Advertisement

Mass. scholars reflect on how Jan. 6 insurrection has affected democracy, racial justice

Resume

The insurrection at the U.S. Capitol one year ago has contributed to lasting questions about the state of our democracy, the weight of disinformation in American society and progress on issues surrounding race.

On WBUR's All Things Considered, we asked three Massachusetts scholars — Ted Landsmark, of Northeastern University; Amel Ahmed, of UMass Amherst; and Ibram X. Kendi, of Boston University — to discuss the ramifications of the Capitol attack and where we are a year later.

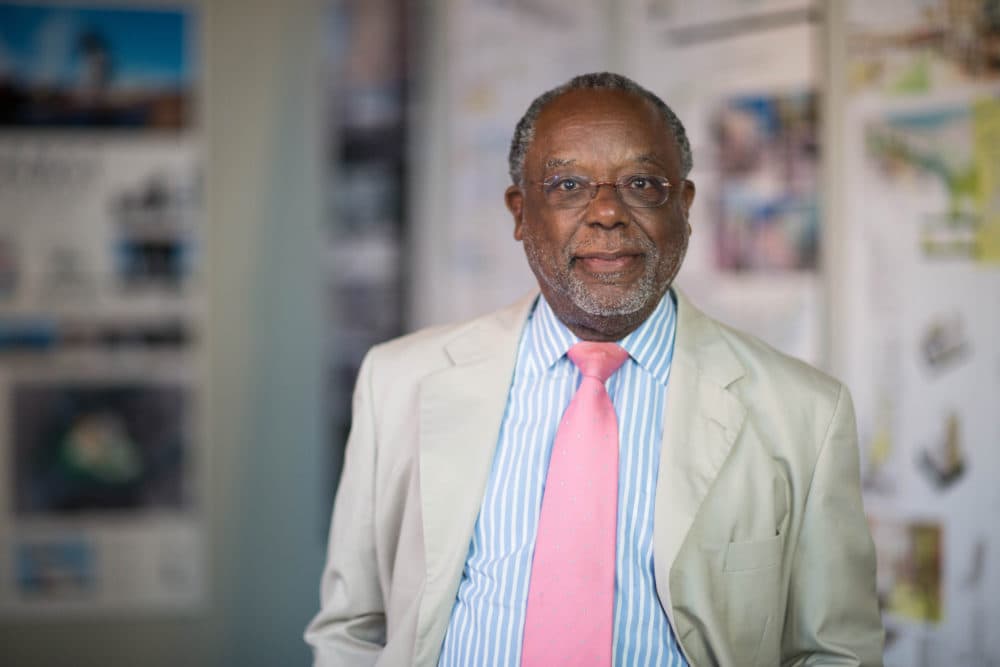

Ted Landsmark

Landsmark is a distinguished professor and director of the Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern. He's a researcher with the university's Institute on Race and Justice and a longtime civil rights activist. He's also widely known as the Black man photographed as he came under attack by a white teen with an American flag on Boston's City Hall Plaza in 1976.

Landsmark was also punched in the face and injured in the incident, which took place during a protest against court-ordered busing and school desegregation in Boston.

On the connection between the assault he experienced and the attack on the U.S. Capitol by white insurrectionists carrying American and Confederate flags:

"The American flag has been used in demonstrations for both honorable and ignominious purposes. When I was attacked by a group of demonstrators on City Hall Plaza in Boston and young people made an effort to kill me with an American flag, an iconic photograph was taken that spoke to the efforts of people of color to achieve equal rights and social progress in this country. And when I, in particular, see the American flag being used for white supremacist purposes, I do more than chafe. I feel as though what the flag should stand for, in terms of democracy, is being demeaned and diminished ... it really is an insult..."

On his overriding emotions about last Jan. 6 and what the insurrection represents in the history of our democracy:

"Jan. 6 really marked an extremely troubling moment in American history because of what it represented for steps back. It was clear, from the presence of Confederate flags and the epithets that were being thrown at Congress people and at security forces, that there was an effort to perpetuate white supremacy and to deprive people who had struggled to achieve equality in terms of voting, of voting rights and civil rights and ... I think that we look back at that moment as the incentive for us to increase our efforts to protect voting rights and to further the cause of civil rights and human rights in the country."

