Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

As Clinics Move Vaccination Forward, Confusion And Miscommunication Hold The Rollout Back

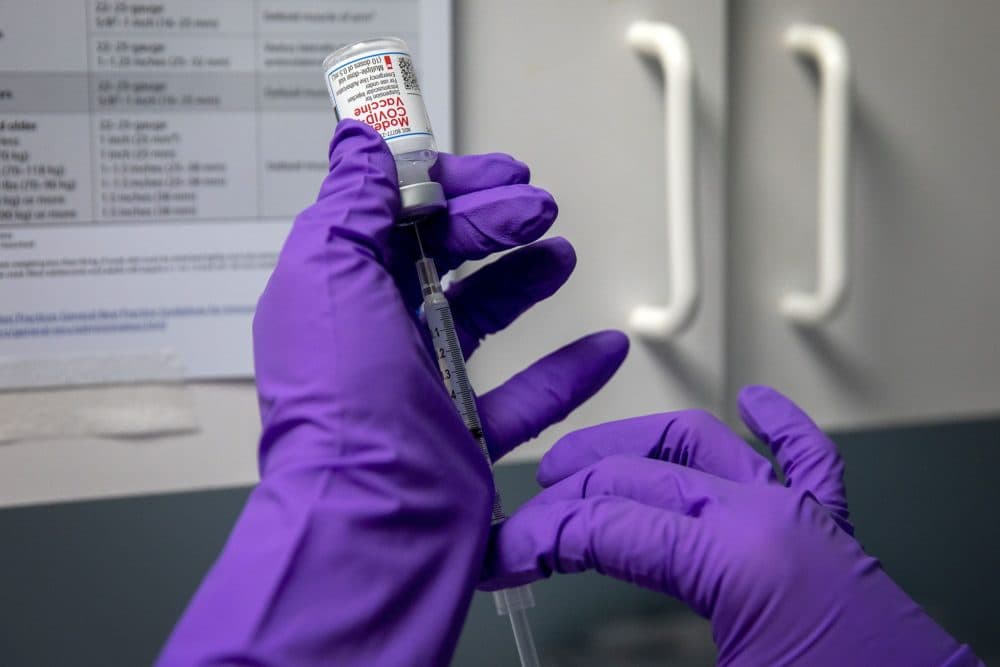

When the first doses arrived in a small, insulated cube, Dr. Sheena Sharma felt a thrill of joy and terror. Packed inside were vials of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccines: 700 chances to protect someone from the coronavirus, Sharma thought, and begin loosening the grip of the pandemic.

“I felt like this huge burden of responsibility," she says, "like someone just gave this to you, and do not screw it up.”

Massachusetts is scrambling to vaccinate as many people as possible against the coronavirus, but limited supply and logistical challenges have hampered the pace of the rollout. The state is lagging behind many other states, including its neighbors in New England.

Many seniors have found it hard to navigate a maze of online sign-up pages. In Sharma’s experience, it’s been like dodging one crisis after another.

“It’s an incredible thing we get to help with,” she says. “But every day I’m prepared for a new obstacle.”

Sharma runs a physician practice with her father in Webster. They wanted to be part of the effort to provide millions of coronavirus vaccines to the public, so they converted the first floor of their three-story health clinic into one of more than 120 COVID-19 vaccine sites opening up across the state.

Now, the building’s glass double doors open onto a complex of registration desks, waiting areas, and vaccination bays. On weekends, patients flow through the first floor, eager to receive their injections. In a storage room, two volunteers stand for hours carefully extracting doses into syringes.

“That’s Katie, our pharmacist. This is our nurse director, Rosanne,” Sharma proudly points to them. “They’re preparing all the doses. That’s what you guys have been doing all day, since 8 this morning.”

“I have good company,” Katie says and laughs.

It almost feels like a miracle to Sharma to see the vaccine site up and running. She spends her nights and free time going back and forth with health officials, trying to make sense of what feels like a bewildering distribution process and a constantly shifting set of rules. Plus, filling appointment slots and managing a separate workforce of volunteers is a full-time job on top of her usual patient visits.

Advertisement

“That part’s been really fascinating in a not fun sort of fascinating way,” she says. “I just wish I had some idea of what’s next, and what pace to expect so we could adjust.”

"It’s really painful to open that fridge and have doses sitting there, and think you’ll just take them out and put them in another fridge because of some process."

