Advertisement

Review

Series At The Brattle Highlights Early 1990s Black Filmmaking Boom

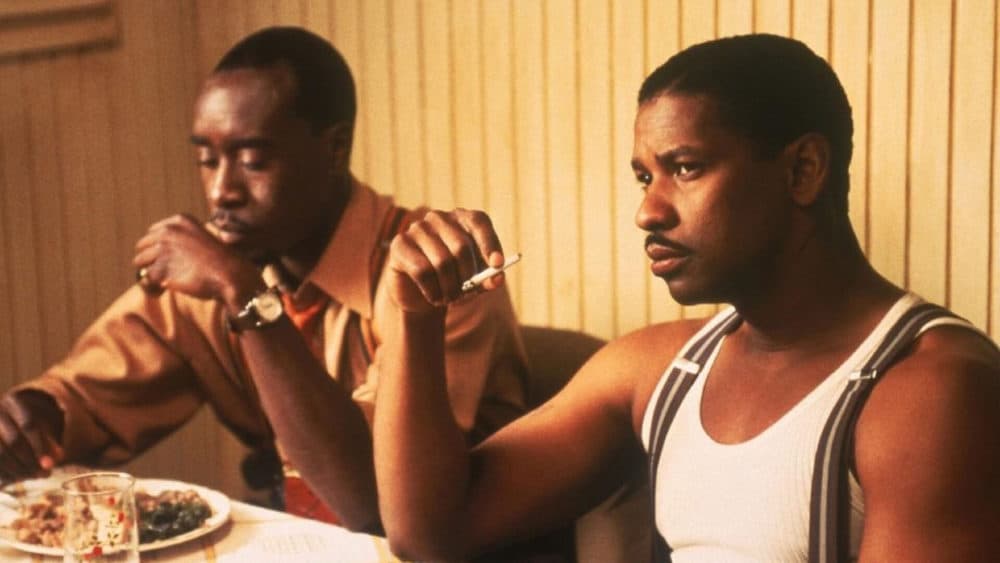

In a cinema landscape where everything’s a franchise, it’s infuriating that we aren’t on our fifth or sixth Easy Rawlins movie by now. Director Carl Franklin’s mystifyingly under-appreciated 1995 “Devil in a Blue Dress” stars Denzel Washington as the smooth South Central private eye of Walter Mosley’s wonderful mystery novels, slyly sidestepping corrupt cops and blackmailed politicians with the help of his slightly psychotic sidekick Mouse (Don Cheadle) in a heavily segregated postwar Los Angeles. You couldn’t pick a better movie to kick off the Brattle Theatre’s “African-American Neo-Noir” series this weekend, a collection of four terrific pictures from the early 1990s Black filmmaking boom that brought issues of race to the forefront of twisty, throwback crime stories. Classic noirs from the ‘40s and ‘50s reflected and amplified the anxieties of traumatized men returning to a changed America after WWII, whereas these ‘90s counterparts applied that sort of doomy, old-fashioned fatalism to structural social injustice. It’s a cozier fit than a lot of audiences at the time might have been comfortable with.

The lushest of the quartet, “Devil in a Blue Dress” showcases Washington in fine, fast-talking form as a laid-off factory worker hired to find the missing girlfriend of a mayoral candidate who, we’re informed by Tom Sizemore’s bulky, insinuating fixer, has “a predilection for the company of Negroes.” A marvel of costume and production design, the movie brings classic Hollywood glamour to nightclubs and neighborhoods that never would have been permitted onscreen back when the film takes place. Director Franklin luxuriates in old-school techniques like a retro voice-over and lap-dissolve montages, making “Devil” look and feel like a film that could have been made in 1948, except of course for all the bad language, blunt sexuality and Black people.

Cheadle’s silver-toothed Mouse and his hair-trigger temper loom so large over the movie I always forget he doesn’t show up until an hour in. It’s was the actor’s first big film role, coming off parts on “Picket Fences” and the ill-fated, Bea Arthur-less “Golden Girls” spinoff “The Golden Palace,” and a star was born overnight. (Not a lot of performers can steal scenes from Denzel Washington, let alone an entire picture.) Their crackling chemistry is just one of the film’s abundant pleasures, as Easy expertly navigates his way through two very different worlds where Black and white dare not intersect without disastrous consequences. It makes me crazy that Mosley wrote 13 more of these books but Washington’s making sequels to “The Equalizer” instead.

