “Games You Can’t Lose,” and told his kids original bedtime stories. Alterman admired how quickly her father could find the right word, and she would often seek his collaboration after she started writing professionally. “I would call him and we would approach writing sentences as math problems to be solved,” she says. “It was the most fun that we had together, was just kind of working together to brainstorm an adjective. Which is so nerdy! But we just loved it.”

Not everything he wrote had a positive influence. Alterman writes about finding a stash of racier books her father wrote on a high shelf when she was a kid. Humorous, illustrated sex manuals and one series featuring photographs of a rotund woman named Bridget nude or partly nude, whose sexuality was the butt of the joke. Seeing those books as an adolescent contributed to negative body images that made Alterman self-conscious. “It’s funny, but as a teenage girl, I remember very much internalizing this notion that if you’re fat, you deserve to be made fun of,” she says. “Which, as a teenage girl, you’re getting from the kids around you anyway, but to get it from material that your father created was especially difficult.”

The fact that Ira would write these books was surprising to Alterman since her family didn’t like to talk much about difficult subjects like sex — that’s where the title of the book comes from. On movie nights, her dad used to forward past the “kissy” parts so the kids wouldn’t see them. Alterman never discussed the books with her father, something she has mixed feelings about now. “These books were always such a source of discomfort and confusion for me that I wish we’d sort of cleared the air about them so that I could hear the story behind them,” she says. On the other hand, if her father was truly piggish and fat-shaming, “I kind of didn’t want confirmation of that.”

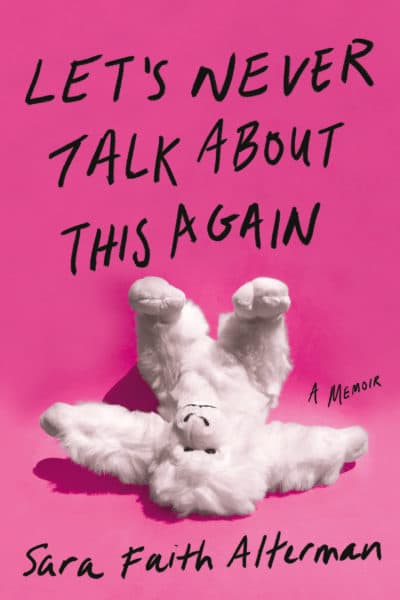

Alterman also shows her father’s protective side. The cover of the book shows a stuffed animal gorilla with white fur, which represents a toy Ira once gave to his daughter when she was having nightmares. He called it a “dream gorilla,” and told her if she ever felt scared, it would “grow really big, and scare away the monsters.” Later in the narrative, when Alterman is dealing with a newborn son and watching her father slip away all too quickly, she admits to him that she wishes she “had someone to scare away the bad guys again.”

“Nah,” her father says in the book. “You’re the gorilla now.”

It’s an emotionally devastating line. Not only was it exactly what Alterman needed to hear, but it also came at a time when her father’s mind was firmly in the grip of Alzheimer’s. “It was a really powerful moment for me because it was one of his last moments of clarity when he was alive,” she says. “But also so evocative of the person I always knew him to be.”

There is some irony in interviewing someone who wrote a book titled “Let’s Never Talk About This Again,” in which they repeatedly mention a family proclivity to avoid impolite conversation. And Alterman admits that interviews make her nervous — she’d much rather communicate through her writing.

But she has no problem talking about the book (she’ll even talk about it in public for an online event for Harvard Book Store on July 30). Writing it gave her the chance to evolve into someone who speaks more freely about things that make her uncomfortable. “Initially the book was going to be just a collection of funny essays about my zany dad,” she says. “And I connected with the woman who ended up becoming my editor, Suzanne O’Neill, and she said, ‘no, I love your writing but I think this is a long-form memoir. I think you need to allow yourself to be much more emotionally vulnerable and accessible.’”

Ira died in 2015, but Alterman was still grieving when she started the book two years ago and still finding new things about her father, sorting through boxes of her father’s books and personal items her mother sent her for research. She is proud to have been able to include one of his children’s stories in the final chapter and hopes the opportunity might arise to publish more of his writing posthumously.

Writing a keenly honest book about him was a catharsis, but sending it out into the world without being able to talk to him about it is bittersweet. “The same way that he and I used to put our heads together about words,” she says, “I don’t get to put my head together with his about the experience of writing books.”