Advertisement

Documentary 'Bounty' confronts colonial death warrants against Indigenous people

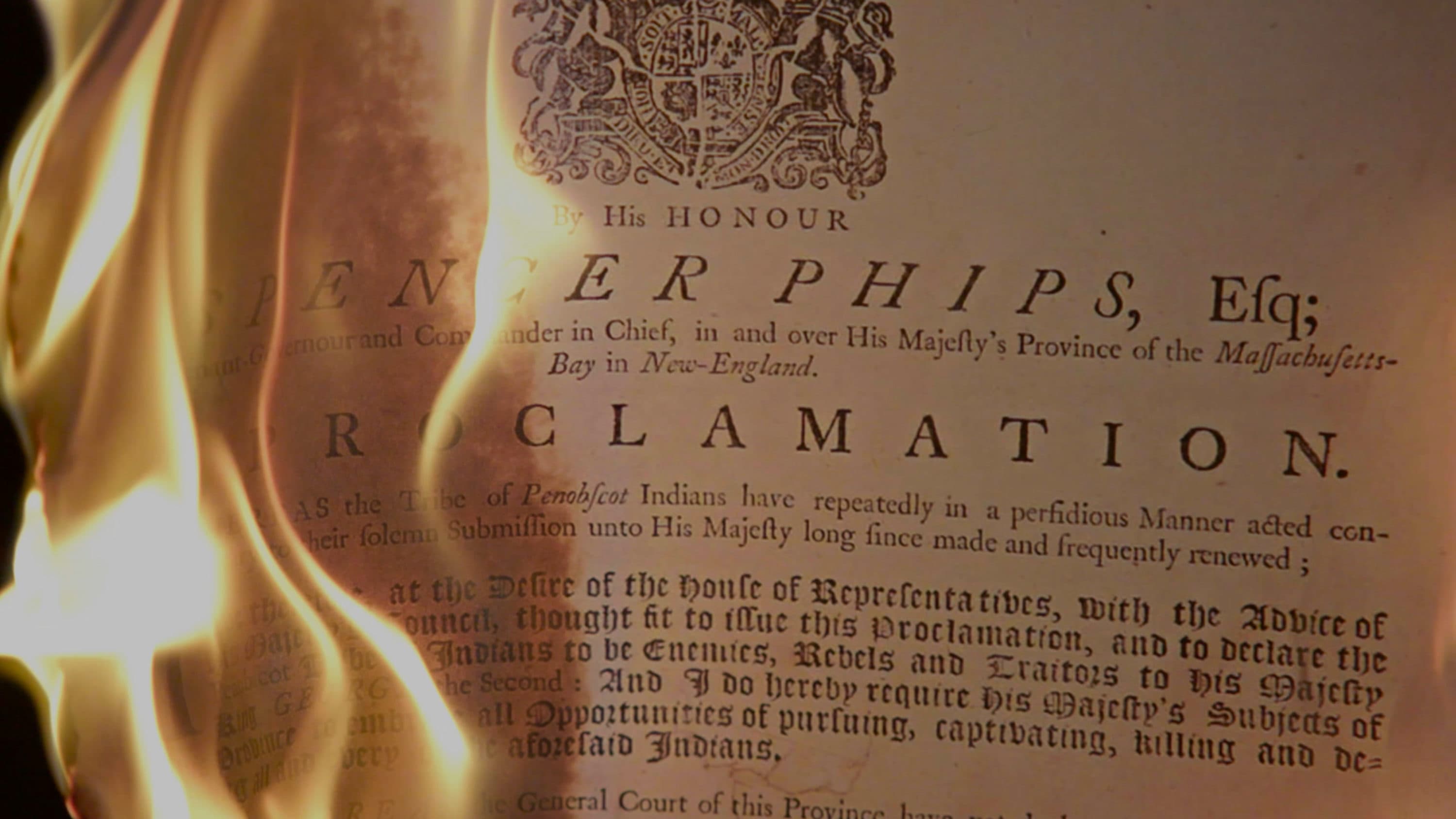

It may be buried history. But the atrocity of colonists’ bounty proclamations against Native American people also occupies the present. In the potent new documentary “Bounty,” members of the Penobscot Nation read one such death warrant to their family members, including their children, in order to share the truth.

The nine-minute film takes place in Boston’s Old State House, where in 1755, colonial settlers signed the declaration of a cash reward, in descending value, for the scalps of Penobscot men, women and children. While visitors might flock to this historic destination along the Freedom Trail, the filmmaking team found that the 69 government-issued scalp bounties in the Dawnland (now called New England) go unmentioned in its exhibits.

