Advertisement

In Photographer Abelardo Morell’s Italy, Life Upside Down Is Still Beautiful

In Italy, there is a certain combination of magnificence that any ordinary tourist can capture in a casual photo. It is the magnificent, frescoed interior inside a 15th-century palace set in a cobblestoned city surrounded by pine-laced countryside.

But rarely do photos capture all those multiple levels of ravishing beauty and arresting grandeur at once, layered and folded in upon themselves, the way art and genius so frequently are in Italy.

Abelardo Morell’s photographs, on view at the Fitchburg Art Museum beginning Sept. 5 in “Abelardo Morell: Projecting Italy,” are the rare photographs that do just that.

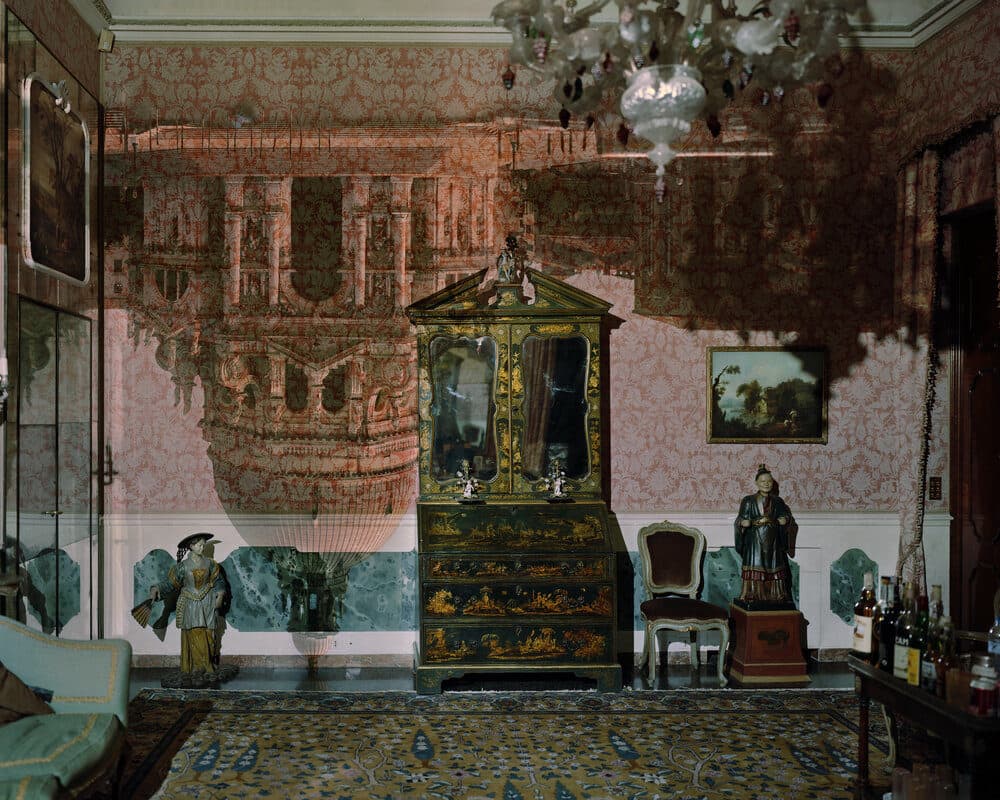

Using the camera obscura technique for which the Cuban-born, Boston-based photographer is known, Morell has reproduced many of the iconic tourist destinations, including the Roman Colosseum, Venice’s Grand Canal and the Florence Baptistery, but in a spectacularly unconventional way mirroring the ingenuity and artistry of his subject matter. About a dozen densely baroque photographs are on view in this show, which runs through Jan. 2 in honor of the 20th anniversary of the Center for Italian Culture at Fitchburg State University.

In one of Morell’s most striking photographs from 2017, “Camera Obscura: View of the Florence Duomo in Tuscany President’s Office in Palazzo Strozzi, Sacrati, Italy,” we see the green and white geometric lines of the marbled Florentine Duomo, projected upside down onto frescoes adorning an elegant Renaissance-era office which is casually littered with signs of the present day, including books and papers. In another, “Camera Obscura: View of Florence from Hotel Excelsior, Italy,” we see Florentine streets and buildings, this time right-side up, projected onto a hotel room wall with a painting whose details we can’t quite see. The shadow of a chandelier, likely made of Murano glass, occupies the center of the frame. In the darkened room, we can also make out a phone, a light switch and an electrical outlet. The colors in the photographs are the traditional hues of a Renaissance painting — terra cotta reds, yellow ochres, deep greens and pale blues. The projection of the street on top of walls and the painting suggests art layered upon art, age upon age, a mix of the ancient and modern, exactly the sensation one gets strolling through an Italian piazza.

