Advertisement

Study: Most Of The Plastic Found In Seabirds’ Stomachs Was Recycleable

Resume

The great shearwater is a seabird commonly seen off the New England coast. It's not particularly striking — to the untrained eye, it looks like a brown seagull with long wings. It eats by diving underwater, grabbing prey and then returning to the surface to swallow it down. The birds aren't rare or endangered, but they can live for decades, and this makes them especially interesting to scientists who study long-term environmental pollutants.

"Because they're long-lived and are eating at similar food web levels as where a human might eat, they’re great indicators of the environment, and they really tell us a lot about the health of this Atlantic system," says Anna Robuck, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography.

Humans dump an estimated 4.8 to 12.7 million metric tons of plastic into the ocean each year, and some of it gets eaten by fish, marine mammals and seabirds like great shearwaters. Though scientists have done a bunch of studies looking a how much plastic animals eat, very few have examined what type of plastic they eat. And knowing where the plastic came from could help us keep it out of the ocean.

Robuck wasn't thinking about plastics at first, though. As part of her doctoral research, she started a project looking for chemical pollutants in great shearwaters. Most of the birds she studied had been accidentally caught in fishing nets and picked up by the federal Northeast Fisheries Observer Program, though a few had washed up on the beach. In all, she dissected 401 birds.

"Every bird I was cutting open had plastics in it," Robuck says. "It just really turned into this kind of mind-blowing thing, like, 'Oh, my word, there's so many plastics in these birds.' "

The project is still underway, and so far she has checked 112 of the birds for plastic fragments, finding them in 98% of juveniles and of 60% of adults. She found about eight to 10 pieces of plastic in each seabird — mostly lodged in the gizzard, the muscular organ the birds use to grind up food. Most of the pieces were small, around the size of a pinkie fingernail.

In one bird, she counted 202 bits of plastic. The plastic debris had ruptured its gizzard and spread plastic fragments throughout its internal organs, killing it.

"There's no way a bird could tell this apart from a potential food item. It's just a colorful little fragment floating around in the environment," Robuck says. "It's really sad to know that they're eating so many of them."

Robuck wondered: What were all these pieces of plastic? Parts of candy wrappers? Bits of bottle caps? Paint chips?

