Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

Data Shows Many In Mass. Have Left The Workforce

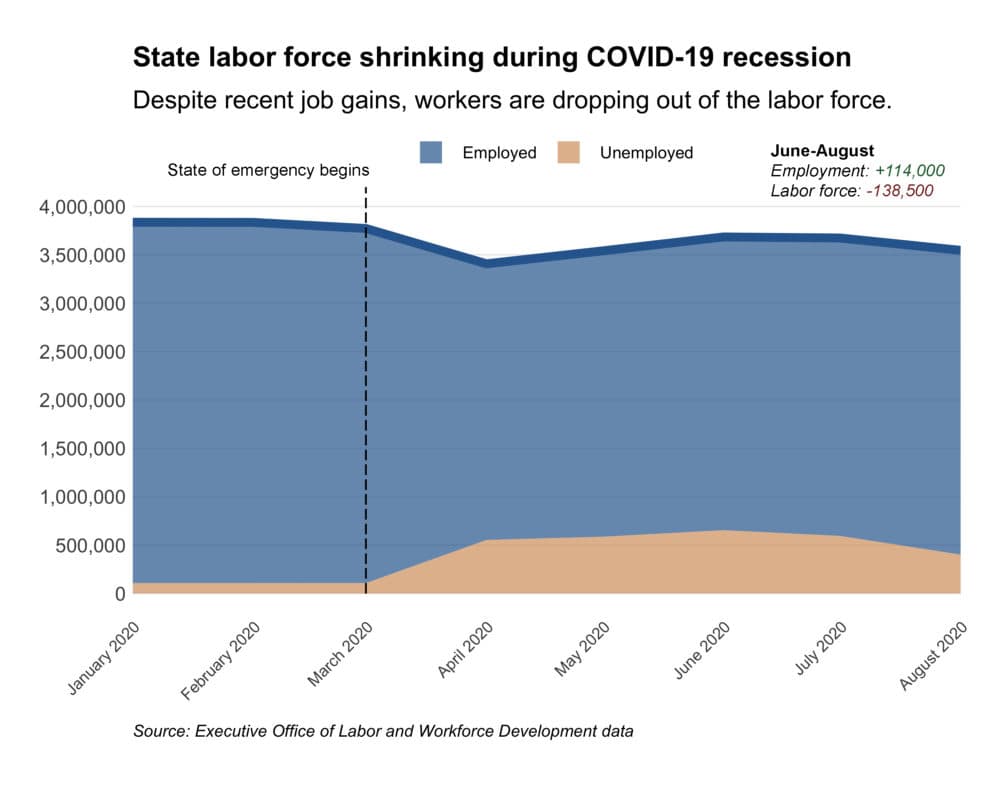

The number of Massachusetts workers counted as unemployed dropped by more than 250,000 over the past two months, a decline of more than a third that helped the state escape from a short streak of owning the worst jobless rate in the country.

About 114,000 more workers became employed in that span, too, a sign of continued steps toward recovery following the pandemic-related recession's low point in the spring.

But the improving jobs numbers and unemployment rate likely mask deeper, more lasting damage at both the state and federal level: many people are dropping out of the workforce altogether, hinting that some — particularly women, who disproportionately fill caretaker roles — have given up attempts to find employment amid slow hiring and uncertainty about the COVID-19 health outlook.

"It's a significant problem," Federal Reserve Bank of Boston President and CEO Eric Rosengren said in a speech on Thursday. "The longer the pandemic goes on, the more you're going to see people leaving the labor force, not only because they can't find a job, but because they have to care for either elderly parents, people that are sick because of the pandemic, or children that are not able to go to school because schools have been closed and there is not availability of daycare."

The trend, according to economist Alicia Sasser Modestino, indicates that the recent improvement in the state's unemployment situation might be "not as rosy as it might seem."

