Advertisement

Study Predicts 'Rapid And Unstoppable' Antarctic Ice Melt If Paris Targets Missed

A new study predicts the ice covering Antarctica could start disintegrating much faster in the second half of this century if countries miss the targets laid out in the Paris Agreement. The "rapid and unstoppable" melting could cause global sea levels to rise dramatically, further threatening coastal cities like Boston.

The research, led by University of Massachusetts Professor Rob DeConto and published in the May 5 issue of "Nature," adds to a growing body of science outlining the increasing threat of sea-level rise from melting ice sheets and glaciers.

"Antartica is potentially a major contributor to sea level rise, and that's really what this paper's about" said Phil Duffy, president and executive director of the Woodwell Climate Research Center, who was not involved in the new study. Duffy noted that there are two causes of sea level rise — ocean water expanding as it gets warmer and land ice melting into the sea.

"Decades ago the thermal expansion was the biggest factor, the ice sheets weren't melting very much. Now the ice sheets are melting more and more."

The ice sheets covering Greenland and Antartica contain a vast amount of water — Antarctic ice alone would raise global sea levels by 187 feet if it all melted.

"We don't expect those big ice sheets to melt entirely in the coming centuries," said DeConto, who co-directs the School of Earth and Sustainability at UMass Amherst. Because Antarctica is colder than Greenland, there hasn't been widespread melting or iceberg calving on the southern continent yet. But because there is so much water locked up in Antarctic ice, "even a small change can have really dramatic impacts on our coastlines," DeConto said.

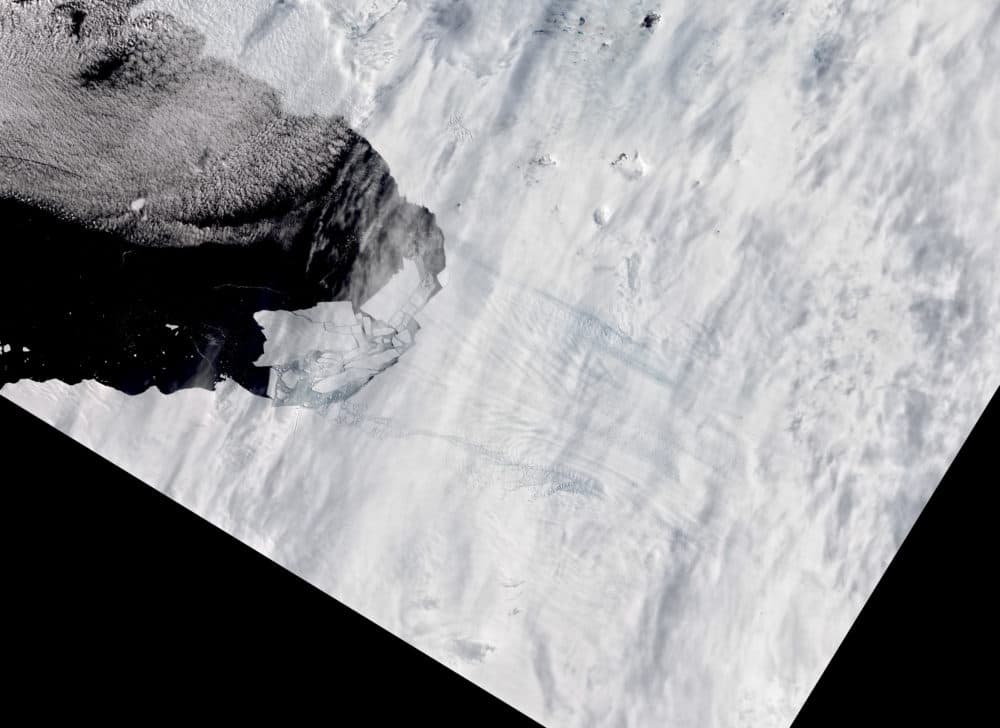

The ice sheets covering Antarctica naturally flow into the ocean, where they form a fringe of ice shelves. The ice shelves are critically important, said DeConto, because they slow the flow of ice and also prevent the edges of ice sheets from collapsing.

But as warming increases, the ice shelves become thin and fragile and can disintegrate entirely. "Once those ice shelves are lost, the ice sheet itself — which holds all of this potential sea level rise — starts to flow faster out into the sea, and in some places might be prone to actually breaking or crumbling," said DeConto.

Advertisement

DeConto's current research examines whether Antarctic ice could reach a tipping point at a certain temperature, when it's so unstable and flowing so fast that there's no way of stopping its demise.

He ran computer simulations basted on the targets laid out in the Paris Agreement, an international accord in which nearly 200 nations — including the United States — have agreed to limit their greenhouse gas emissions. The goal of the Paris Agreement is to keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial temperatures, so DeConto ran his simulations at 1.5, 2 and 3 degrees.

When the simulations got to 3 degrees Celsius, "things changed," said DeConto.

The simulations predicted that Antarctic ice melt could reach a tipping point if global warming hits somewhere around 3 degrees Celsius — about where we’re headed at the moment. At that temperature, "before you get to 2100, instead of contributing about a half a millimeter per year to sea level rise, the rate increases to half a centimeter per year," said DeConto. "So, a tenfold uptick."

That could translate into about eight inches of sea level rise by 2100 from Antartica alone. For comparison, sea-level rise in Boston for the 20th century, from all sources, totalled about nine inches.

Boston currently ranks eighth in the world among metropolitan areas in expected economic losses from coastal flooding, estimated at $237 million per year between now and 2050.

DeConto cautioned that some uncertainty remains around the exact temperature of the tipping point, and notes that other computer models have revealed somewhat less dire findings. But scientists agree that the pace of sea level rise is increasing, and the window for action is closing.

"There's still uncertainty and that uncertainty is important," said DeConto. "We want to reduce that uncertainty because that tells us really how much time we have left before we get our act together and really aggressively begin reducing emissions."

"The big message is that there is a tipping point in these processes of physical disintegration," said Duffy. "It's not a great plan to say, 'Oh we're gonna let it warm up to 3 degrees and then cool it back down,'" because sometimes there are irreversible consequences."