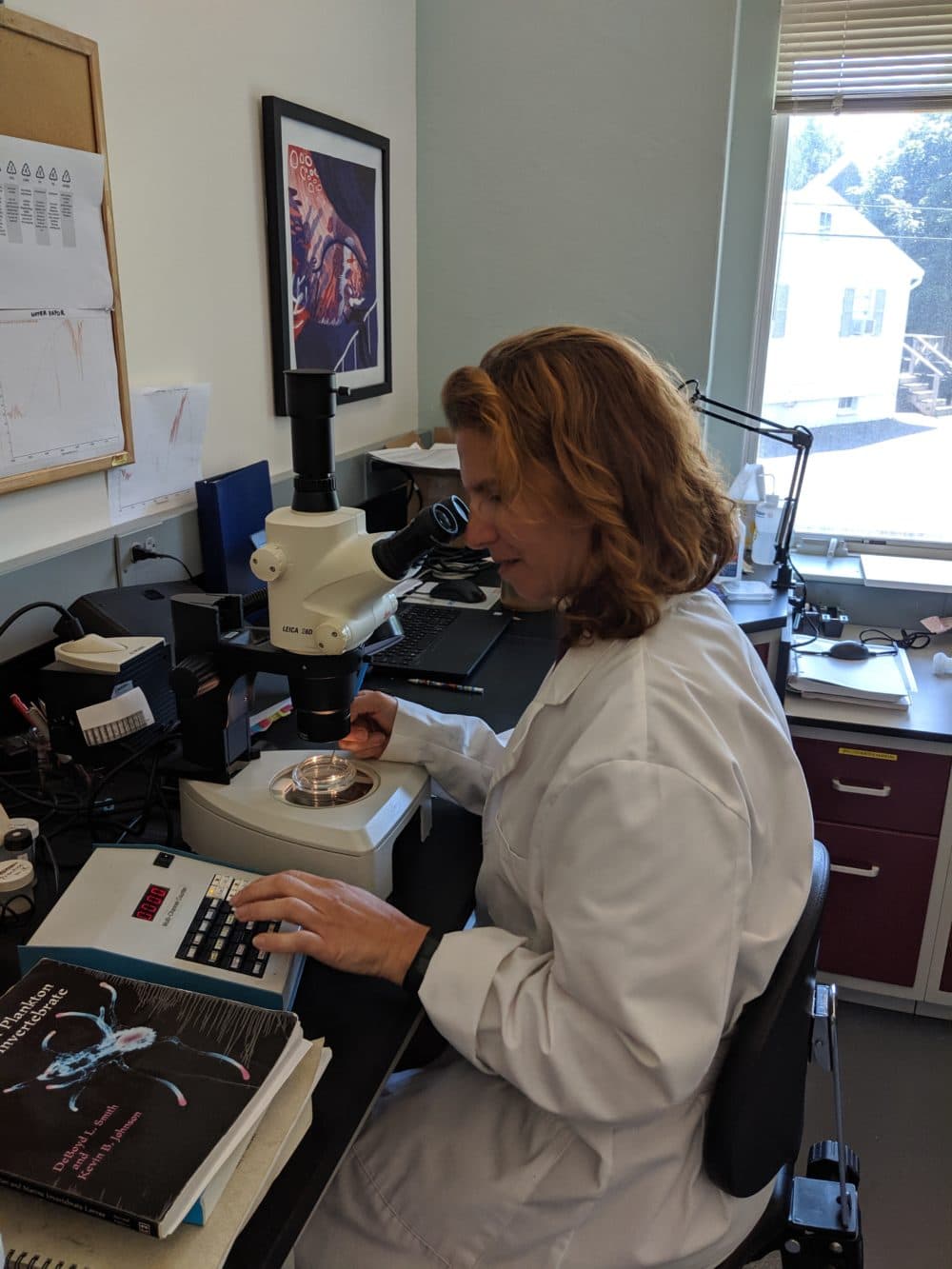

She reached out Christy Hudak, a research associate at the Center for Coastal Studies in Provincetown. Hudak works in the center's right whale ecology program, and her main area of research is studying the plankton soup that right whales slurp down for food. But in recent years, she's carved out a specialty in analyzing the plastic debris that marine animals accidentally ingest.

"She's become sort of the center's microplastics examiner," says Laura Ludwig, who runs the Marine Debris and Plastics Program at the Center for Coastal Studies.

In one recent study, for instance, Hudak analyzed the plastic found in samples of seal scat collected on Massachusetts beaches. (Hudak's colleague Lisa Sette had collected the samples to analyze the seals' diets, and found plastic fragments mixed in with the fish bones.) Using a spectrometer, Hudak identified the plastic fragments in the seal scat as cellophane, resin and rubber.

Hudak agreed to analyze the 1,600-or-so plastic samples that Robuck had found in the Great Shearwaters. Robuck cleaned them, wrapped them in foil, put them in tiny envelopes and shipped them off.

So far, Hudak has analyzed about 1,000 fragments from the birds, finding that most were a common plastic called polyethylene: "Think of it as shampoo bottles or food containers," she says. "And what's interesting is, of all the pieces that we obtained — approximately 1,000 — about 96% of them were recyclable plastics."

To the scientists, the preliminary results add to the growing pile of evidence that recycling is not the solution to our plastic pollution problem, and broader policy action is needed.

"Your most positive thing is just to not use plastic wherever possible. As an individual human, though, that really doesn't have much of an impact," says Ludwig, who advocates for bans on some single-use plastics. "But collectively, when you're talking about 7 billion people drinking water from plastic water bottles, it has a huge impact. And so it really is important to bring your energy for this topic to a different, systemic level."

Humans are ingesting microplastics, too. While there’s no conclusive research showing that this harms us, it’s clearly harming animals that live near the sea. And as the scientists note, we humans are intimately linked to the ocean. So whatever harms it will eventually change the way we live.

This segment aired on October 21, 2020.