The Pandemic Left More Kids Feeling Suicidal. One Mass. Teen Found Her Way Out Of The Dark

When schools first shut down last year, Marie saw it as an extended vacation.

She didn't like school much. But cooped up with her parents and four siblings at home in Worcester County, she started to feel like she couldn't breathe.

"The longer the lockdown got, it wasn't just, like, the doors — like, the physical doors," Marie said. "It felt like there were doors, like, around me closing off."

She was 16 at the time and already struggled with depression.

We're identifying Marie by her middle name, and omitting her mother's name, because Marie doesn't want her peers to know the details of her mental illness. Her mom fears her story being public could hurt Marie's future career chances.

Marie says it hurt to see others getting depressed in the pandemic. It seemed as if the world around her was falling apart, like she was.

"I was just in myself all the time. And it showed, because my ability to, like, be around people and interact with people got so much worse," she explained. "I've always had social anxiety. But this was to the point where I couldn't be around people and not lose it ... or just break down and cry."

It became difficult to communicate with friends. She lashed out at the one close friend she had, and the relationship ended.

"Losing her made it feel a lot worse. And then I was angry at myself," Marie reflected. "And the depression I got set into due to COVID made me so aggressive towards other people."

Her mother says it was extremely difficult to navigate Marie's explosive moods.

"Some of the things that she came out with, I couldn't believe that she would even vocalize those things," her mom said. "They were so mean."

Advertisement

Life at home was worse than at any point since her daughter's mental illness had emerged several years earlier, Marie's mother recalled. There had been a suicide attempt in 2016 and some impulsive, dangerous episodes. But now, Marie's depression and anger were hurting the whole family.

"My 4-year-old had to learn a whole new sister," she said. "She went from someone who was really a companion, and someone who helped him and took care of him, to someone that he couldn't count on or turn to. ... And so he kind of lost that relationship. I feel bad for him."

Spiraling Downward

Marie knew she couldn't continue hurting other people.

"I had always been a person who, yeah, they destroy themselves," she said, "but I had never been a person who destroys everyone around them, too."

She reached a breaking point last September and attempted suicide. But she quickly realized the gravity of what she had done. She told her mother she needed to go to the hospital.

"I remember being in the ambulance, and the EMT just held my hand and told me how much I mattered to someone and that they would never want me to die," Marie recalled. "And it felt like the one thing I needed to hear to just keep going until I could get the help, the medical help that I needed."

"I remember being in the ambulance, and the EMT just held my hand and told me how much I mattered to someone and that they would never want me to die."

