Advertisement

Ru Freeman probes her characters' private lives in 'Sleeping Alone'

Partway through the title story of Ru Freeman’s “Sleeping Alone,” the main character Sameera thinks: “You won’t understand; you who are not me.” And still, she continues to reflect on the destructive political act she is planning, as if detailing her actions will explain and validate them.

Though each story in this collection is an independent narrative, the inability to truly see others, and the consequences that ensue are a recurring theme. Sameera may be convinced that others will not understand her, but she also considers entire groups of people “dispensable.”

The settings in “Sleeping Alone” range from small towns to large cities, but geography is less a determining factor than politics or class; there is a tale of complicated, unrequited love between an Irish woman and Sri Lankan man (“The Irish Girl”), and a young basketball player burdened by family responsibilities, trying to navigate his high school’s racial and economic cliques (“Kobe Loves Me”). Freeman is not afraid to linger in disquiet. The eleven individual stories tell of many kinds of heartache, more than it would seem a slim volume could hold.

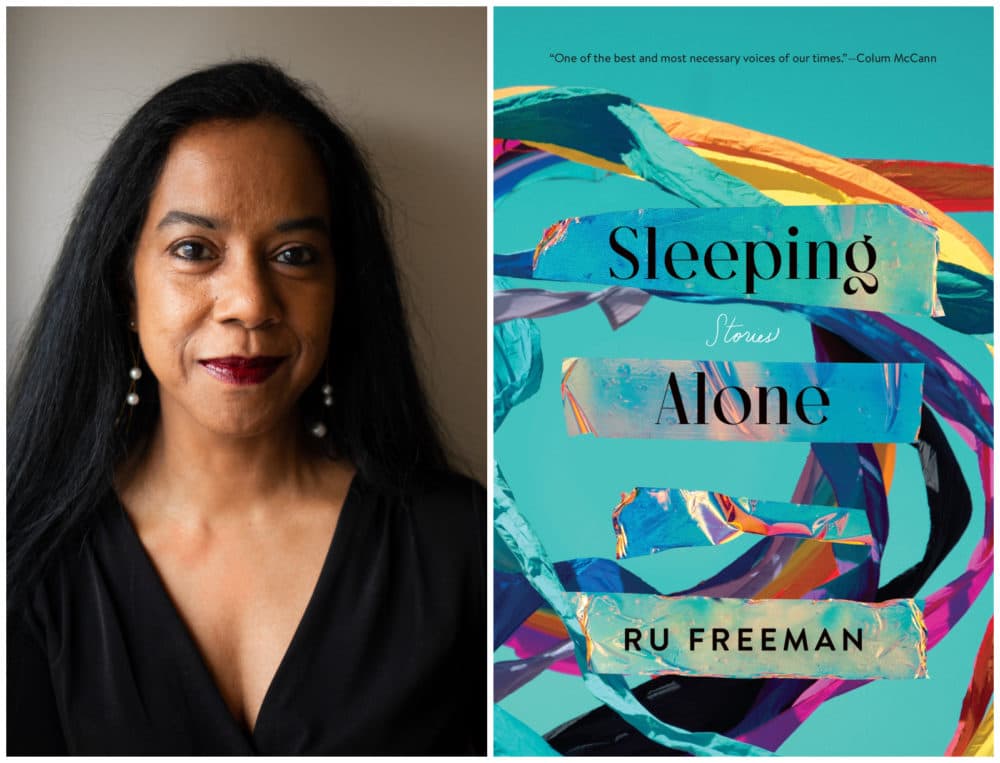

Born in Sri Lanka, Freeman is the author of two previous novels, “On Sal Mal Lane” (2013) and “A Disobedient Girl” (2009), that have been translated into multiple languages. Her essays and book reviews have been published in The New York Times, the Guardian, and the Boston Globe.

In a 2015 essay for the Guardian Books Network, Freeman described her upbringing in Sri Lanka, her early love of reading, and learning how to read and write in English: “there was an internal rhythm to our understanding of the English language that did not seek to obey a single aesthetic.” Freeman’s ear for language is evident; each story in “Sleeping Alone” has a distinguishing voice and a writing style tailored to its content.

In “The Bridge,” a teacher who is also a veteran protests a war every Sunday afternoon on a bridge in Maine, which he considers “my church. My weekly reckoning with God.” An ordinary man who’s been forever changed by horrific events, he feels distant from his fellow teachers, who seem comfortably secure in their familiar lives. Sentences in “The Bridge” feel purposefully compressed, their content uncoiling far beyond the number of words, especially as more wartime circumstances are revealed.

In “Matthew’s Story,” twenty-something Matthew wanders through a crowd of relatives and friends gathered to mourn his younger brother Gabriel, killed in an accident. The brothers had always been close; Gabriel was the cautious one, happy to experience adventures secondhand through Matthew’s escapades. That is, until the night before his wedding. Matthew’s outward conversations with guests are flooded with his internal images of Gabriel; his regrets are interwoven with fearful questions about the future. All float within a finely-written present-tense fog of grief.

Advertisement

“Fault Lines,” one of the strongest stories of “Sleeping Alone,” is told through the rotating perspectives of women whose lives intersect through jobs and some of their children's schools. Using smoothly arch phrases, Freeman creates a community of disparate worlds of privilege and struggle that overlap, but can never actually connect.

Gabriella is nanny for the children of Mira, a successful Black businesswoman (who is sometimes mistaken for a nanny when she drops off her kids at school). Gabriella has her own family, including a 15-year-old son who has been accepted to a prestigious high school across town. It makes Gabriella “happy-sad-angry” to hear about his amazing teachers, his free MacBook Pro, his tutors — enrichments that will always be lacking for her other children at their neighborhood school. Each weekday, Gabriella's friend Iris leaves her house at dawn to care for her client's children, who are "expectant of an excess of attention in all aspects of their lives from baths to play to reading to naps." Each weekday, Iris relies on her oldest son to wake his younger brothers, make everyone breakfast, and get them all to the neighborhood school on time.

Everyone’s lives are tightly scheduled, but unexpected changes affect some women much more than others. For the women in “Fault Lines” with little buffer between themselves and chaos, Freeman shows how even a minor scheduling glitch can have disastrous personal costs. This is an unnerving portrait of people who, no matter how determined or hardworking, are little match against larger cultural or economic forces.

Too often, those most vulnerable to chaos (financial, personal, marital) are unseen. In this and other stories of “Sleeping Alone,” Freeman makes visible lives that are often hidden in plain sight.