Advertisement

Review

Historical Novel 'Hour Of The Witch' Places A Woman's Will On Trial

“It was always possible that the Devil was present.”

So begins Chris Bohjalian’s “Hour of the Witch” — an historical novel, set in Boston in 1662, that is part thriller and part courtroom drama, leavened with romantic intrigue.

For Boston Puritans, the threat of witchcraft is part of everyday life. This prospect will directly complicate the attempt of one young woman, Mary Deerfield, to escape her horrifically abusive marriage.

Now 24 years old, Mary has been married to Thomas Deerfield for five years. Two decades her senior, Thomas owns a successful mill in Boston’s North End. He is also a mean drunk who verbally and physically abuses Mary, but who has enough feral cunning to treat her politely when others are around. Mary has also become adept at living a double life: to friends and family, she explains away bruises she can’t hide with tales of clumsiness.

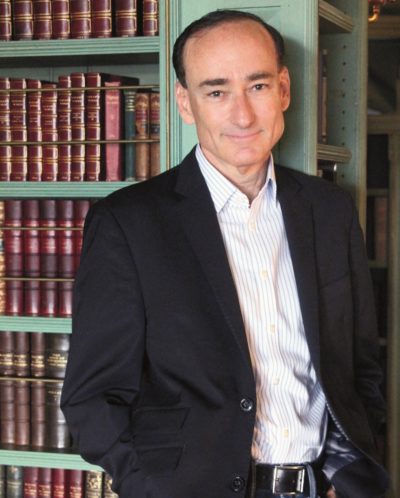

“Hour of the Witch” is wholly different from Bohjalian’s 2020 novel “The Red Lotus,” a plague-related thriller set in present-day New York and Vietnam (written before the COVID-19 pandemic). And that was different from his 2018 novel “The Flight Attendant,” which was made into an HBO Max limited series. Bohjalian, who lives in Vermont, has written 22 books, many of them bestsellers, and many that have been translated into more than 35 languages. His works span an impressively wide range, underscoring a comment he made in a 2020 interview with Writer’s Digest: “…I never, ever want to write the same book twice.”

No matter the subject, Bohjalian often incorporates thorny moral questions that arise from a story’s circumstances, but reach far beyond the boundaries of its time period. “Hour of the Witch” is smartly wrapped in large ideas, like how women must subversively navigate a society in which they have little power, and what a justice system looks like when yoked to a fervent set of religious beliefs.

Advertisement

If her wealthy parents had stayed in England, Mary, blessed with attractive features and a quick mind, would have had an abundance of interesting suitors. But when she was 16, her father had “felt the New World was both a religious calling and a way to build upon an already impressive trading empire.” In this 1660s Boston, religion infuses all actions — for expediency as much as spiritual compass.

As her home life becomes bleaker, Mary feels increasingly distant from her faith. As she sees it, “her Lord God was a mystery and had placed monsters before her.” Though she knows it’s sinful, she can’t help fantasizing about other, kinder, men; particularly Henry Simmons, new to Boston, who shares her more expansive and wry view of life.

A gift from her father inadvertently sets her divorce request in motion: a set of three-tined forks. Although these have become popular in Europe, the colonists are quite content to continue eating with a spoon and a knife. Because of its pitchfork design, Bostonians refer to a fork as “the Devil’s tines.”

Forks may not be the Devil’s handiwork, but they do cause Mary grief. Someone has taken and buried their forks near their door — for what purpose? In one of his rages, Thomas drives a fork deep into Mary’s hand. Fearing that Thomas might eventually kill her, Mary gains a petition for divorce on the grounds of cruelty, and the court proceedings are to be held at the Boston Town House.

In “Hour of the Witch,” Boston is a fast-growing city where modern commerce coexists uneasily with old, fearful ways. Streets and shops bustle with people, and the wharves are crowded with ships that unload exotic fruit and finely-crafted furniture. At the head of State Street stands the Boston Town House, just a few years old. Next to it is the square that holds a whipping post, stocks and a scaffold, “where the deviant were punished by the devout.”

In court, it is primarily Mary’s behavior that is under suspicion. Vague rumors that had been floating in Boston’s judgmental air coalesce into damning witness statements. (She is still childless, after years of marriage. She flouts doctors’ wisdom by mixing her own herbal remedies. She’s been seen visiting that old woman who lives alone out on Boston Neck.)

Tensions build inside and outside the Town House, all in dialogue that Bohjalian has crafted to sound both authentically of 17th-century New England, and remarkably natural.

The court concludes that Mary is more a disobedient wife than Thomas is “unkind” (the comically understated word of one magistrate). She must return to her husband.

Turns out that will not be the worst of her worries. Soon enough, other strange objects are discovered in the Deerfield home. Mary is officially accused of witchcraft, and must now face a new, far more dangerous, trial.

Decades before the infamous Salem witch hysteria, Bohjalian shows just how easily these particular seeds of distrust can be sown. Especially when those in power are unable to see Mary (or any woman), as a full, rational human being. In a novel with much going on beneath the surface, that view may hold peril of its own.