Advertisement

Even As Diversity Grows, Mass. Schools Remain Segregated

Resume

En español, traducido por El Planeta Media.

Even as Massachusetts grows more diverse, a growing number of its public schools are becoming “intensely segregated.”

In a new report, education researchers argue that as a result, thousands of students miss out on the many benefits of learning in a diverse community — and that, as citizens demand racial justice, state officials are failing to confront the trend.

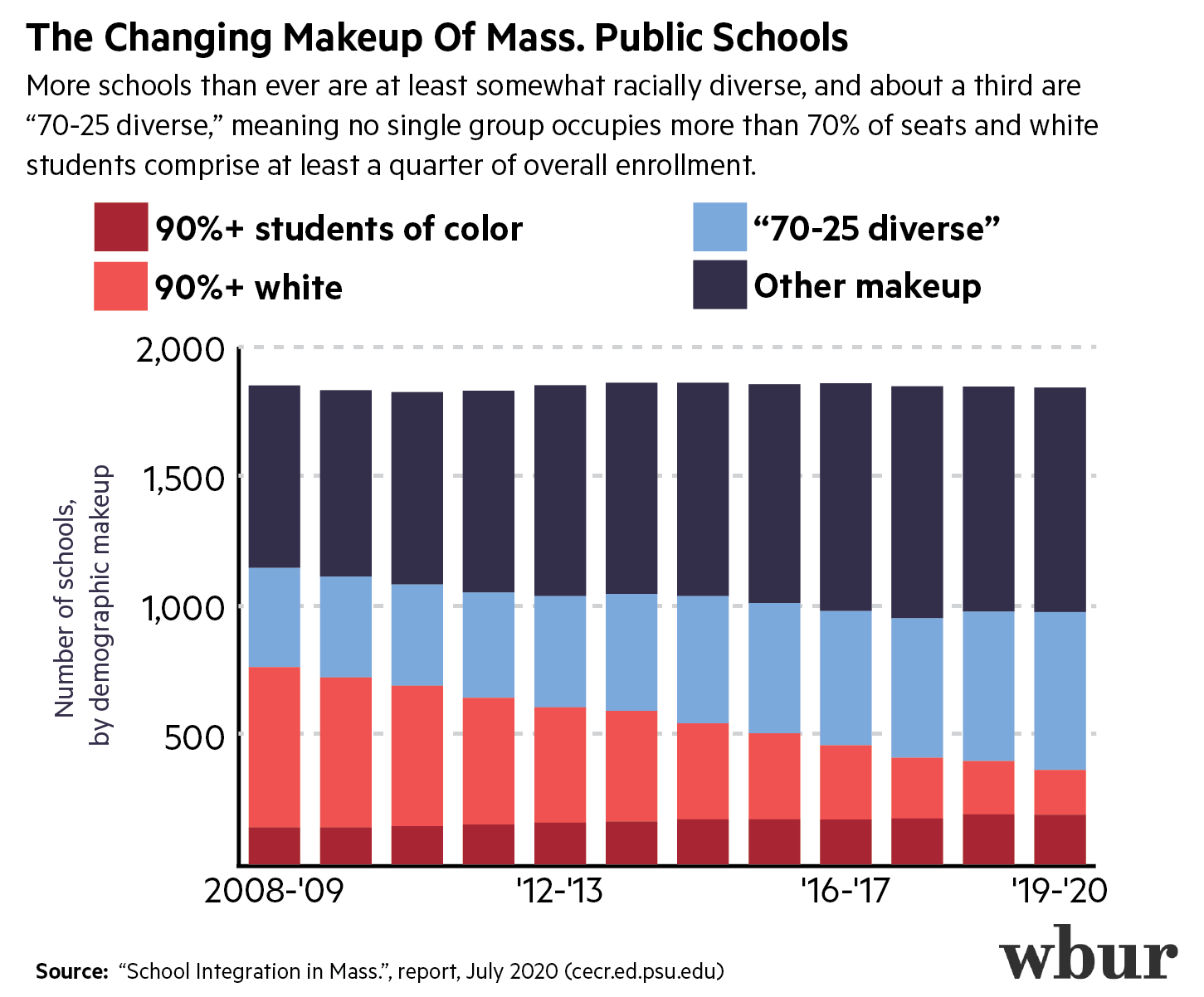

At first glance, the report seems to present a picture of the state’s public-education system, somewhat rapidly, becoming more diverse in more precincts. For instance, the number of schools with overwhelmingly white enrollments has collapsed over the course of just over a decade — from 619 in 2008 to 173 in the latest data.

And more schools than ever are “70-25 diverse” — meaning that no single group occupies more than 70% of their seats and white students make up at least a quarter of overall enrollment.

The report authors cite a finding that schools in that category are more likely to incubate cross-racial friendships among students and that students in the racial minority are less likely to report feelings of isolation.

Peter Piazza, an education researcher and one of the report authors, said that, as a white parent in a charged political moment, that sort of environment is especially meaningful.