Research also revealed that the claims settlers made on those bounties — for at least 375 human scalps with unknown tribal affiliation — translated to millions of today’s dollars and huge swaths of land. Generations of settler descendants have prospered as a result. “For centuries bounties were a license to kill all Indigenous people,” sums the film’s website.

“On a regular basis I run into people who have no idea about what happened on the land on which they currently live,” says co-director and film participant Dawn Neptune Adams. She and her child Kaden appear side by side in the film. She reads a bit from the document and they pause for a delicate conversation, one that serves as an example for how other adults could talk to young people about difficult but inescapable facts.

Adults often fear saying the wrong thing, or teaching the wrong thing and upsetting other parents, acknowledges co-director Adam Mazo. He and educator Mishy Lesser created the Boston-based Upstander Project with the two-pronged goal of educating and mobilizing people against injustice with documentary films. They especially want “Bounty” to reach middle and high school students. “We think there are ways to teach these things without shaming and blaming,” says Mazo.

For years, Lesser and Mazo focused on outreach related to the 1994 Rwandan genocide with their first collaboration, the 2009 documentary “Coexist.” Then Lesser heard a story on WBUR about a truth and reconciliation process in Maine that completely refocused their work. The resulting short film “First Light” (2015), about the government-sanctioned separation of Wabanaki children from their families, evolved into the feature-length “Dawnland” (2018), which spun into the short film “Dear Georgina” (2019). All three, and now “Bounty,” take on the clash of worldviews between Indigenous people and settler descendants.

Advertisement

Lesser has used unlearning her own worldview as fuel for her work. “I didn’t know I was a settler. That I was an uninvited guest on stolen land. That I was carrying so many false narratives,” she says. She has written teacher’s guides for all five films and won an Emmy for her research on “Dawnland.” The “Bounty” guide took three years to create. Lesser also developed and oversees a teacher’s academy. “Every teacher’s guide I write is an attempt to correct my own ignorance,” she says.

That mindset informs the constantly evolving approach at Upstander, says Mazo. “We try really hard to model humility. That it’s ok to make mistakes.” Over time, Upstander has increasingly shifted toward including film subjects as filmmakers. The forthcoming Reciprocity Project and another potentially fictional offshoot from “Bounty” further underscore this direction. A different but connected project, still under consideration, would help non-native people acknowledge their relationship to the settler colonial project.

Neptune Adams made a brief appearance in “Dawnland” and says directors Mazo and Ben Pender-Cudlip wanted her to have a bigger role. But she wasn’t ready. As a child, she says, “being invisible kept me safer.” She grew more comfortable with visibility as she agreed to more and more speaking engagements related to “Dawnland.” That opened the door for her to take on a central role with “Bounty.” (Maulian Dana, who appears in “Bounty,” also co-directed. Though not film subjects, long-time collaborators Pender-Cudlip and Tracy Rector are also credited as “Bounty” co-directors and producers.)

Upstander also accompanies every film with discussions, panels and supporting material online. There’s so much to discover with “Bounty,” including a short video introduction and several independent film clips, they started calling the project a “media ecosystem.”

Neptune Adams appreciates that people have many entry points to the film’s subject matter. She draws attention to the primary resources embedded in the teacher’s guide. “There’s testimony from people who were there, excerpts from witnesses, diaries, treaties, laws,” she says. She suggests that reading it might help with the cognitive dissonance that comes from not knowing — or denying — the history of genocide.

Just as much, Neptune Adams wants those who engage with “Bounty” to see that the scalp proclamations have evolved over time, “from outright murder for money to different forms of oppression, still for money and so-called resources.” She invites those who now live in the land of the Massachusett people to learn about the current struggles of Indigenous people on this year’s National Day of Mourning, what she calls “Thanks-taking.”

Since 1970, the United American Indians of New England have organized an annual banquet in Plymouth to acknowledge the decimation of Indigenous people on what others call Thanksgiving. “There are speakers, a march. It ends with a beautiful ginormous meal,” says Neptune Adams. She would like to see people show up and hear from Indigenous people firsthand.

“The more that we recognize that we are related and connected the easier it will be connected to each other,” she says.

“Bounty” is available to stream online. “Dawnland” broadcasts on GBH World on Nov. 20 at 9 p.m.