Marie

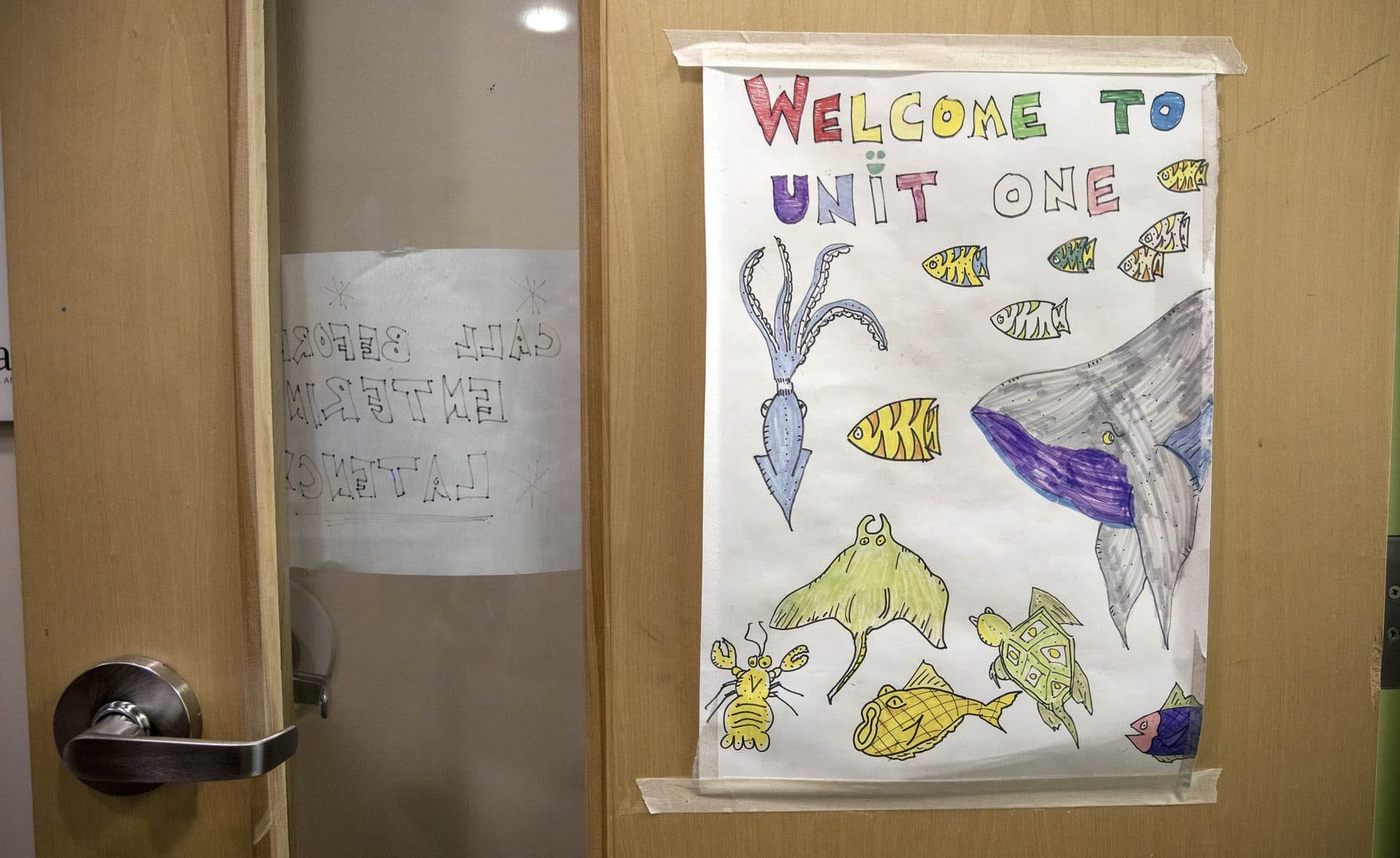

She spent most of the next three months in psychiatric hospitals, where it was hard to escape the stress of the pandemic. At one point, she said, a staffer tested positive for the coronavirus; she and other patients had to quarantine in their rooms. One of her roommates, who suffered from depression, was terrified.

"She was crying when she found out we were locked down in our room, because she was afraid if she did something to herself, no one was going to be able to find her and help her," Marie recounted. "I used to lay awake at night listening to her breathe, to make sure something didn't happen."

For Youth, An Increasing Risk Of Suicide

Cases like Marie's have become more prevalent in the last year. Some children's hospitals have documented significant increases in kids who need help for suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Franciscan Children's in Brighton said in the year after the pandemic started, three-quarters of its patients reported having made a suicide attempt in the prior month — an increase of 32% from before the pandemic.

Boston Children's Hospital documented a 47% increase in kids needing to be hospitalized for suicidal thoughts or suicide attempts between July and October of 2020, compared to the same period the year before; the trend continued into 2021. On a single day last week, Children's said it had more than 40 children hospitalized or awaiting beds for reasons related to suicide.

According to the state Department of Public Health, in March of this year, the number of female youth — up to age 24 — arriving in hospital emergency rooms because of suicide attempts reached an all-time high. Female youth arriving in ERs with suicidal thoughts also reached a new peak in March. That coincides with recent national findings reported by the CDC. But state data show the number of male youth seeking emergency treatment for suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts declined.

Suicide deaths among kids in Massachusetts in 2020 stayed in line with recent years' trends, according to Dr. Jeremy Faust, a Brigham and Women's hospital physician who reviewed state suicide data for research. In that year, 18 kids died by suicide.

The Shutdown Scramble To Help High-Risk Kids

Cambridge Health Alliance is one of the providers in Massachusetts that offers inpatient psychiatric care for kids. Dr. Meredith Gansner, an attending child and adolescent psychiatrist, said even in typical times, the majority of her patients have suicidal thoughts — but over the last year, demand for treatment went way up.

"We always have had issues with getting children into beds in some sort of expedient fashion," Gansner said. "But then when the pandemic hit, it was obvious that that became notably worse."

Some kids had to stay in the hospital longer than expected, because everything else was shut down and their parents had to work.

"I had one child who, I really wanted to send her home, and there was no way that she'd be able to be home supervised. And her school didn't have any sort of hybrid option, even though she was a child with significant psychiatric illness," Gansner explained. "There's no way I could let a child who could become suicidal so quickly to just go be at home by herself, left to her own devices, and her poor mother was just completely stuck."

Gansner says if the state ever shuts down again, certain services — from schools, to mental health day programs, to in-home therapy — should be viewed as essential and remain open in-person for high-risk kids.

"There's no way I could let a child who could become suicidal so quickly to just go be at home by herself, left to her own devices, and her poor mother was just completely stuck."

Dr. Meredith Gansner

Psychiatrist Nick Carson directs pediatric outpatient services at Cambridge Health Alliance. He and other clinicians teamed up to treat patients virtually and help them develop safety plans for when they feel suicidal.

