Advertisement

At the Rose Art Museum, painter Barkley L. Hendricks' rarely seen photographs are on display

For most of his career, Barkley L. Hendricks was famous for his arrestingly vivid paintings of people of color, modeled after the regal portraiture of European court painters.

Nobody knew much about his photographs.

But the truth is that Hendricks — the virtuoso painter known for bold life-size portraits of both himself and others — did take photographs. And they share a lot in common with his paintings, including expert composition, a deep interest in fashion, a masterful eye for color, and an unerring capacity to capture mood while making sly social commentary. While some of his photographs served mostly as studies for paintings, others were conceived as stand-alone works of art to be admired in their own right.

Now, in “‘My Mechanical Sketchbook’ — Barkley L. Hendricks & Photography,” opening Feb. 10 at the Rose Art Museum, we finally get a chance to see this other side of Hendricks’ oeuvre, including Polaroids, photographs and never-before-seen works on paper, all discovered in the artist’s New London, Connecticut studio after his death in 2017.

“They provide a deeper view into not just his art, but his vision and his life and his ways of seeing and ways of being in the world,” says Gannit Ankori, Rose director and chief curator who co-curated the exhibit with Elyan J. Hill, guest curator of African and African diaspora art.

“In the photographs, Hendricks gives us a chance to see the world as he sees it, without the same level of manipulation as the portraits,” says Hill. “The photographs become a different invitation into his intimate and interior life than the paintings.”

It was after the Rose acquired one of Hendricks’ self-portraits in 2021, featuring the artist wearing a big black hat, that the museum began to think about doing a broader show on Hendricks, a much beloved African American artist who has inspired subsequent generations of African American portrait painters, including Amy Sherald and Kehinde Wiley.

“He really didn’t use the categories and hierarchies that Western art employs, thinking that a Polaroid or photograph is less than a painting which is less than a drawing,” says Ankori. “He did all these things together. And so, this full picture of his creative genius really is something we have the opportunity to showcase.”

What’s on view is about 65 or so works that juxtapose the many facets of Hendricks’ creative output, with a special emphasis on the photography he referred to as his “mechanical sketchbook,” a quick way to capture those unique visual moments that might otherwise get lost in the fray of daily life. The show is divided into seven groupings, including self-portraits, portraits of others, photographs centered on fashion, technology, and finally, Hendricks’ photographs documenting his experiences living as a Black man living in a racist society.

It was after a 1966 trip to Europe that Hendricks found himself profoundly inspired by the portrait paintings of old masters like Velázquez, van Dyck, van Eyck, Rembrandt and Caravaggio. But missing at del Prado, the Louvre and the Vatican Museums were paintings centered on Black life. From that moment, Hendricks understood his mission to be that of bringing all the grandeur of a Velázquez painting to the people he knew and saw around him. He began a series of portraits, both photographed and painted, featuring Black folk.

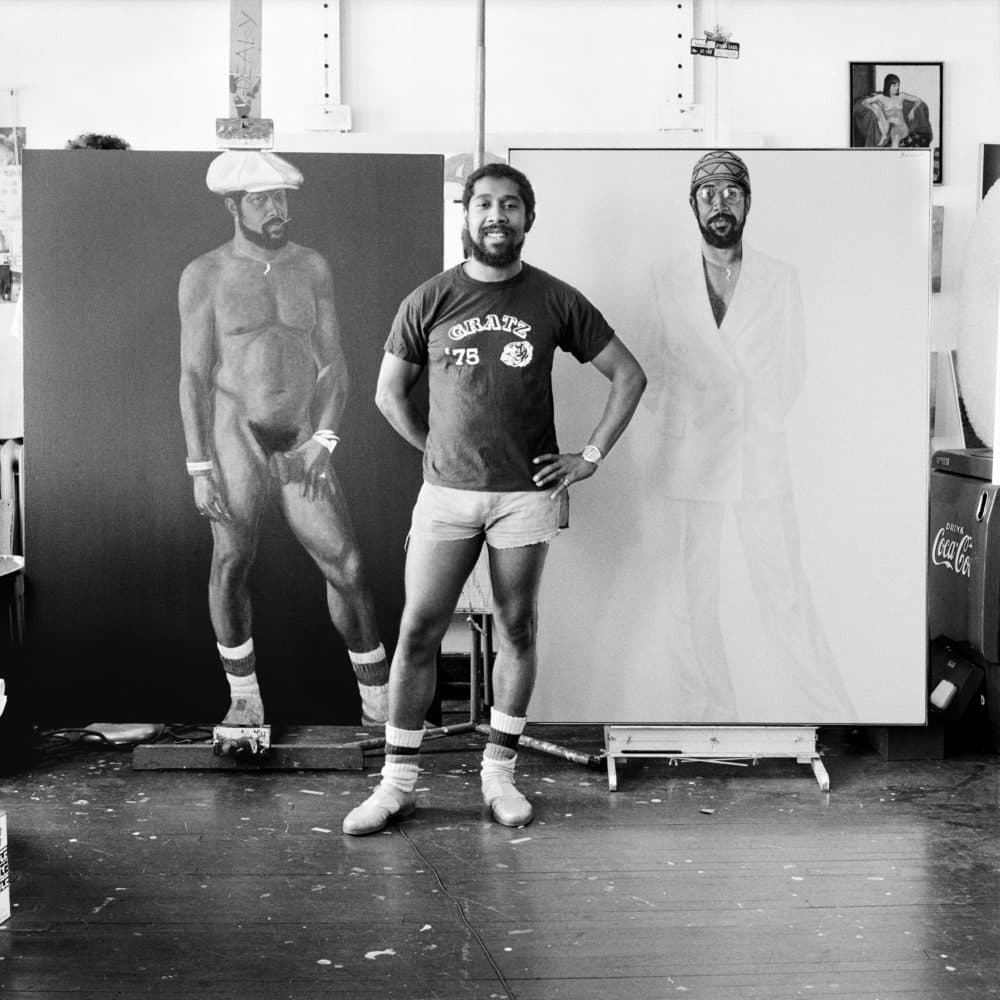

In this exhibit, we see a “triple” black and white self-portrait of Hendricks in which he stands photographed before two of his life-size painted self-portraits. One painting, “Slick” features Hendricks clad in an elegant white suit before a white background . The other features him nude before a flat black background and is entitled “Brilliantly Endowed.” Both paintings, painted in 1977, are Hendricks at his wry best, working on multiple layers.