A longtime TV actor who came up through the Roger Corman school of no-budget genre filmmaking, Carl Franklin had made a stir three years earlier with “One False Move,” an elegantly understated, white-knuckle suspense thriller that’s not-so-secretly about culture clashes and the color line. Originally slated to be sent straight to video, the film wound up receiving a theatrical release thanks almost entirely to the tireless televised cheerleading of critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert, the former naming it his favorite movie of 1992. (As a teenager, I made my first trip to the Coolidge Corner Theatre, schlepping an hour on the T from faraway Melrose, to see “One False Move” because Gene and Roger wouldn’t shut up about it.)

After a brutal drug murder in Los Angeles, three fugitives — including a pony-tailed pre-“Sling Blade” Billy Bob Thornton, who co-wrote the script with Tom Epperson — are headed for their podunk hometown of Star City, Arkansas, where they don’t know two LAPD officers are already lying in wait. The city slickers have enlisted the assistance of Star City’s back-slapping local sheriff, Dale “Hurricane” Dixon, an amiable rube of boundless enthusiasm played to perfection by Bill Paxton. Primarily known at the time as peckerwood comic relief in the films of James Cameron, Paxton was killer casting because of how the revelations of “One False Move” allow both the character and the performance to deepen and upset our expectations, before ending on a moment of enormous emotional power.

The protagonist of Michael Tolkin and Henry Bean’s screenplay for 1992’s “Deep Cover” was originally written as a white man, but looking to cash in on surprise blockbusters “New Jack City” and “Boyz n the Hood,” the folks at New Line Cinema cast Laurence Fishburne (back then still billed as Larry) in the lead and hired director Bill Duke to fashion the story into a nouveau Blaxploitation capitalism critique, steeped in the shadows of 1930s expressionism and a cheerfully decadent, amoral atmosphere. (The film’s recent canonization by the Criterion Collection is well-deserved but I worry might lend too much of an academic air to the presentation of what works best as a rotgut crime picture.)

Fishburne stars as an idealistic rookie recruited by a rotten DEA agent (an amusingly against-type Charles Martin Smith) for a not-exactly-legal undercover assignment, during which he teams with Jeff Goldblum’s deliriously sleazy criminal lawyer on a designer drug scheme. Like Franklin, Duke started out as an actor. His scary screen presence was a staple of ‘80s action movies, usually the second or third to last guy the hero killed before moving on to the main antagonist. Duke made his feature directorial debut the previous year with an adaptation of Chester Himes’ “A Rage in Harlem,” clashing with producers over the picture’s tone. Released two weeks before the LA riots, “Deep Cover” foregrounds the scenario’s smoldering racial resentments, with Goldblum giving one of his most lip-smacking, fearlessly funny performances as a child of privilege obsessed with all things ebony. His fixation on Black culture is presented as increasingly vampiric, until by the end he’s dressed like Nosferatu.

The lone box office hit and perhaps most preposterously entertaining of these films closes out the series on Sunday. “Set It Off” stars Jada Pinkett Smith, Vivica A. Fox, Kimberly Elise and Queen Latifah as four janitorial workers turned bank robbers in this smash-and-grab melodrama from director F. Gary Gray. What’s so much fun about the film are all the ways in which screenwriters Takashi Bufford and Kate Lanier update traditional “women’s picture” tropes for contemporary concerns, complete with a hunky banker boyfriend for Pinkett Smith played by Blair Underwood like a love interest from a 1950s Doris Day movie. The genre-hopping goes meta when these women sit around a conference table in an office they’re cleaning and plot a robbery, talking in Marlon Brando accents while Nino Rota’s music from “The Godfather” plays on the soundtrack.

It’s easy to see why “Set It Off” became a sensation (when I worked at a video store it was basically never in stock) and how the inventively staged heist sequences enabled director Gray to graduate from hip-hop music videos and the Ice Cube stoner comedy “Friday” to major league Hollywood action pictures like “The Italian Job” and “The Fate of the Furious.” Latifah is an absolute scream in this, sending up all the era’s uber-macho gangsta rap stereotypes as a lascivious lesbian packing heat. Though sometimes it can get a bit silly, the film nonetheless articulates the anger of the audience that embraced it. One of the women rationalizes to her co-conspirators, “We’re only stealing from the system that’s f---ing us,” which is a sentiment you can see seething through all four of these fine films.

“African-American Neo-Noir” runs at the Brattle Theatre from Friday, Sept. 24 through Sunday, Sept. 26.