“I went to highly-segregated white schools. And it’s taken a long time for me to learn about systemic racism and all of the things people are out in the streets protesting right now,” Piazza said. “I don’t want that for my kids. I want them to understand their society, in its complexity, as early as possible.”

But Piazza warned against a kind of optimism based on the overall trends, saying that the problem of intense segregation — wherein either white or students of color make up 90% or more of a school’s enrollment — hasn’t gone away, only taken on a new form.

“The last thing I’d want somebody to take from the report is that demography, left alone, will save us,” Piazza said.

He and three co-authors found that even as there are now 72% fewer “intensely segregated” white schools in the state than there were in 2008, there are also 33% more “intensely segregated” schools serving almost exclusively students of color. The report counts 192 such schools, including 65 in Boston alone.

That could — and should — change, argued Jack Schneider, a co-author and professor of education at UMass Lowell.

“Of the nine districts with intensely segregated non-white schools, six of them have the districtwide demography to produce uniformly diverse schools,” said Jack Schneider, another co-author. “So this is something that only requires the political will to solve.”

When asked why predominantly Black and Latino schools represent a problem in need of “solving,” Schneider — who is white — made one thing clear: “There is nothing magical about white children.”

Indeed, he added, forthcoming research from his team will argue that white students may gain more than any other group from integrated learning environments.

Instead, his argument was based on white families’ disproportionate “grip” on economic resources and political power in Boston and nationwide. If schools become more diverse, Schneider said, “white families — in advocating for their own kids — will also be advocating for resources” for students of color.

Moreover, Schneider argued, the sense of isolation for students in the minority at a segregated school is real. “When [students of color] look around and they don’t see anybody in their schools who looks like the existing power structure… they will know that those with a choice have left. That does send a powerful message.”

Asked for comment on the Boston-related findings of the report, Boston City Councilor Andrea Campbell said she was not surprised.

"I live in Mattapan. I can drive from downtown to my neighborhood and see the segregation," Campbell said. "Right now, the way our system exists — there’s a narrow pathway to a successful experience in BPS... While communities of color bear the burden of those inequities, everyone should be concerned."

In a plan released last summer, Campbell called for the reworking of Boston's controversial school-assignment system to make more quality seats available to students from her neighborhood and others like it — but she said there's been "little movement," one year on.

Campbell said that increasing student diversity at the school level is "not going to fix the problem" on its own. She called for "political will and bold action" to increase teacher diversity, revamp high schools and other school-quality improvements in the district.

