Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

Language, Socioeconomic Barriers Make Getting Shots To Vulnerable R.I. Residents ‘A Marathon, Not A Sprint’

Resume

Filiberto Paredes first heard about the coronavirus vaccines on the news.

“Pregunté a la doctora si podía ponérmela. Me dijo que no, que tenía que esperar un poco. Seguí insistiendo.”

“I asked my doctor if I could get it. She told me no, that I would have to wait. But I kept insisting.”

He called Anna Delgado, a community health advocate in Rhode Island with the Providence Community Health Centers, months ago.

“At that point, we didn't even have the vaccine. So I said to him, ‘We don't even have it because the frontline has not even gotten it.’”

She put him on the clinic’s list to get a vaccine.

It would take three community health workers scheduling multiple rides to get him in the door.

Filiberto is 76 and lives alone in Providence.

In his majority-Latino zip code, one in six people has tested positive for the coronavirus. And Latino Rhode Islanders have been hospitalized and killed by the virus at higher rates, and at younger ages, than white residents.

State health officials named Filiberto’s zip code as one of the priority areas for vaccine distribution. And in mid-February, the health department gave 100 doses to the Providence Community Health Centers for their patients.

“So there were about 10 of us calling patients all day on Thursday, Friday, and then on Saturday morning, as well,” said Chelsea DePaula, who manages the organization’s team of community health workers.

Filiberto was one of the patients they called.

“La trabajadora social mía me hizo la diligencia para darme esa transportación."

“The social worker coordinated so I could get transportation.”

At 10 a.m. on a recent Saturday, patients started showing up at the Chafee Health Center, which sits just a block away from the industrial Port of Providence. Some came with walkers, others on the arm of a child or caregiver.

After checking in, they took a seat in the long, windowed hallway. Nurses flitted back and forth, offering help with permission forms, answering questions, and calling patients back to the three vaccination stations.

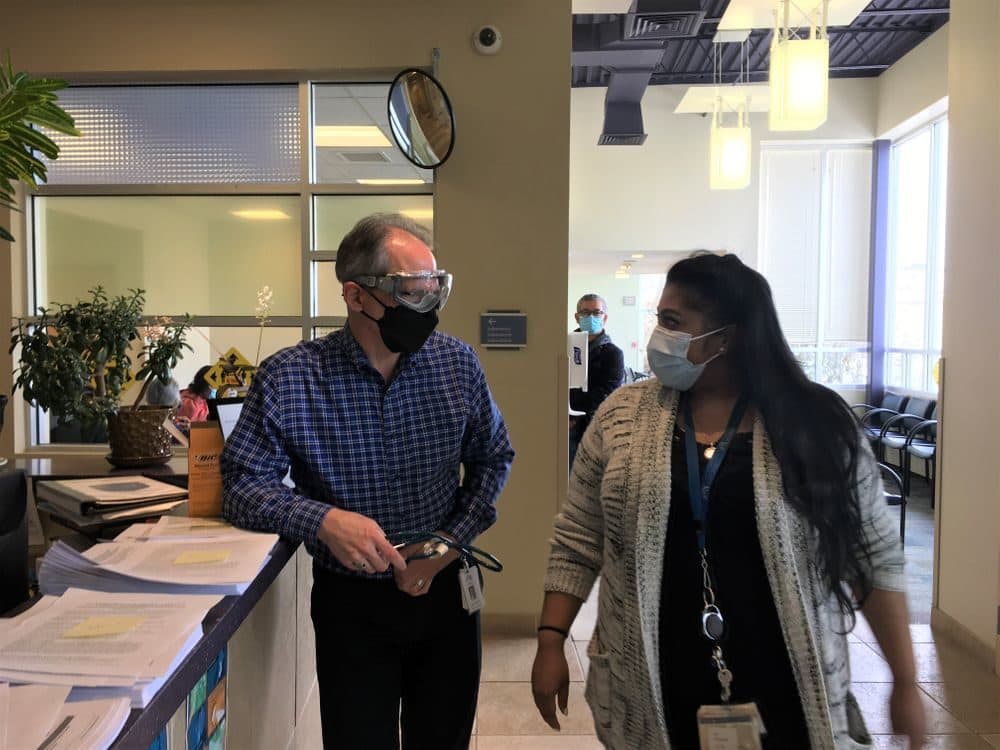

After a quick jab, patients headed back to a waiting area, where Dr. Andrew Saal, the health centers’ chief medical officer, was keeping watch.