Between January and August, the working-age population in Massachusetts grew 13,400, according to data published by state labor officials based on a household survey. In that same span, the labor force — which counts both people who are employed and those who are unemployed but actively seeking work — shrunk by 290,000.

The drop was not limited to the earlier days of the COVID-19 crisis, when job cuts were severe. In July and August, a span in which the employed population grew and the unemployed population shrunk, the labor force declined by 138,500 — more than the 114,000 jobs added.

While both Massachusetts and the country as a whole have seen workers depart the market, the trends have taken different patterns.

Advertisement

Nationally, the rate of working-age adults participating in the labor force has been slowly but steadily climbing, reaching 61.7% in August after dropping to 60.2% in April. In Massachusetts, the rate fell to 60.3% in April, rebounded to 65.1% in June, and then fell back down again to 62.6% in August, household survey labor data show.

"We seem to be moving in the opposite direction from the country in terms of the number of people who are participating in the labor force, which means that our improvement in the unemployment rate is maybe not as rosy as it might seem," Modestino, who is associate director of the Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University, told State House News Service. "If some of that improvement is coming from people dropping out of the labor force, that's not how we usually like to improve the unemployment rate during a recession."

Both the fluctuating pattern and the scale of the changes are unusual. In general, the labor force shrinks during recessions and grows during expansions, but — like so much else about the pandemic — this economic slowdown is unprecedented.

Alan Clayton-Matthews, another Northeastern professor who is a senior research associate at the Dukakis Center, said the more acute labor-force changes in recent months reflect the new reality of the pandemic.

"In some sectors, you know you can't get a job right now," Clayton-Matthews said in an interview. "In a normal recession, you might have stayed in the labor force, but in this one where, because of COVID, there's a virtual certainty that you're not going to be able to get a job, you drop out of the labor force."

Another factor, he said, was the now-expired increase in unemployment aid offered through federal programs to blunt the impact of massive layoffs.

While experts said the volatility in the labor force figures raises red flags, they stressed that the state-level data do not offer a clear picture of why workers have departed.

Some could have opted to halt working over health concerns, some could have resigned themselves to not finding a job in the current strained economy, some might need to shift their focus to caretaking, and some might have simply retired during the pandemic.

Many experts agree, though, that the employment impacts have been disproportionately concentrated among people of color, who are more likely to work low-wage jobs prone to disruption, and among women, who often perform a larger share of parenting and caretaking duties.

A survey Modestino conducted found that 13% of working parents either reduced their hours or lost their jobs because they had to take on child care duties during the pandemic. The effects were more concentrated among women, she said.

"Among women who became unemployed during the pandemic, 25% of them said it was solely due to child care," Modestino said.

In February, about 31% of Massachusetts claimants seeking unemployment benefits were women, according to Modestino. By July, that rate had jumped to more than 56%, "a tremendous shift."

A similar trend is occurring nationally. Between February and September, the percent of men aged 25 to 54 participating in the labor force dropped 1.6 percentage points, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data based on the Current Population Survey. For women in the same age range, the labor force participation rate dropped 2.8 percentage points over that span.

"In a pandemic, where many schools are closing, when many people in the 25 to 54 age bracket are having children, many families have to make a choice of whether or not they can continue to work because they have children at home," Rosengren said in his remarks. "Sometimes, that is borne by the husband, but frequently it is borne by the wife."

The long-term effects of discouraged workers may not become clear for months or years, particularly amid enormous uncertainty over the public health outlook.

Key questions remain unanswered, such as when consumers will feel comfortable resuming pre-pandemic routines, when a vaccine or treatment will be available, and whether Congress will approve another stimulus package — that appears less likely after President Donald Trump said Tuesday he would withdraw from negotiations.

Clayton-Matthews described the risk of federal aid falling through as "the biggest sword of Damocles hanging over us."

"The economy seems to be weakening, and without another stimulus, I don't see how it's going to get by until there's a vaccine widely available," he said. "We could see a prolonged recession if there's not more support for incomes like there was in the beginning of this pandemic."