Advertisement

Forgotten rock legend ‘Fanny’ takes the Boston Women’s Film Festival stage

Before Sleater-Kinney, Destiny’s Child, The Breeders, The Chicks, The Go-Gos and The Runaways, there was Fanny.

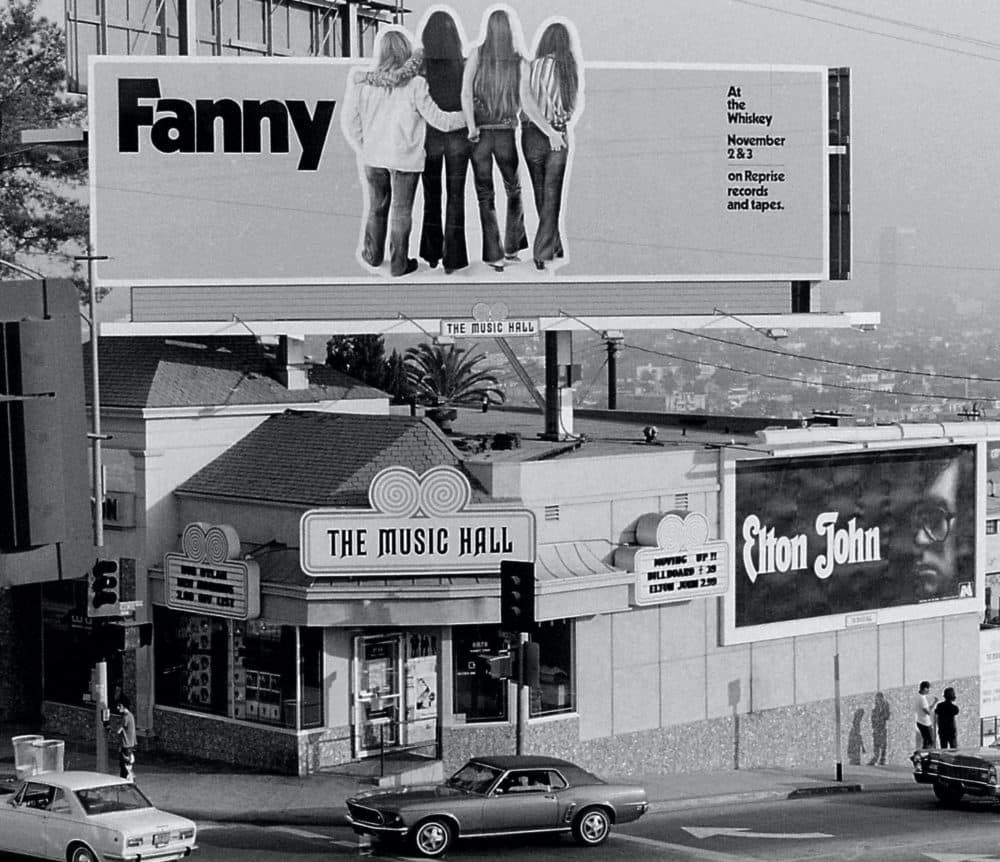

The first all-women rock band to sign with a major American record label, Fanny made five revered albums from 1970 to 1975. But the band’s place in music history has all but evaporated.

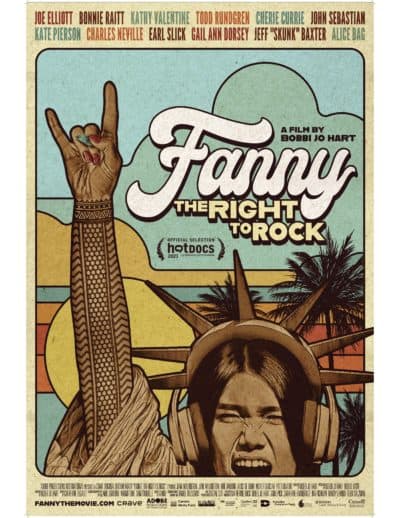

With the new documentary, “Fanny: The Right to Rock,” Montreal-based director Bobbi Jo Hart says she wants to set the record right and put Fanny – and a recent reunion album – back in the spotlight, possibly for good.

On Oct. 8, Hart and Fanny’s lead guitarist, June Millington, will take the Brattle Theatre stage to open the fourth annual Boston Women’s Film Festival. The screening, discussion, and musical performance is the only in-person event for the festival, which runs virtually through Oct. 17.

In addition to its Brattle screening, “Fanny” streams virtually along with five other features and five shorts programs. Festival executive director Jo-Ann Graziano says that resilient women dominate the lineup. The fiction film, “Hive,” for example, about a woman determined to survive in war-torn Kosovo, took Sundance by storm earlier this year while the short documentary, “Point Symmetry,” about two women who connect over parental alienation, has Boston ties. The Boston-made feature “Memoirs of a Black Girl” also streams.