In the early afternoon, he got an email that mentioned that a patient was having trouble getting to the health center. It was Filiberto. He’d missed his ride. One of the staff had called him to try talking him through using a map application on his phone instead.

The doctor went to check to see if he’d made it in for his appointment.

“And then Dr. Saal called me and was like, 'Chelsea, that patient never showed up,'” said Chelsea DePaula, who was working the phones from home.

She called Filiberto back and scheduled him another ride. And she stayed on the phone with him until he got in the car.

“And then Dr. Saal texted me when he got to the health center,” she said.

“He was actually the last person to get the vaccine that day. The whole staff stayed after. Like, the clinic was supposed to end at 2. And I don't think he got there ‘til like 2:45. So everyone waited for him just so he could get his vaccine.”

“And then Dr. Saal made sure that he got in the lift on the way back.”

“It is a marathon, not a sprint,” said Dr. Andrew Saal.

Most of the health center’s patients are low income, and over 90% identify as a racial or ethnic minority. The organization asks all patients whether they need help with food, transportation, housing or legal aid. And they routinely provide care in a dozen languages.

At this vaccination clinic, three quarters of the patients listed their preferred language as something other than English.

“Remember, we’re going for that subset of the population that has language barriers, socioeconomic barriers, transportation barriers,” he said. “These are not the people who, if they got a blast email, could show up at the convention center and participate in a mass campaign.”

He said PCHC will soon be receiving vaccines directly from the federal government —part of an effort to get vaccines to low income areas and communities of color. The organization plans to vaccinate at six neighborhood clinics.

Medical anthropologist Dr. Monica Schoch-Spana has studied equitable COVID-19 vaccine distribution, and said tools like rides, translation and conveniently located clinics are only part of what’s needed to address disparities.

“There is this deficit of social trust between communities of color, or some members in communities of color, and the institutions that are meant to serve them in the middle of a pandemic,” she said. “And that kind of work is different from just jabbing somebody in the arm.”

In Filiberto Paredes’ case, that trust was built by Anna Delgado. She’s the health worker who’s been working with him for about two years.

Anna said Filiberto had missed a couple of appointments, so she gave him a call.

“And I said to him, how about we do this? What about if you just come and you just see the doctor, and then let me sit with you. And then we can talk, let's just talk and then let me know what's going on.”

Filiberto immigrated from the Dominican Republic, and he’s worked butchering chickens and paving roads. At the time he and Anna met, his apartment had no water.

“For him to get water, he had to go to the neighbor to fill up a bucket of water to be able to wash his face.”

She helped him get the water and electricity turned back on, and get his finances in a better place. And she regularly checks in to see how he’s doing.

“So he had lots of needs, and we just dealt with one thing at a time,” she said.

For Filiberto, that kind of help has made a big difference.

“Gracias a Dios y a ella. Me ha ayudó bastante," he said in Spanish. "Yo diría que sin Anna Delgado, yo no sería nadie. Yo le agradezco bastante a Dios y después a ella. Porque se ha empeñado bastante con migo, y por la salud mía también."

In English, that means: “Thanks to God and to her. She has helped me a lot. I would say without Anna Delgado, I wouldn’t be anywhere. I thank God a lot and also her. Because she really cares about me and my health.”

Filiberto was eager to get vaccinated. But Anna says many of her patients have been nervous about getting the shot. She finds little ways to ease their concern, sometimes by talking with a worried family member, or by texting pictures of a clinic to a patient, so they know what to expect. Other times, she says she’ll stay on the phone with them when they arrive for an appointment, to ease their worry that no one will speak Spanish.

“I think the biggest barrier is time. Just giving people the time, giving them your ear, giving them the support,” she said.

“It makes a difference, just a little bit more time.”

Miguel Barbosa provided translation. This story is a production of New England News Collaborative. It was originally published by The Public's Radio in Rhode Island on March 4.

This segment aired on March 5, 2021.