Advertisement

2 Mass. Prisoners Hospitalized With COVID-19 Die A Day After Being Granted Medical Parole

Update: The most recent special master report from the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court confirms the men's deaths were not listed as COVID deaths that occurred while in custody. The report, which tracks cases and deaths due to the virus in correctional facilities through Dec. 2, was released Friday and lists 139 current active cases among DOC prisoners and 135 positive correction officers.

Criminal defense attorneys are criticizing how the Massachusetts Department of Correction handles medical parole cases and reports prisoner deaths from COVID-19 following several outbreaks of the virus inside state correctional facilities over the past six weeks.

The attorneys pointed to the deaths of two prisoners who were granted medical parole only after they were hospitalized with COVID-19. In both cases, the men died less than a day after they were granted medical parole. The granting of parole formally removed the men from DOC custody, so the deaths may not be included in the state's reporting of COVID-19 prisoner deaths. It further appears that the men were no longer considered to be in custody, as neither death was reported to the state medical examiner — a requirement for when any prisoner dies.

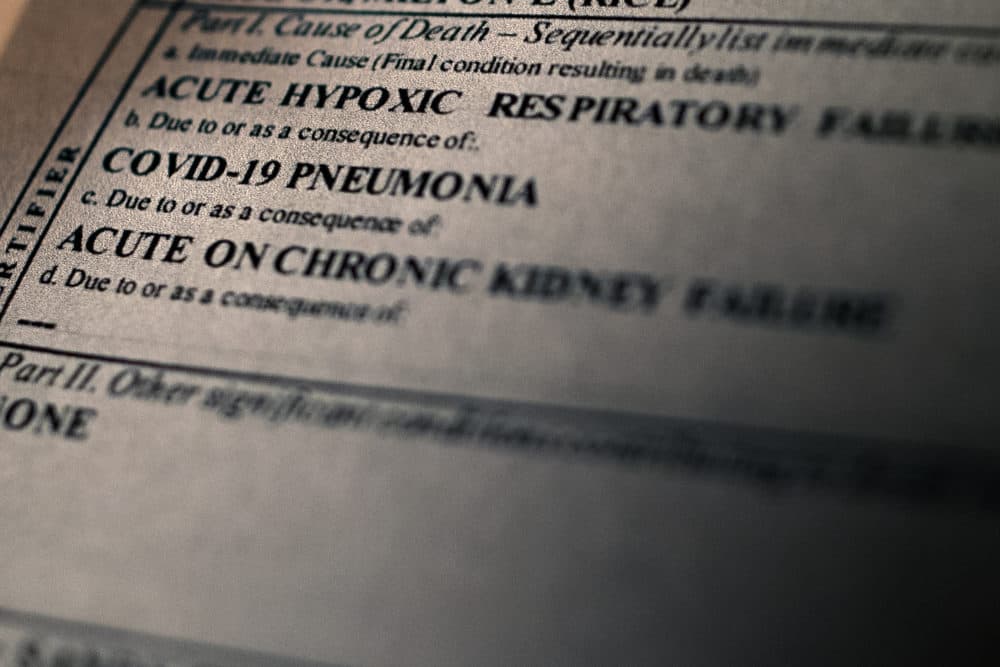

Milton Rice, a 76-year-old prisoner at MCI-Norfolk, died on Nov. 25 in a local hospital where he was taken after he tested positive for the coronavirus two weeks earlier. Rice applied for medical parole back in March, writing "with my underlying health condition and compromised immune system issues, should I contract the COVID-19 virus it would more than likely be fatal for me." His attorney said he was granted medical parole the day before he died. The DOC confirmed Rice was released from its custody as of Nov. 24. The cause of his death is listed as COVID-19 pneumonia.

"I think that the reason for granting medical parole, as far as I can tell, would be to avoid having to report another COVID death of a prisoner within the Department of Correction," said Lauren Petit, an attorney with Prisoners' Legal Services of Massachusetts who worked on Rice's medical parole case. "I don't see any other way to interpret what happened. The request was denied and only granted once the person was on life support, and his circumstances hadn't changed at all."