“It's humorous because the term was taken from Hilton Kramer's review of him that said that as a painter, he was brilliantly endowed,” says Ankori. “But it also had a connotation of the hyper sexualization of Black men, which is no laughing matter. So, I think that he reclaims his own body and the right of a Black body to be desired, to be beautiful, to be naked, to be represented as a full human being.”

“Slick” was painted in response to a playful remark by Hendricks’ sister. “You think you’re slick,” she told him. “Just wait. One day a woman is going to straighten you out!” The painting of Hendricks wearing an African kufi hat in a fashionable white linen suit on a white background could serve as a metaphor for a Black artist making his stylish way in a white-on-white artistic, economic and political environment. Both portraits, says Hill, embody “the cool,” a West African and African American aesthetic that puts a premium on maintaining balance and calm.

“The triple self-portrait of Hendricks uses technology and fashion to push back against some of the ways that the white art world sees Black artists,” says Hill. “So often, the work of Black artists gets framed as political just because they choose to focus on their communities or themselves and their creative process.”

In another photograph made in 1967, Hendricks shows himself with a camera reflected in a shiny hubcap. It is a clever reinterpretation of Jan van Eyck’s “Arnolfini Portrait” of 1434 and Parmigianino’s “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror” made about a century later.

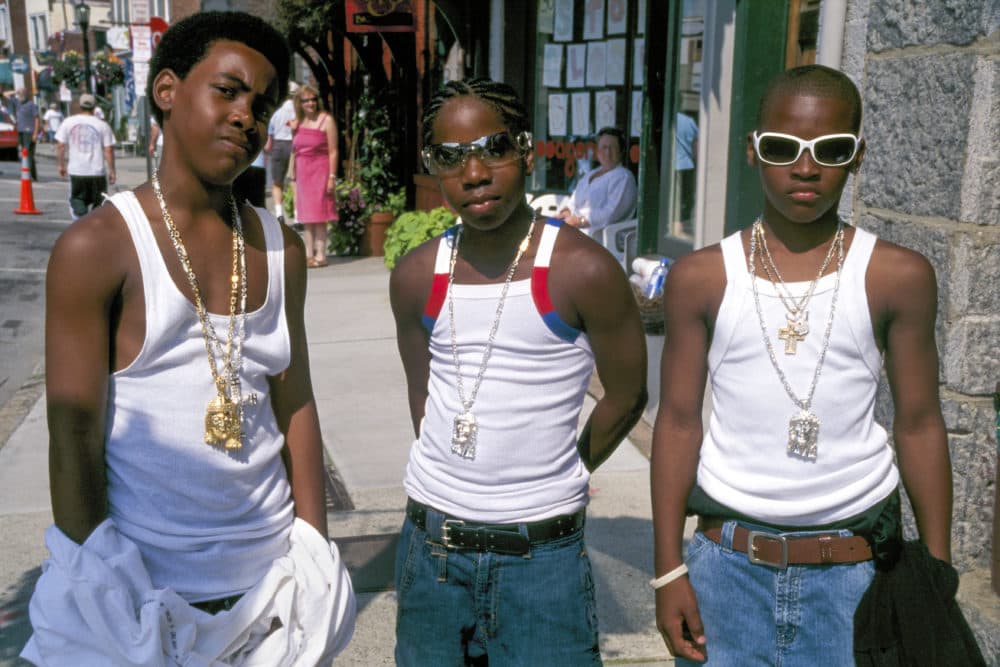

In a section dedicated to Hendricks’ photographs of others, we see images of two, three and four subjects taken in the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s. In one untitled photograph from 1995, we see three Black teenage boys in white muscle T-shirts wearing gold chains and a whole lot of attitude.

“They're boys who are absolutely performing an identity through dress and fashion,” says Ankori.

In a series of photographs around fashion, we see a Polaroid of women’s shoes that Hendricks collected because he felt that each pair embodied the essence of the woman who wore them. Almost hidden beneath the shoes is a sign we can barely make out. It reads “Slave Quarters,” thereby layering on more meaning about fashion, identity and the historical reality of being Black in America.

A passionate jazz lover, Hendricks also worked around the themes of the boombox and television, of which we see several abstract drawings that investigate the frame of the television screen. In one drawing, the television screen is transformed into a yin-yang symbol, which might speak to how technology has taken on a significance akin to a religion. In all, we see a portrait of an artist who was curious, playful and forthright, from his earliest painting days through all his experimentation over the decades and during his career as a professor of studio art at Connecticut College, right up through his death.

“The camera was a way of amplifying his capacity to see and to capture sights,” says Ankori. “He rejected the label that he was a political artist. He said, ‘I only paint my experiences.’ And I think painting his experiences as a Black man in America, growing up in the 1950s and ‘60s until 2017, if you show your world of course there are political implications.”

"'My Mechanical Sketchbook' — Barkley L. Hendricks & Photography" is on view at the Rose Art Museum Feb. 10-July 24.

Correction: An earlier version of this piece misdescribed the self-portrait the Rose Art Museum acquired in 2021. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on February 08, 2022.