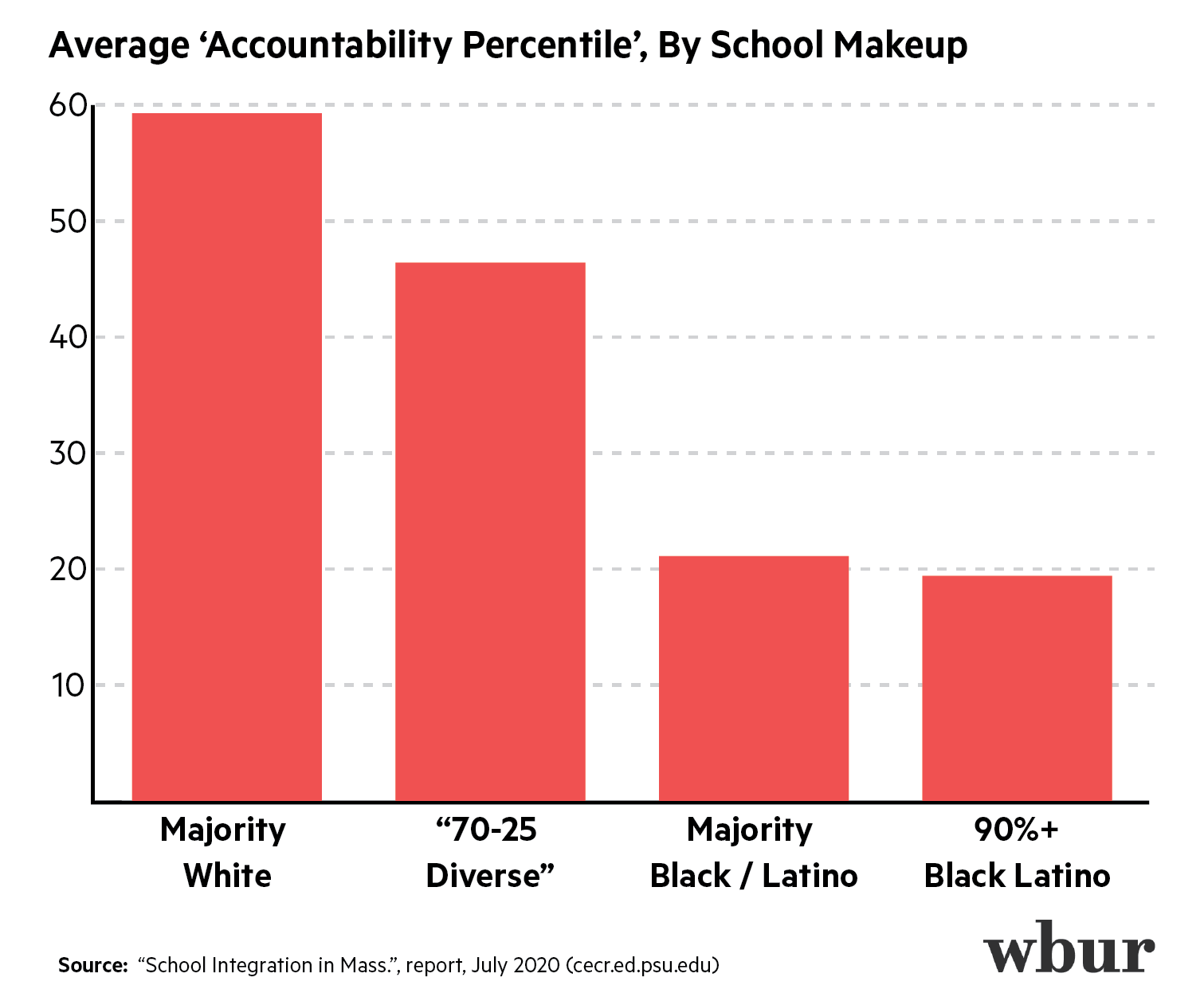

The main upshot of the report is to argue that the state accountability system — by which schools are monitored and ranked, based largely on their scores on the MCAS test — fosters bias and misconceptions.

Schneider runs the “Beyond Test Scores” research project at UMass Lowell, and has been an outspoken critic of school-quality evaluations based on standardized tests for years. He argued that the state still leaves parents with the false idea “that they have to choose between good schools and diverse schools.”

Piazza added that he believes that low test scores “feed into a public perception of Boston Public Schools that I don’t think it entirely deserves… There are fantastic things going on that you won’t read about” in the district — in part because they're not so easily quantified.

The report authors document a stark relationship between schools’ demographic makeup and its ‘accountability percentile’ — where the state rates it on overall quality.

Some parent-advocates resist the idea that tests or state regulators are to blame for students’ divergent experiences based on race. Among them is Keri Rodrigues, head of Massachusetts Parents United, who has advocated for charter schools among other education reforms.

Rodrigues highlighted the work of the Brooke Charter School, where an overwhelmingly low-income, Black and Latino students post among the state’s top MCAS scores.

“[They’re] able to achieve — because they have resources, they have excellent teachers… and they work hard to intentionally overcome the belief gap,” Rodrigues said. “Why would we not replicate that?”

Both Schneider and Piazza work on the Massachusetts Consortium for Innovative Education Assessment, which is piloting a more holistic alternative measure of school quality, including diversity itself.

Schneider himself isn’t persuaded by the charter-school outliers. “When schools focus intensely on improving standardized-test scores, they can improve those scores. At what cost?,” he asked.

He said the state has given lawmakers and families “the equivalent of Yelp reviews” of schools, when nearly everyone is “smart enough and interested enough to dig deeper” into what schools do well in terms of providing welcoming, rich — and diverse — environments.

Rodrigues, in turn, said that test scores are among the few data points she trusts in “a racist system.”

“Parents are very concerned not just about whether kids are having a joyful experience,” she said.”When they leave the education system, they better have an education that’s worth something. If they don’t… they’re going to have a very, very unhappy life.”

At the close of the report, Schneider, Piazza and their co-authors raise multiple suggestions to improve diversity in the state's public schools schools, from the district level up.

They highlight the “controlled-choice" model used in Cambridge, which cultivates diversity in schools by giving priority to prospective students who would push the schools into mirroring the district at large.

Campbell — along with experts at the Boston Area Research Initiative — has called for a more modest change in that vein, guaranteeing more high-quality seats for students from underserved communities in the school-assignment algorithm.

The report's authors also recommend cross-district solutions — for instance, students from majority-Latino Lawrence traveling to schools in largely white North Andover, and vice-versa — but those would seem to be larger political lifts.

The authors, Campbell and Rodrigues are informed by the ugly political cataclysm that broke out almost 50 years ago as Judge W. Arthur Garrity, along with community leaders, tried to integrate Boston's schools. Today, advocates share a goal to settle the issue of school-to-school equity for good, albeit sometimes by very different means.

“Our history on this issue is not good. I understand why people sense a general hesitation to go back, because of how vitriolic the response was,” Piazza said. Then he pointed to unrest in the streets of Boston and the nation at large, and to calls for reparations and reform.

“Times are different. And if we fear having that conversation again, we’ll never get started.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misrepresented Massachusetts Parents United as a group that "advocates for charter schools." The group does not explicitly support charter schools and is ‘governance-agnostic.’ We regret the error.