Advertisement

A similar incident happened amid an outbreak at another Massachusetts prison last month. Defense attorney Ruth Greenberg, who represents several men seeking medical parole, said one of her clients held at MCI-Shirley died on Nov. 20, hours after he was granted medical parole. She said his family does not want his name released to protect their privacy. Just about a week earlier, on Nov. 12, his medical parole petition had been denied.

"The DOC delayed his medical parole petition until he got the disease," Greenberg said. "My client was released about six [to] eight hours before his death, and it appears that was so his death would not be counted as a COVID inmate death at Shirley."

In an emailed statement, the DOC said it continues to focus "on reducing, to the greatest degree possible, the potential impact of the virus.” The department has approved medical parole petitions for 40 prisoners since March, which it said is triple the number of typical successful petitions during that time.

The last COVID-related death at Shirley — or any state prison — was reported in May. The DOC submits weekly reports on the virus in its facilities to a "special master" appointed by the state Supreme Judicial Court. The latest pandemic report, dated Nov. 25, shows that in total there have been eight prisoner deaths at DOC prisons: five at the Massachusetts Treatment Center in Bridgewater and three at MCI-Shirley.

In response to the recent outbreaks, the report said the "Special Master is continuing to work with representatives of the Petitioners, the Department of Correction, and the County Sheriffs to address issues concerning COVID-19 testing and protocols." The special master, attorney Brien O'Connor, did not respond to requests for comment.

"I think that the reason for granting medical parole, as far as I can tell, would be to avoid having to report another COVID death of a prisoner within the Department of Correction. I don't see any other way to interpret what happened."

Lauren Petit, Prisoners' Legal Services of Massachusetts attorney

Massachusetts law allows for the release of prisoners who are seriously ill. According to the statute, a prisoner may be released on medical parole if they are "terminally ill or permanently incapacitated such that if the prisoner is released the prisoner will live and remain at liberty without violating the law and that the release will not be incompatible with the welfare of society."

"Medical parole is a blunt instrument," attorney Greenberg said. "You can't get medical parole just because you might catch COVID. Many prisoners would not be eligible for medical parole unless they actually have it. The statute was not written with infectious diseases in mind."

Infection Concerns Persist

Several other attorneys said they're confused about how the state is reporting coronavirus infections. After an outbreak at MCI-Norfolk this month, there were dramatic fluctuations in the publicly reported rates of infection among prisoners and staff.

The Nov. 12 special master report listed 172 active cases at MCI-Norfolk. A week later, the report said there were just 33 active cases. As of Monday, the DOC said there were 37 cases.

"The problem for a lawyer trying to get help for a client is that we don't have accurate information," said defense attorney Mark Bluver, who is currently seeking medical parole for a client held at MCI-Norfolk. "Despite the orders from the SJC and the reporting requirement the DOC is under, the [infection] numbers seem to be changing with no real explanation as to why they're changing."

Attorneys and several prisoners from both Norfolk and Shirley said they were concerned about prison infection practices and described the prisons as essentially being in "lockdown."

"The prison is on 22[-hour] lock up four days a week, and 23 1/2[-hour] lock up the other three days, which is supposed to go on until Jan. 15th, 2021," a Norfolk prisoner wrote in an email. "Inmates are being placed in greater risk to exposure of the virus from the staff, and nonessential staff were allowed back into the facility for a short time again and then there was an outbreak."

He and other prisoners reached by WBUR said some men are reluctant to report COVID symptoms because it would mean being sent to a quarantine unit. At some prisons that's a crowded dormitory area, which some of the men say is uncomfortable and does not help treat an illness. Another Norfolk prisoner said he and others living in his unit developed symptoms after testing negative, but they didn't tell anyone because they did not want to be quarantined. WBUR agreed not to identify the prisoners, who said they're afraid of retribution for speaking out.