That means asking kids," 'What can you do in the moment to stay safe? Who can you talk to? Friends, parents, trusted professionals?' And that can be tough, because often they say, 'No one. I don't have anyone,' " Carson said. If all else fails, clinicians ask kids what emergency room they're going to go to.

"You know, we just can't avoid that in many cases," he said.

'I Don't Have To Listen To Them Anymore'

Marie hopes to avoid hospitals altogether now. She was discharged in December. The pandemic continued to swirl, and the world still felt out of control. She developed an eating disorder and lost a lot of weight.

But something else happened: she dove into her school work, and she realized she actually liked school.

"It was something I could control, and it was something that would make me feel good," she said. "It could distract me from the world around me that I had high honors in all of my classes. And I would bury myself in work to keep my mind off of depression and COVID."

That newfound success in school — and a TV-inspired fascination with the CIA — led her to research colleges and careers. She started to dream about a future she'd never thought was possible. And she realized it couldn't happen if she were sick and hospitalized all the time. She went back to eating normally.

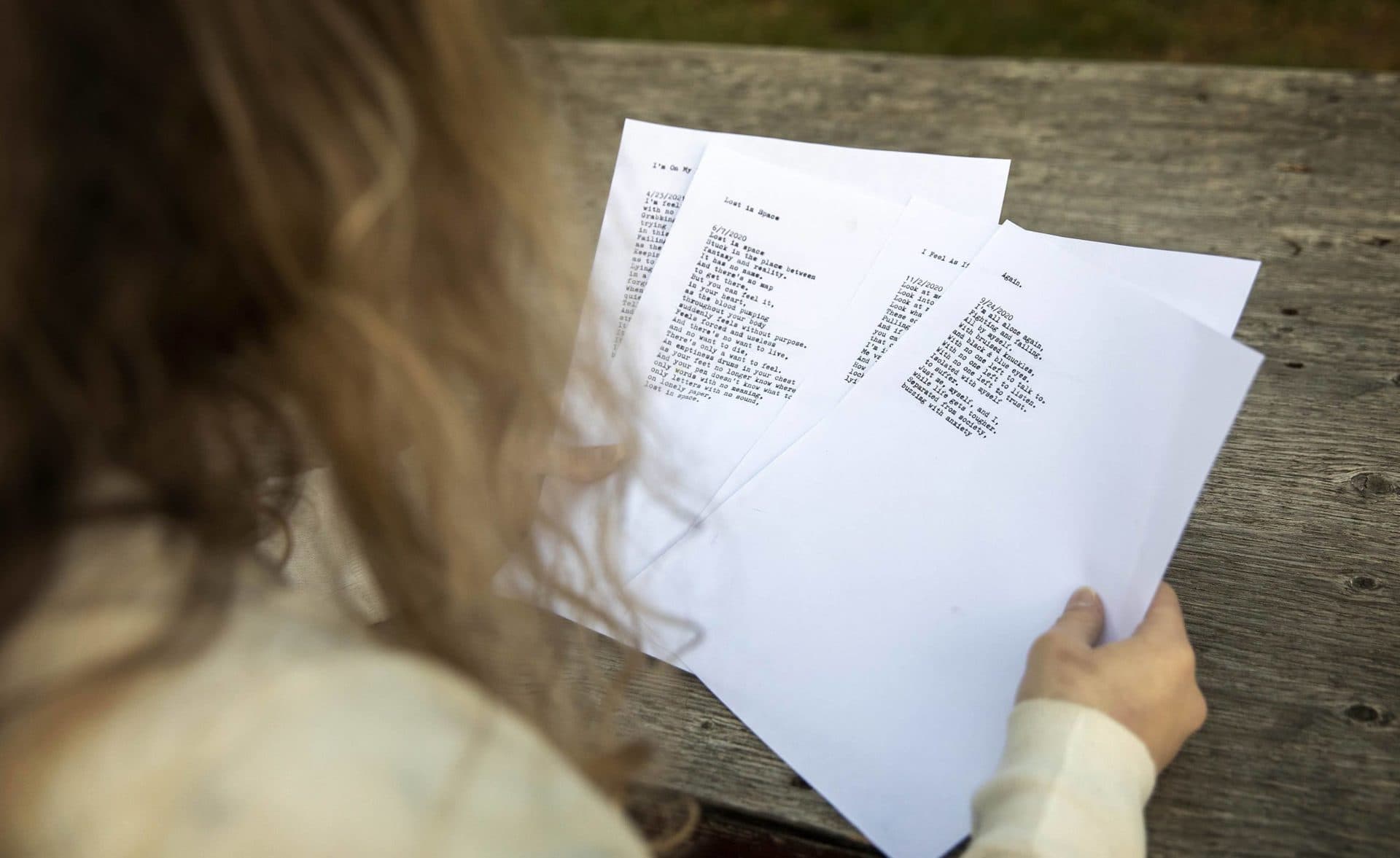

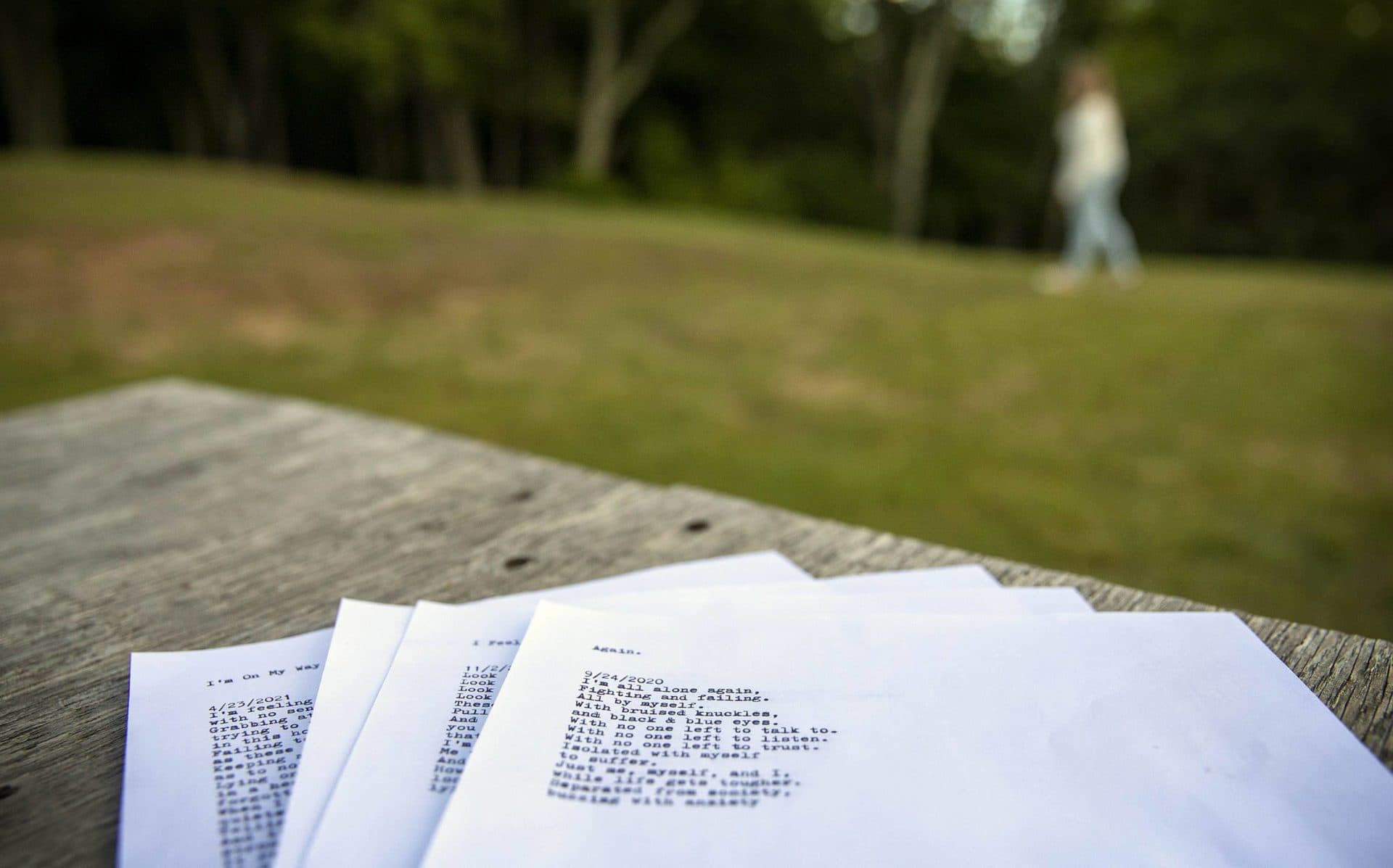

She also writes to help process her emotions, tapping out poems on an old manual typewriter her mom got for her.

... When I hear this little sound

quieter than the others,

Telling me, "It's okay to break down."

And it tells me that I'm brave and

strong enough to get back up.

It reminds me that I matter to someone.

It convinces me to stand and start walking.

It's my own voice.

I have no idea where I'm going,

but I'll figure it out on the way.

Marie believes planning for the future is helping to re-wire her brain. She also takes a new medication that tamps down her impulsiveness, and she sees a therapist. She knows her depression might always trigger thoughts of dying, but she feels the part of her that wants to live is winning. She's realized she doesn't have to listen to her suicidal thoughts.

"And that's what saves me, like, every day, is knowing I don't have to listen to them anymore."

This project is funded in part by a grant from the NIHCM Foundation. Illustrations and animations in this series were created by Sophie Morse.

This segment aired on June 21, 2021.