Advertisement

'A Reckoning In Boston' Asks Its Audience — And Filmmaker — To Examine Privilege

Late one night in an adult education classroom in Dorchester, Kafi Dixon compares the toll of living in an environment that upholds white supremacy to a “slow drip, drip, on a hard stone.” Her comment prompts a burst of discussion. One student ups the comparison to a trickle and the group shares a laugh when another adds, “Turn that faucet off!”

Drawn to the intimacy and transformative potential of the Clemente Course in the Humanities -- designed to give adults with limited financial resources a chance to rigorously study literature, history, and philosophy — Newton filmmaker James Rutenbeck thought he’d make a documentary full of scenes just like the one described, inspired by students like Dixon. And in fact, he tried.

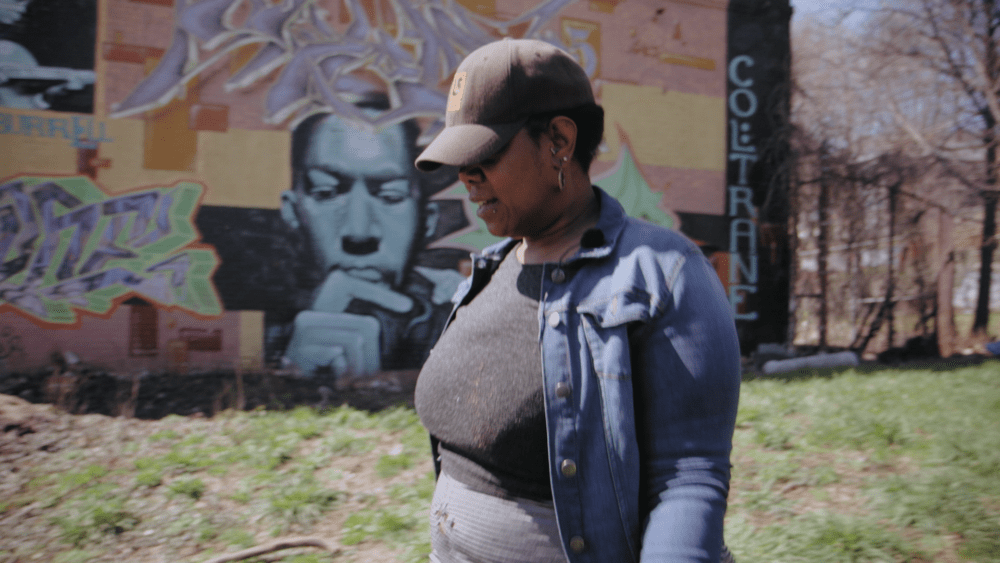

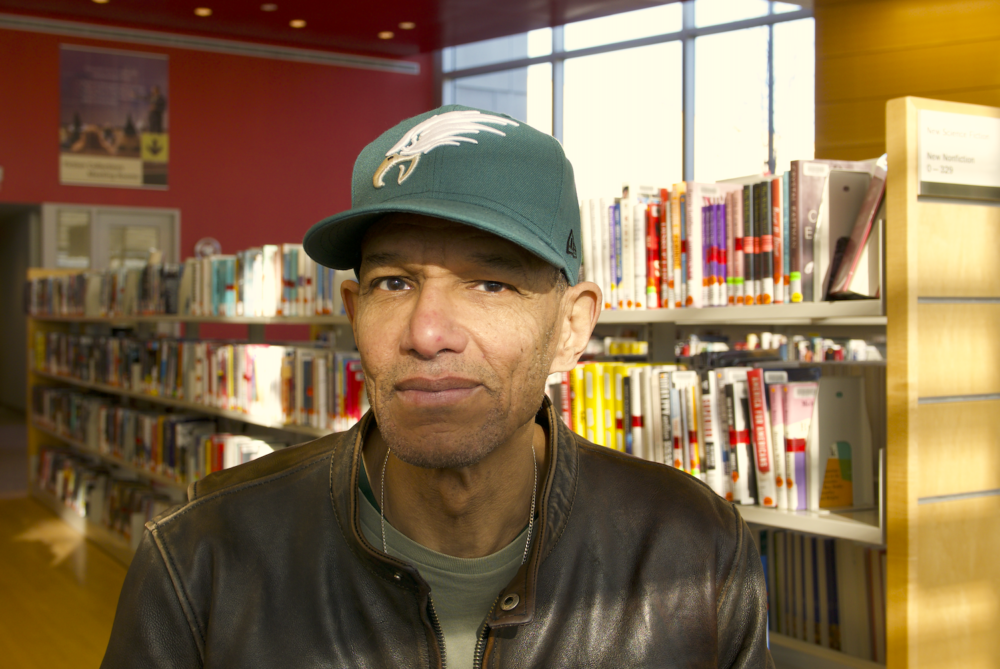

Several years ago he cut together a version that featured Dixon in and out of class — studying Socrates, James Baldwin and more — and turning abandoned Boston lots into vegetable gardens all while facing down the city’s housing displacement crisis and driving a bus for the MBTA. The storyline included Dixon’s fellow Clemente classmate, Carl Chandler, who raised four daughters on his own and had become primary caregiver to his young grandson.