After putting last year’s program entirely online, Graziano appreciates having an in-person event to honor Fanny. “I think it’s important to be celebratory at this time,” she says.

Hart explains that she made the film to rewrite “herstory,” and immortalize a smart, powerful all-woman band. Speaking by phone the morning after a screening in Woodstock, New York, she says she stumbled on the story of Fanny’s formation while shopping guitars online for her daughter. “I saw this photo of an amazingly beautiful woman with flaming gray hair, wielding an electric guitar.” She clicked to learn more about Millington, who also co-founded the Institute of Musical Arts (IMA), a rock camp for girls in Goshen, Massachusetts.

Intrigued, Hart started listening to Fanny’s groundbreaking classic rock tracks. “I was equally amazed and thrilled and equally upset and mad. How come the music culture had not brought them to me?” She called up Millington, who was open to the project. A few years passed. They had a chance encounter at the 2017 Washington, D.C. Women’s March (Hart saw Millington on the jumbotron, right behind Madonna). Hart says that hearing about a new Fanny record deal became “the catalyst for me to want to start filming.”

“Fanny” opens with three women in their upper years, long hair flying in the breeze of an open 1970s convertible. They crank up a guitar-heavy tune with throaty vocals, “Girls on the road/ Girls on the go/ Doing what we do is going to save our souls.” June Millington, her younger sister, bass player Jean Millington, and drummer Brie Darling — all Filipina American and one-time members of Fanny — have gathered to make a new album they decide to call “Fanny Walked the Earth.” In some of the film’s best verité scenes they jam, riff, write, reminisce, rewrite, and record at the IMA studios.

Their reminiscing leads the film back to June and Jean’s 1961 move from the Philippines to California. Family photographs show them as pre-teens, learning to play ukuleles, then switching to guitars for their first all-female band, The Svelts. They describe immediately facing racism in the U.S. and how taking the stage together helped them feel seen, heard, and in charge.

“All of the sudden kids started talking to us,” says June Millington recently by phone. “Music literally saved me.” In the late 1960s, the Millington sisters morphed the Svelts into the cheekily named band Fanny. Hart uses more than 80 photographs taken by bandmates’ friend Linda Wolf to illustrate their unbridled woman power — a tangle of hair, bodies, and a baby — under the roof of Fanny Hill, a house in L.A. that Millington calls, “a sorority with amps.” (Bonnie Raitt muses that her male bassist was disappointed so many beautiful, naked women were gay.)

But with the thrill of free love came the band’s complicated rise at an untenable pace. The film charts how once signed with Warner Brothers, they opened for David Bowie and Deep Purple, played TV shows like Dick Cavett and Helen Reddy, and found special favor while touring in the U.K. Hart pieces the whirlwind together with contemporary reflections from stalwarts like Raitt and footage she uncovered like an ad for tea with Fanny members’ voices dubbed with British accents. She also splices in endless snippets of sexist media coverage that tried to assure readers of the band’s femininity.

Millington says that the male-centric media had the completely wrong idea, and framed the band in what they knew. “Give me a break. We weren’t doing it to flatten the guys,” she says. “It felt great to play like that, like riding a wild horse.” She still wonders, “How could they be threatened so easily? It drives me nuts even now.”

The unwinnable balancing act, and inevitable inter-band tensions, meant that members cycled in and out. (Keyboardist Nickey Barclay, absent from the film and from most public commentary since the band broke up, has cited her own misogyny to explain her distance.) Management’s increasing demands for a “sexier” glam-rock image cued the beginning of the end. The film returns to present-day attempts to get “Fanny Walked the Earth” into the world.

Millington says she lived through important chapters not caught by the film. She met her partner Ann Hackler and together they created IMA. She also became deeply involved in the women’s music movement and wrote an autobiography in 2015. “I’m in my third life. [The documentary] focused on my first life,” she says. The film hints at financial injustices against the band but doesn’t blow any whistles. And the storyline coalesces around an unexpected and emotional (non-COVID) turn that jeopardizes a reunion tour.

Until they saw the film, Millington says even her own friends didn’t realize what Fanny was up against. “People were upset. Pissed. Bobbi Jo got them riled up in the right way.”

With Fanny’s members in their 60s and 70s, the film, recent album, perhaps even their legacy, face one more hurdle of bias. Hart takes the challenge of ageism in stride. “The more we normalize women kicking ass and women aging on screen naturally, the more we’re celebrating it,” she says. “I want the film to be unabashedly celebrating women who are just doing it and being an example.”

The Boston Women’s Film Festival program streams for the duration of the festival, from Oct. 8-17 with the shorts programs accessible through the end of October. Check geo-blocking for the titles that stream outside Massachusetts.