Advertisement

Communities of color get more gas leaks, slower repairs, says study

People of color, lower-income households, and people with limited English skills across Massachusetts are more exposed to gas leaks — especially more hazardous gas leaks — than the general population, according to a new study. Those same communities also experience longer waits to get the leaks fixed.

"There is a disparity. It's consistent. It's across the state. That's a civil rights issue to begin with," said study co-author Marcos Luna, a professor of geography and sustainability at Salem State University. "This is not acceptable."

Study co-author Dominic Nicholas built the database used in the study. Nichols, a program director for the Cambridge-based nonprofit Home Energy Efficiency Team (HEET), had taken the natural gas utilities' records of gas leaks, geocoded them, and made the data publicly available.

"With this large data set finally being geocoded and really high quality, it allowed us to explore the problem at different geographic scales, which was a breakthrough, I think, for this work," Nicholas said.

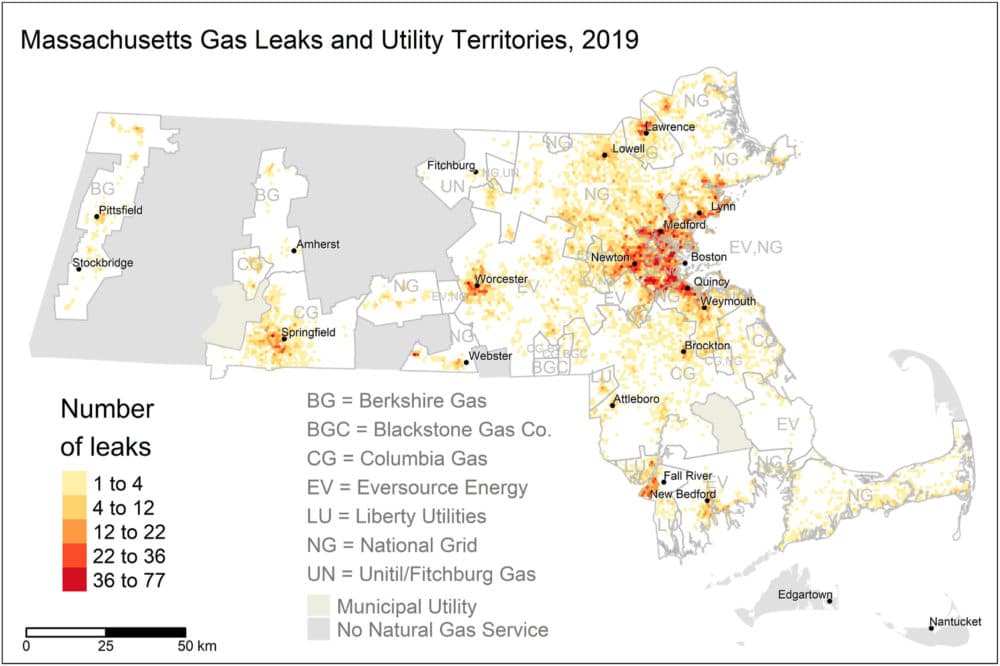

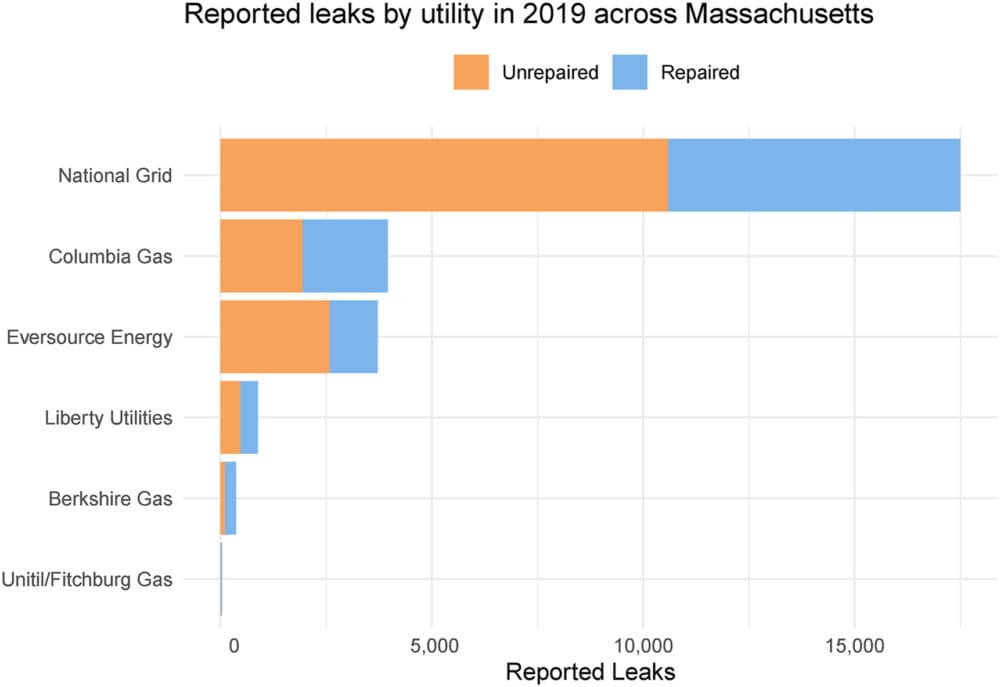

Researchers examined how frequently gas leaks of different grades occurred by community, the ages of the leaks and how quickly they were repaired.

The research revealed that gas leaks don't affect everyone in the state equally; rather, race, ethnicity, English language ability, and income are the leading indicators of exposure to leaks. While there was some variation across the state — for instance, income disparity was a larger factor than racial disparity in the Berkshires — the overall findings held true even in areas of the state with denser populations and more gas pipelines, and areas with older gas infrastructure.

"Massachusetts, despite having a reputation as being a progressive New England state, is still hyper-segregated. So anything that happens on that landscape is going to have different effects on different folks along the lines of race or income," Luna said. "That's the background against which all of our actions take place. So if policies or programs operate in a "race neutral" method, that sounds nice, but can actually perpetuate the problem."

Advertisement

Madeleine Scammell, an associate professor of environmental health at Boston University's School of Public Health, said she found the study "compelling." She said she was especially struck by the fact that some communities had to wait longer for gas leaks to be fixed. That "does have implications for the health of the community and the cost of the community's infrastructure," she said.

About half of households in Massachusetts use natural gas for heat. Gas leaks create fire hazards, degrade air quality, kill trees and contribute to climate change.

Recent research has found that natural gas infrastructure in eastern Massachusetts emits methane — a potent greenhouse gas — at about six times higher than state estimates, and leaks have not decreased over the past eight years, despite state efforts to fix them.

Massachusetts is the only state in the country that requires utilities to report detailed gas leak data, and the researchers said that the federal government should mandate such data collection and reporting nationwide. Luna also said that governments should include environmental justice considerations when developing energy policy.

"That means that you acknowledge that we have an existing problem with inequalities geographically across the landscape and also in the way things work," Luna said. "You have to be proactive in intervening and say, 'We need to worry about how this plays out for those marginalized communities that have been historically left behind.'"