But no matter what he assembled, Rutenbeck (who identifies as white) says the film simply “wasn’t coming together.” He organized rough-cut screenings for colleagues at the Somerville Theatre, then again at Harvard while a fellow at the Film Studies Center. “They didn’t go well,” he says. He had started spending a lot of time with Dixon and Chandler (who identify as Black and Black, Indigenous American and Western European, respectively) and realized he was “ill-equipped to mediate their stories. It began to seem arrogant to try to do it by myself.”

Dixon had a different take on the responses to those early cuts. To her, “The very white audiences had a way of rationalizing our experiences by saying they didn’t understand.” After hearing comments like ‘It was powerful, but I was lost,’ Dixon says she would think, “You’re not lost. You want to be lost. Otherwise, how do you say, ‘I understand this violence, but I have never acted on it.’”

At the same time, Dixon realized that Rutenbeck wasn’t understanding, either, how as a white man he could change how people talked to her and the outcome of a meeting just with his presence.

To that point in his career, Rutenbeck’s award-winning documentary pedigree, earned over a decade as a PBS producer and editor, had tended toward the observational. He studied at MIT Film Section, known for its lineage of personal documentarians from faculty Ricky Leacock and Ed Pincus to their students Ross McElwee and Robb Moss, yet says that in his films, “My intention always was to give voice to [undervalued] people and not get in the way.”

Advertisement

But in this case, he says, keeping his distance “was a way of me protecting myself from me becoming vulnerable.”

At the prompting of ITVS vice president of content, Noland Walker, himself familiar with Boston as a former executive at the production house Blackside, Rutenbeck says he reluctantly started factoring his own relationship to racial and economic privilege into the film.

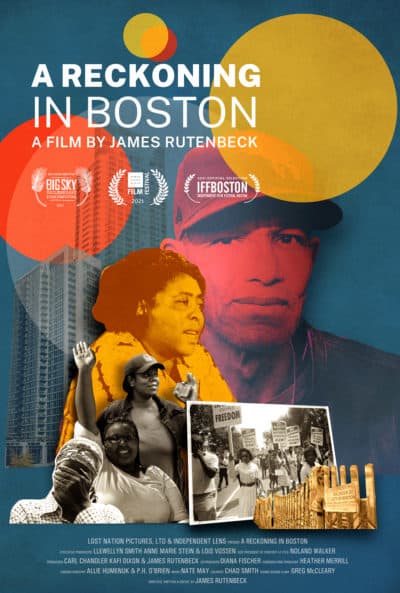

Dixon and Chandler became producers and helped form a new group to give Rutenbeck feedback on a revised approach that added his first-person voiceover. The result, “A Reckoning in Boston,” streaming as part of the Independent Film Festival Boston and slated for a future season of ITVS’ Independent Lens, includes a story narrated by Dixon, Chandler, and Rutenbeck about what it means to come together as a city.

Through the lens of classroom discussions, classic and contemporary texts, scenes from Dixon’s and Chandler’s lives, current statistics, and archival footage that depicts some of Boston’s racist touchpoints over the last century, the film casts a wide net over how and why the household median net worth in Boston could be $247,500 for white residents and $8 for Black residents, for example. (A statistic reported by the Boston Globe that Rutenbeck confesses he thought was a typo.) Because both Dixon and Chandler face eviction within the film, the consequences of Boston’s rapid, exclusive, and widespread real-estate development serve as an urgent backdrop to the many interrelated themes of inequity the film addresses.

“That’s kind of the stake in the ground: the property part, the ownership part,” says Chandler. In the film, he talks about his family’s legacy in New England, one that reaches back to before the Civil War. In addition to his belief in the benefits of the Clemente program, he says that he agreed to participate in the film to have a record to pass down to his children and grandchildren. Despite his daughters earning college degrees and holding managerial positions — what Chandler calls “good jobs” — he says in Boston, “We have sort of limited means for being able to realize the dream of having something of our own.” It makes him wonder, “What’s the minority future?”

A similar concern plagues Dixon, who says she struggles to have faith that Boston can turn things around and become a fully inclusive city. In one of the film’s most gripping scenes, she has a conversation in City Hall where her request to grow food on an open lot is met with one bureaucratic deflection after another.

Processing the barriers that Dixon frequently faces, while making what seem like simple — even noble — requests took Rutenbeck time. “I didn’t understand the dynamics in that room until maybe a year later and after many viewings of it,” he says. After that crucial scene, Rutenbeck appears on camera, this time walking with Dixon to a housing meeting. The cameras don’t enter but his voiceover tells us that a long-unresolved issue quickly resolves in her favor. The reality of his influence makes him sick to his stomach.

Of course, none of the three filmmakers, nor the film they made together, offers easy solutions to overcoming entrenched racial injustices. Yet, avoiding the topic poses an existential threat to Boston, according to Dixon. “This city cannot continue to exist in a bubble that does not interrogate itself,” she says. She has come to terms with the fact that all constituencies must play a role.

“It’s a problem for the city as a whole,” she says. Socrates, it turns out, agrees.

The film is streaming as part of the Independent Film Festival Boston on May 7.