The guidance she’s received from health officials has been, at times, nonsensical, she says. The first weekend she was set to open, only first responders and health care workers were eligible for vaccination. But after hours on the phone, she could find only a handful of people near her clinic to sign up.

“I called police and I called fire, and I called every single one. They had all been done,” she says.

And yet, the state wouldn’t let her vaccinate anyone else. It filled her with frustration. Major hospitals had been given more leeway. Laboratory technicians in their 20s had already been vaccinated, but health officials told Sharma she couldn’t vaccinate a social worker in his 70s. If she didn’t use all her doses in 10 days, she would have to send them back.

It made no sense to her.

“You can’t save a life while it’s sitting in a refrigerator. It’s really painful to open that fridge and have doses sitting there, and think you’ll just take them out and put them in another fridge because of some process,” she says.

Later, health officials told Sharma that excess vials could be used for the next group of patients in the state’s priority list. And, at the last minute, they said she could accept appointments from across the state. They began directing traffic to her website. She watched the slots fill up between midnight and 1 a.m.

Many of the new takers came from Worcester, about 30 minutes away by car. Dr. Michael Hirsh runs a vaccine clinic at the Worcester Senior Center. He says things are going well so far, except he wishes he had more doses. The clinic easily goes through the more than 900 doses it gets from the state each week.

While Sharma was struggling to find first responders in her area who hadn’t yet gotten the vaccine, Hirsh, who is Worcester's medical director, says they were still working their way through fire, police and health departments.

“I think we really have the capacity to give more dosing than we’ve been given,” he says.

It might have been more convenient for his site to receive more doses to begin with and Sharma’s less, he says. After all, Worcester has roughly 190,000 residents, and Webster and its surrounding towns are small.

“I think maybe what has to happen is a little bit more coordination,” he says. “We all know that if we can get our Commonwealth vaccinated, we will achieve a new normal that will get us out of this mess. I just don’t want to see it slowed down by distribution problems.”

The Department of Public Health didn’t respond to questions about how it allocates vaccine doses, but the state has made some adjustments recently. Last week, it opened up appointments for residents 75 and older, and suspended deliveries to hospitals and nursing homes, which already had enough doses for their staffs. The massive health care network Mass General Brigham sent over 3,000 doses of Moderna vaccines back to the state to help with reallocation.

Hirsh says part of the problem may be with the federal government. State officials have complained they get little advance warning about new vaccine shipments.

“They get two days’ notice as to when they’re going to get their next shipment. Then they only have two days to figure out how to divide it up,” Hirsh says. “So, I don’t envy Secretary Sudders, the job she’s had to do.”

Massachusetts Secretary of Health and Human Services Marylou Sudders oversees the state’s COVID-19 vaccination program. It is the largest and most logistically complex public health operation in a lifetime, says Ben Linville-Engler, the director of MIT’s System Design and Management program.

“At the scale with which we’re trying to do this, and the speed with which we’re trying to do this — there’s nothing easy about this,” he says. “There’s a lot of logistical complexity to the vaccine and vaccination, and [health officials] have been working to respond to the crisis for a year. I don’t think that’s an excuse, but they’re stretched from a resource standpoint.”

There are things that would help the program run more smoothly, he says. In particular, flexibility and better guidance for clinics on how to use up extra doses, such as those leftover when people miss appointments or the amount of vaccine doesn’t line up with the number of sign-ups.

“What is an acceptable contingency – so that you’re not wasting doses you have, or losing time and not vaccinating people because you have to send doses back. I think some clarity around those situations would help a lot,” he says. “And there should be a standard answer of how to navigate that situation.”

Now that Massachusetts has opened vaccines to seniors 75 and older, Dr. Sharma is finding it easier to fill appointments at her weekend clinic. But communication from the state can still be confusing. Last week, for example, health officials told her she would receive zero doses. Then, she got an email saying she was confirmed for 400, and later she was told they would be sending 700 doses.

“It’s like a really, really bad game of telephone," she says. "Every time you talk, the story’s different, and you don’t know who to talk to.”

Sharma says she appreciates the massive logistical challenge and the work health officials have done – but the confusion is part of what’s slowing down the vaccination program. If the rollout continues like this, she worries that new variants with the ability to get around the vaccine's defenses become more likely.

“I’m not sure how you can move things fast," she says, "and how you vaccinate a population before the virus mutates this way.”

This segment aired on February 4, 2021.