Amel Ahmed

Ahmed is an associate professor of political Science and associate provost for equity and inclusion at UMass Amherst. She says she's spent a lot of time over the last year thinking about cornerstones of our democracy that might be shakier than many people previously believed.

On what's been on her mind related to last year's threat to the transfer of power:

"Why was the peaceful transfer of power in jeopardy? Why do losers accept their losses? What are the conditions that make this possible, and why did we not meet those conditions on January 6? What led up to this kind of confrontation? We did not do a very good job of demystifying the electoral process in anticipation of this election. I think there's a lot of work that still has to be done, because, you know, one of the things I recall right after the election — and still to this day, the phrase that I see over and over again, is that there was 'no widespread evidence of fraud.' But for many people, that phrase is a little jarring. What does it mean that there's no widespread evidence of fraud? Was there any evidence of fraud? Well, why is this OK? And, you know, we shouldn't accept this. So I think that seed of doubt is so easy to plant. What is required is a massive effort to demystify the electoral process and contextualize what we mean when we say that there were some irregularities, but nothing that we should worry about."

On whether the insurrection would have happened even if the communication regarding voting irregularities were clear and thorough:

"I think that's entirely possible. There are, you know, a number of people for whom there's no evidence you could provide that would convince them that this was a legitimate election. And those are not people that I'm going to try to convince. And there are always forces within the political system that would be fine taking power by force rather than through the electoral process. Where I would focus my attention is on the much greater number of individuals who aren't necessarily stuck in that position but have that doubt planted in their head — because that's where you get numbers giving air to these conspiracy theories and giving air to a narrative that really delegitimizes the mechanisms [of democracy and elections]."

On whether she's worried about disinformation becoming a way of life:

"You know, I think it's here. I think it is a worry that there is going to be a splintering of what kind of information people are choosing. But what I would hope, and I believe is still there, is a consensus that this is not how we settle our disputes. If we can reach that consensus, where we just agree that this is just not how we're doing this; we've agreed to certain rules of the game, we're going to follow those rules, because at its core, democracy is an agreement to play the game by a certain set of rules. And when we attempt to veer from those rules, we are always going to destabilize democracy."

Ibram X. Kendi

Ibram X. Kendi is the director of the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research and the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities at BU.

Kendi says he believes awareness about racial divisions and injustices in the U.S. has grown since the Capitol attack, but there's a long way to go.

On what he refers to as America's denial of the role of white supremacy in the country and whether he sees any enduring lessons and positive change in the wake of the insurrection:

"I do think a certain segment of Americans, over the last year and specifically as a result of the insurrection, have recognized, really, the threat of white supremacy. But you know, on the other hand, those who have been subjected to and manipulated by the organizing and ideas of white supremacists don't see them as a threat. If anything, they see them as the solution. If anything, they see people like Donald Trump as the salvation. ... And I think that has led to even further, sort of, division, in which certain segments of America recognize that racism and white supremacy is the problem. And other segments of America imagine that anti-racism and multiracial democracy is the problem.

"What I do know is that in the aftermath of the insurrection, you had both Democrats and Republicans commonly stating that this is not who we are ... when any sort of basic reading of American history will sort of allow us to recognize that this is precisely who we are, but doesn't necessarily have to be who we remain. We can't deny that history, because if we continue to deny it, we're not going to see the threat growing, as it's certainly grown over the last ten years; and then we'll be shocked when it shows itself, as it did on [January 6th]."

On whether he finds himself leaning more toward optimism, fear for the fate of our democracy and progress on racial justice, or both:

"In many ways, I would say a little bit of both. You know, not only over the last year, if not five years, if not ten years, has there been a concerted sort of effort to prevent the emergence of a multiracial democracy, there has been a concerted effort to create that. And people from those different racialized groups have been coming together in numerous sort of ways, recognizing their common humanity, recognizing that we need to create a different type of America that will benefit us all. Even white people will benefit from a democracy, from equality. I think there has been that growing awareness among people. And so that certainly has made me optimistic. ... We have to be incredibly hopeful in order to do the work."

This segment aired on January 6, 2022.