Advertisement

At the ICA Watershed, found objects are poetic and political

Upon entering “Revival: Materials and Monumental Forms,” now on view at the ICA Watershed, a visitor is confronted with two very large, very beautiful pieces of art.

One is a 48-foot-long installation by Jamaican-born artist Ebony G. Patterson who has created luxuriant paper collages filled with colorful blossoms, blades of grass and blue and purple flittering monarch butterflies. At first glance, it is simply a dazzlingly verdant garden that speaks to overgrown summertime backyard opulence.

In the same space, at the far end of the gallery, hangs a luminous shimmering work entitled “Area B” (2007) by renowned Ghanian sculptor El Anatsui. His glittering tapestry is as regal as a king’s mantle. The twinkling gold panels would seem to allude to affluence and prosperity.

But there’s more to both pieces than meets the eye. Upon closer inspection of Patterson’s five-panel garden installation, we see body parts — a face, a headless torso, a disembodied arm. Clearly, this is no Garden of Eden. And edging a bit closer to El Anatsui’s sculpture, we see that his golden tapestry is not made of expensive gold cloth, but of metal strips found around the necks of liquor bottles.

In short, while these pieces are certainly about beauty, they are also about much more, including plenty of hardship and anguish.

“I wanted this sense of a sparkling beginning,” says ICA curator Ruth Erickson, who organized the show with the help of curatorial assistant Anni Pullagura. “But then with both of those works we start to look at the underlayers.”

In fact, a multilayered exploration of labor and production, capitalism and consumerism, as well as the sustainability of it all, is the common thread running through the six installations that make up “Revival,” on view through Sept. 5. The theme was specifically chosen to reflect the site’s history as a copper pipe and sheet metal manufacturing plant for ships.

Patterson’s garden is not just a lush garden but also a reflection on the economic engine of colonialism and its effect on the African diaspora. There is sweat and blood here, but somehow, inexplicably, also beauty.

Likewise, El Anatsui, who lives and works in Nigeria, also references colonialism and exploitation.

“In much of his work, he’s thinking about the use of gold and alcohol and sugar,” says Erickson. “He’s also thinking about the triangle trade and about the ways in which goods and people have moved from the global south to the north, and the deep inequalities built into our world.”

In a show about labor, production, economic systems and connections, Madeline Hollander’s piece, “Heads/Tails: Walker & Broadway 2” (2020), reflects on how interconnected our lives truly are. Standing 46 feet long and 14 feet high, it is a wall of flashing car headlights and taillights salvaged from auto collision centers. The lights were originally programmed to flash in sync with the traffic lights of a New York City intersection. The artist, who lives between LA and NYC, is a trained classical ballerina and choreographer and often incorporates movement into her work. For this piece, she wanted to explore the choreography of traffic, which is also intimately connected to the movement and distribution of goods.

Advertisement

Ibrahim Mahama is an artist best known for draping buildings in jute sacks. His work grapples with migration, commodities, human labor and globalization. Mahama once said that he enjoys working at a very large scale because “when you see something every day on a human scale, you become numb to it. But when you see it on a very large scale, suddenly it draws you in.”

For “Revival,” Mahama created two massive towers of stacked crates incorporating shoes and other objects in response to the shoeshine boys that wander the streets each morning in his native Ghana. His piece “Non Orientable Paradise Lost 1667” (2017) is constructed of the boxes shoeshine boys use as makeshift drums to get clients’ attention as well as a staging area for the buffing of clients’ shoes.

“He was really interested in how this one object tells the history of where those laborers got their materials,” says Erickson. “Oftentimes, they're repurposing crates or they're repurposing objects that they may have collected to create these boxes. And then he is repurposing them again by collecting them and including them in these large-scale sculptures and installations.”

Karyn Olivier, an artist born in Trinidad and Tobago, has created her own enormous 23-feet tall installation entitled “Fortified” (2018-2020). It uses bricks set one upon the other (held together fortunately by a steel armature) but in place of the usual mortar we find baby clothes, women’s skirts and men’s shirts. The brick wall seems to be an impenetrable fortress.

“But coursing through its very structure is this clothing,” says Erickson. “And so, it feels like a kind of persistence of humanity, despite the structures that we build to try and keep people and humanity at bay.”

