Advertisement

At the ICA, a Boston artist illustrates the vibrancy of Black culture

In 1968, a group of Chicago-based Black artists formed a collective they called AfriCOBRA, short for the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists.

That’s not bad as in bad. That’s bad as in oh-so-good. Their idea, as stated in their manifesto, was to create an affirmative art representative of the African diaspora. It would “deal with the past,” “relate to the present” and “look into the future,” reflecting “the expressive awesomeness that one experiences in African art and life.”

Roxbury artist Napoleon Jones-Henderson was part of that movement. One of the original 10 founding members of AfriCOBRA, he was there on Sunday afternoons as the collective hashed out the core principles that define it even today.

“Most principally, they were to be positive images,” he says. “There was the use of words and the aspect of color. And the color was to be clearly bright and vivacious.” It was color, he says, to help “people move themselves to a better place.”

Jones-Henderson has dedicated his life to creating images that are “representative of the beauty of Black culture.” Now his electric Kool-Aid colored tapestries, animated mosaics and his haunting shrine-like sculptures are on view in “I Am as I Am—A Man,” the ICA’s long overdue survey of his work.

The exhibit is a rare opportunity to take in the full artistic breadth of an artist who has lived and worked in Boston since 1974, developing an appreciative following among those who have seen his ceramic tile mosaics around the city, including at the entry of the Roxbury Community College Library and at the Bruce C. Bolling Municipal Building in Nubian Square.

Jones-Henderson’s art, while adhering to AfriCOBRA precepts, stands apart.

“He is really unique in AfriCOBRA just for his translation of their esthetic principles into weaving,” says Jeffrey De Blois, curator of the show. De Blois met Jones-Henderson at the Boston Art Book Fair a few years back and was floored by the fact that an original AfriCOBRA member lived right here in town. “The exhibition aims to give a platform for understanding the cultural significance of his work in Boston and beyond.”

Advertisement

A native of Chicago, Jones-Henderson joined AfriCOBRA while still a student at the Art Institute of Chicago. He had been introduced to textile art in high school by a young, Black art teacher who wasn’t taken aback by her male student’s fascination with the loom. At the Art Institute, he continued training with German textile artist Else Regensteiner, who was influenced by Bauhaus design. Eventually, Jones-Henderson left Chicago to accept a year-long, part-time teaching position in the weaving department at MassArt.

“It was supposed to be a year and here we are now, 45 years later, I'm still here and enjoying the hell out of being here,” he says.

What kept him in Boston was the city’s proximity to textile mills that loomed lustrous silver and copper metallic yarns that would help his work to “shine,” another important tenet of AfriCOBRA.

“That shine is the thing that Black people are exuberant about,” says Jones-Henderson. “You definitely have to have your shine on when you went to church and other important events like parties and birthday celebrations.”

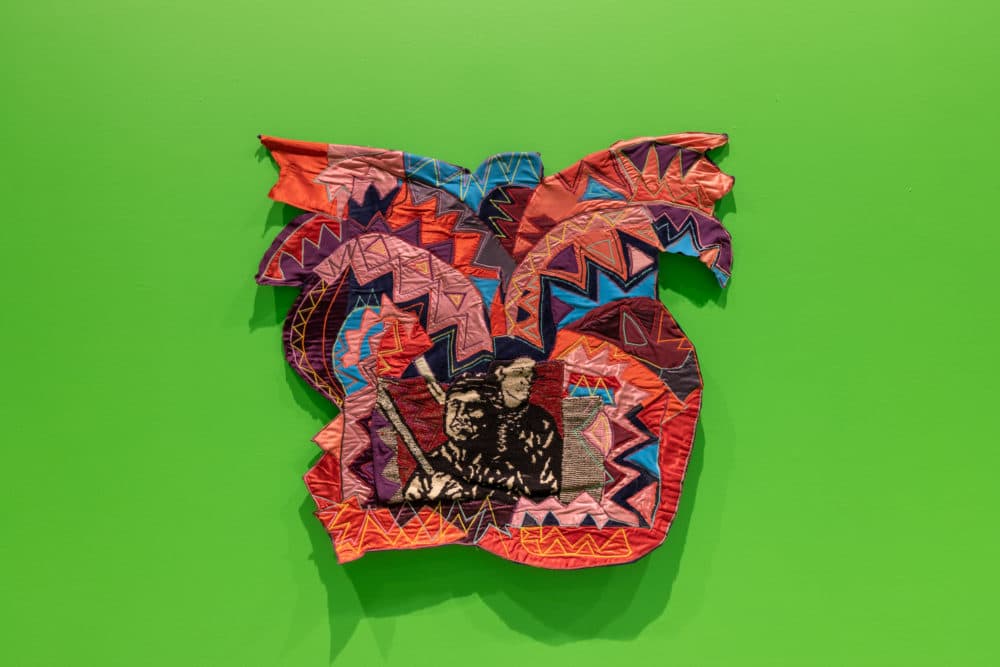

And shine his work does. Integrating African ritual sculpture, Southern vernacular architecture, and references to revered African American artists, Jones-Henderson has created works that are simultaneously celebratory and sober. While some pieces revel in the artistry of African American musicianship, like tapestries dedicated to Stevie Wonder and an applique and enamel piece dedicated to Duke Ellington, others function as a call to action.