"I can now say, since I am recovered, that I was one of these people," the prisoner wrote in an email. "I had a fever for 5 days running, with difficulty breathing and fatigue. I did not notify medical staff because I did not want to be sent to [the quarantine unit], an open room with 70+ beds. I would have only said something if I absolutely needed to."

Another man held at MCI-Shirley said restrictions because of the virus have taken a toll on prisoners' mental health. As of Monday, the DOC said there were 165 positive cases at Shirley.

"I can tell you that I have been incarcerated for almost 9 years, and I have COVID-19 right now, and the one aspect of my incarceration that I have felt doing the most damage to my psychological well being, would be the unnecessary amount of time being locked in our cells," the Shirley prisoner wrote in an email. "I cannot believe that even right now, they could not allow us to go outside for an hour a day. They could easily lock the gate, as they had been doing, and let us get some fresh air. How is it that the answer to their problems is always, 'lock them up like animals?' "

Virus outbreaks were reported in the past six weeks at MCI-Shirley, MCI-Norfolk, MCI-Concord and North Central Correctional Institution in Gardner. Cases were also reported at Pondville Correctional Center in Norfolk and at Lemuel Shattuck Hospital Correctional Unit in Boston. The DOC says there are currently 13 prisoners receiving treatment at local hospitals.

Questions Around Virus Testing

Advocates and some defense attorneys said the state should increase testing and consider what some other states have done to reduce the number of people incarcerated. New Jersey this month released more than 2,200 prisoners in one day as a result of legislation that allowed prisoners to be set free if they had less than a year left to serve. Advocates here also urged Gov. Charlie Baker to consider clemency. So far, the state parole board has held just one clemency hearing since Baker took office.

Even without releases, advocates said the state could be more aggressive in preventing the spread of the virus in its correctional facilities. They pointed to an agreement reached this month with the correction officers' union to regularly test officers, but noted it does not apply to county jails. The correction officers' union did not respond to requests for comment.

"I think that this is definitely a failure on the part of the state," said Katy Naples-Mitchell, a legal scholar at Harvard Law School. "The fact that these outbreaks are happening was avoidable had there been regular surveillance testing of staff, which are the primary vectors of bringing an infection into a largely closed environment. So the idea that there wasn't testing happening on a regular basis and that it took eight months for the DOC to get the union to negotiate on that is really disappointing, frankly, and an abdication of duty to people who are in the state's custody."

Throughout the pandemic, the DOC, the Baker administration and county sheriffs defended the way the virus is being handled in correctional facilities. In an emailed statement, the DOC said it has done, and continues to do, widespread testing.

"To date, over 16,000 COVID-19 tests have been conducted for inmates across all 16 DOC facilities, which collectively house about 6,700 people," the statement said. "Additionally, day-to-day testing of any symptomatic inmates and patients and their close contacts is also ongoing."

The steps taken to deal with and report the effects of the virus behind bars largely were the result of legal action, and lawsuits are still pending. A hearing is scheduled this week on a motion asking the DOC to adopt a home confinement policy so some prisoners can complete sentences outside of prison. Lawmakers who met with Baker administration officials earlier this month said DOC officials indicated the agency would develop such a policy, and that it could be implemented within 60 days.

"We're very happy to hear that there's at least a commitment to doing home confinement," said Liz Matos, executive director of Prisoners' Legal Services of Massachusetts, which is seeking the motion. "But that doesn't mean that there's a commitment to actually utilizing it to meaningfully depopulate so that we can have a better situation in our prisons and jails and less of a public health threat and crisis, which is what we have now."

In the SJC ruling in April where the court appointed the special master to monitor outbreaks, the justices ruled that some prisoners are eligible to seek release, such as those being held before trial. But there's little clarity on the number of prisoners released solely because of the pandemic.

The most recent special master report indicated that more than 4,400 prisoners have been released from state prisons and jails since April, but that number included scheduled releases as well as those who successfully petitioned to be freed because of the virus. According to the report, the overall number of people in state custody is down by about 1,400 since early April.

This article was originally published on November 30, 2020.

This segment aired on December 1, 2020.