Advertisement

“In Italy, you take two steps and you're in the 15th century easily, the layering of artifacts and façades that relate to contemporary and ancient stuff,” says Morell. “I love that sort of transportation back to some older time. But it's all reality. It's not fantasy. It's quite real. And that part is very, very exciting because you don't have to imagine. It’s in the very surface of the buildings that history exists.”

Camera obscura is a tool dating back to antiquity, but it was Leonardo da Vinci who most famously described it in his “Codex Atlanticus” of 1478. It became a popular drawing and painting aid in the 15th century when artists discovered that by pricking a pinpoint hole in a box and allowing light to shine through, they could capture inverted projections of whatever was outside that box. Morell, who was a professor of photography at MassArt from 1983 until 2010, has spent a good part of his long career fascinated with the possibilities of the technique. In his case, he went large — very large — by turning entire rooms into a camera obscura that would become not only the tool but the medium and the subject.

“I made my first picture using camera obscura techniques in my darkened living room in 1991,” he explains on his website. “In setting up a room to make this kind of photograph, I cover all windows with black plastic in order to achieve total darkness. Then, I cut a small hole in the material I use to cover the windows. This opening allows an inverted image of the view outside to flood onto the back walls of the room. Typically, then I focused my large-format camera on the incoming image on the wall then make a camera exposure on film. In the beginning, exposures took from five to 10 hours.”

In those first experiments, Morell was able to create mysterious black and white photos depicting inverted reflections of the Quincy street he lived on. They were disorienting and fantastical, a panoply of order and chaos, reality and surreality, in which bedposts, lamps and chairs danced with upside down trees and bottoms up clapboard houses. Fascinated by the result, Morell took his camera obscura to other locales, including Manhattan where he photographed the Empire State Building in the mid-‘90s, Wyoming where he captured the peak of Grand Teton, and Paris where he photographed the Eiffel Tower.

“One of the satisfactions I get from making this imagery comes from my seeing the weird and yet natural marriage of the inside and outside,” he writes on his website.

In 1999 and 2000 he also ventured to Italy, where he caught images of an upside Pantheon splattered across the walls of a hotel room, the Umbrian and Tuscan countryside and the Santa Croce church in Florence. Those hallucinatory pictures are intriguing enough but are nothing like what resulted when Morell began using color film, positioning a lens over the hole in the window plastic he was using. Suddenly, the photos became sharper, more detailed, luminous. He also began sometimes using a prism to allow projections to come right side up, and he switched to digital technology allowing him to shorten his exposures. Now, his exposures average 2 to 4 minutes and allow Morell to capture moment-to-moment changes in light, clouds, sky and shadows.

Having built a name over the years, Morell receives commissions and invitations, sometimes from other well-known artists, to take photos in breathtaking places.

“It sounds like I'm a wealthy guy, but I'm not,” he laughs. “I have good friends.”

The pandemic temporarily put the brakes on his travel, but not on his art. During the first surge of COVID-19 in 2020, Morell cloistered himself in his Newtonville studio where he says, “I ended up working harder than I've ever worked in my life.” He completed a photo series dedicated to “Alice in Wonderland,” Alfred Hitchcock and another based on construction blocks.

Though his ongoing series on Italy was interrupted over the last year, he is planning to pick it up again when he returns for the eighth time in May 2022. For his next trip, which comes at the invitation of Sol LeWitt’s widow, Carol, he plans to visit Positano and capture images of the Amalfi Coast.

Whatever Morell comes up with next time is likely to pick up on the melodic dissonance so evident in his entire body of camera obscura work. These photographs, intentionally or not, have some of the qualities of Morell’s favorite type of music — jazz.

“I've been a huge jazz fan,” he says. “At one point that's all I thought about. But I like it when certain jazz becomes like polyphony, just like Charles Mingus’ music, where everybody's going at it. It's not noise, but it feels like it's just wonderful, coherent noise.”

“Abelardo Morell: Projecting Italy” is on view at the Fitchburg Art Museum from Sept. 5-Jan. 2.