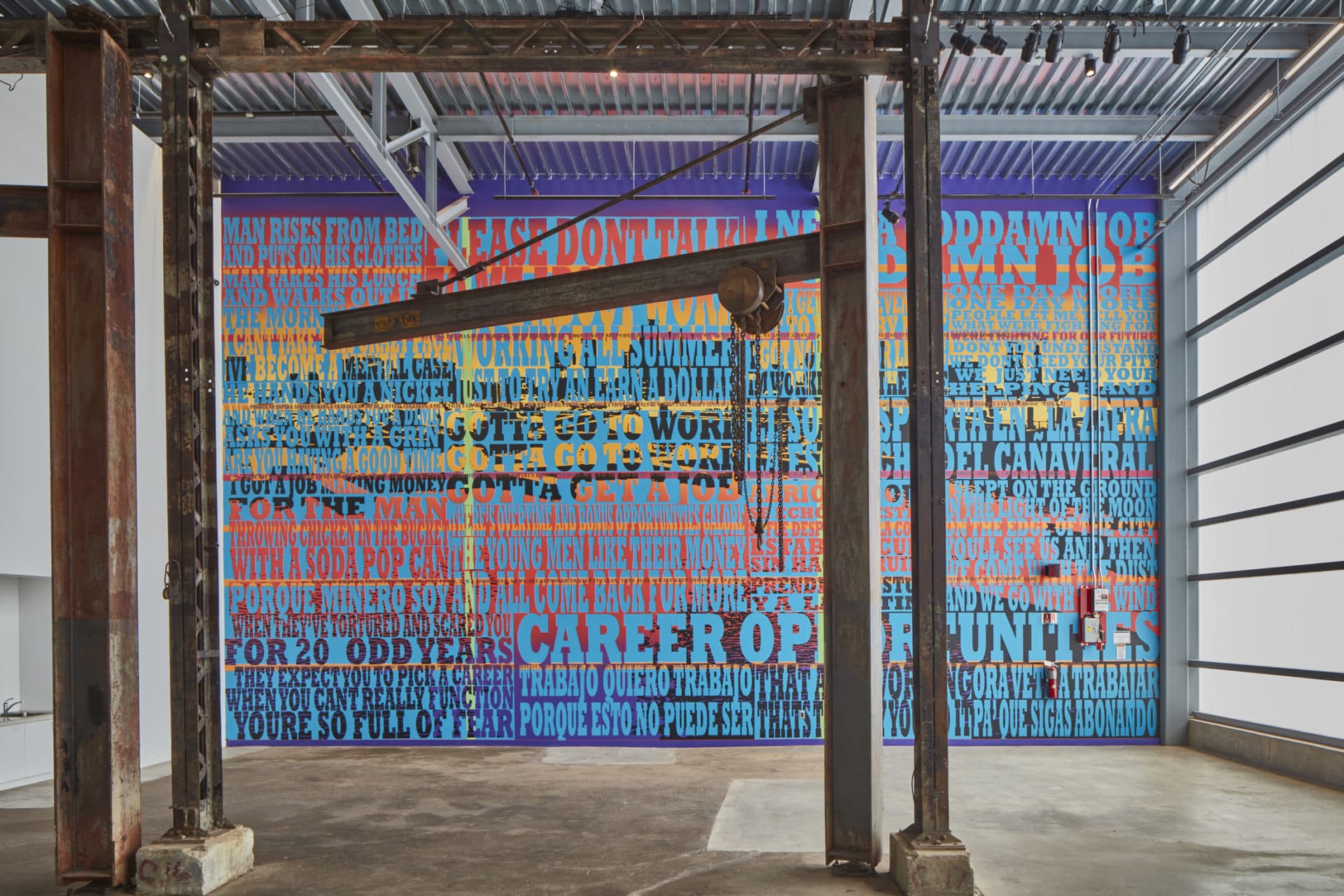

Also included in the exhibit is a piece by Jamaica Plain artist Joe Wardwell. Wardwell, an associate professor of fine arts at Brandeis, who may be best known for his mural at the Roxbury branch of the Boston Public Library, specializes in huge colorful works incorporating words. For “Revival,” he has created another colorful, complex mural around the idea of labor.

Painted in bright blues and purples, the mural incorporates song lyrics about work from musicians ranging from Woody Guthrie to The Clash. His mural includes landscape views glimpsed from East Boston and plays off the interior vertical and horizontal architectural lines of the Watershed building itself. In addition to song lyrics, Wardwell includes quotes from actual workers interviewed for Brandeis University’s Cascading Lives Project. The workers reflect on how their lives have been upended by the arrival of COVID-19.

“It's a testament to the radical ways that work has transformed for many people in just the recent past with COVID,” says Erickson. “I like the piece because it goes from the site to a kind of shared popular culture, and then it pulls back in a way to the people who inhabit this neighborhood. For me, it connects all those dots, which was very much the impetus of the exhibition, to connect the site with its role in global trade, migration, human history.”

“Revival” is a show that is impressive not only for its massive scale — very big things always make an impression — but for its focus on artists who make reuse and reclamation of materials a fundamental part of their practice. Once again, we are offered an opportunity to reflect not just on how hard we work, but how much we consume and, in the end, how much we throw away.

“Revival: Materials and Monumental Forms” is on view at the ICA Watershed through Sept. 5.