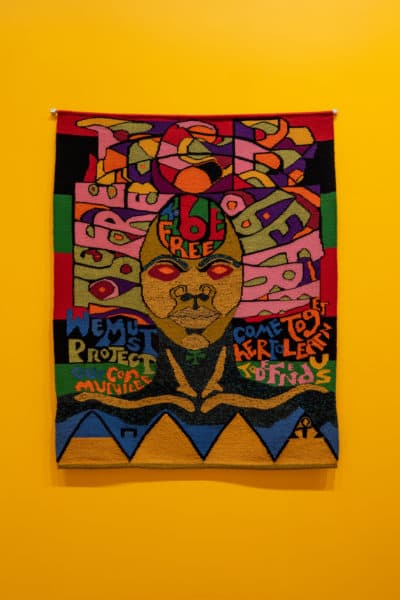

The large tapestry “TCB” is emblematic of Jones-Henderson’s oeuvre. Made in 1970 and based on a print made by AfriCOBRA member Barbara Jones-Hogu, the piece depicts the bust of a Black figure who could be male or female. In the figure’s resplendent afro, we see the words “be free” and “come together to learn to defend us.”

“It was a work that was pivotal in projecting the philosophical and esthetic principles of AfriCOBRA,” he says. “There’s frontality because the piece is looking directly out at you, engaging with you, inviting you, and having discussion and dialogue. The dialogue is exhibited through the words that are produced in the works.

“‘We must come together to defend our communities,’ that's part of what TCB is about—taking care of business, being supportive of your community, starting with your family and extending out to the larger community and then extending out to the larger African world.”

In another tapestry from 1975, we see the words “Stop Genocide.” The plea is woven of red and orange wool yarn set over an arresting patterned background of purple and blue. It is about the idea of stopping all genocide, against all peoples everywhere.

“It doesn't necessarily only speak to genocide in the physical context of killing people,” says Jones-Henderson. “But the genocide of killing people's spirit, killing people's minds, preventing people from being able to enjoy life.”

In the tapestry “A Few Words from the Prophet Stevie” made in 1976, and the tapestry “Mysterioso” made in 1987 in honor of Thelonious Monk, Jones-Henderson exults in musical genius using his gleaming yarn. But his celebratory work also extends to other mediums. “Blind Boys of Alabama” (2003-2007) is made of enamel on copper and shiny gold leaf on wood and is an homage to the legendary Grammy-winning gospel group.

A section of the exhibit is dedicated to elaborate “shrines” that Jones-Henderson builds in honor of those who have passed. In some cases, he regards these as a quiet place for restless souls who met a tragically violent end.

One such piece, “4 Little Girls-16th Street Baptist Church,” 2004-2010, is a small structure set atop a textile base sprinkled with cowrie shells that is dedicated to the children killed in the 1963 church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama. Only one of the four segregationists who committed the murder was ever prosecuted.

In “Requiem: Memories Past, Present and Future,” a windowless, doorless structure serves as a shrine dedicated to the those who died in the 1919 Chicago race riot. During that riot, one of many that swept the country in the years following the release of D. W. Griffith’s film “Birth of a Nation,” 38 people died, 537 were injured and between 1,000 and 2,000 people lost their homes.

“It's about honoring all those people who died in the 1919 riot and those who have died in the past, the present and those who undoubtedly will die in the future with regard to how we, as human beings treat and react toward each other,” says Jones-Henderson.

Looking back on the 50 years of artmaking as part of the AfriCOBRA collective, (still active today although group members meet over Zoom rather than in member Wadsworth Jerrell’s studio, as they once did), Jones-Henderson, a mentor to young artists near and far, looks back with pride and a little bit of awe.

“We took on some very ambitious projects for the purpose of making sure that there was art that meant something to Black people, available for them to have in their homes,” he says. “We said, ‘If you’re going to have art on the wall in the Black community, it’s going to be art that supports and is a positive image of yourselves and your history.’ And by that virtue, we have for 54 years, as a group of artists, made art with the same tenacity and commitment to the esthetics and the philosophy that we set up in 1968.”

Call it Black power.

“Napoleon Jones-Henderson: I Am as I Am—A Man” is on view at the ICA Feb. 17-July 24.