Advertisement

Harvard Film Archive screens retrospective 'The Complete Federico Fellini'

As part of our local repertory theaters’ conspiracy to keep me from spending any time outdoors this summer, over the next three months the Harvard Film Archive will be screening “The Complete Federico Fellini,” a comprehensive retrospective of the Italian cinema legend’s entire filmography, which contains more masterpieces than I can count on one hand. The great director’s centenary passed during the early days of the pandemic, so instead of a series like this one, fans were stuck celebrating with the Criterion Collection’s handsome, if incomplete, “Essential Fellini” box set, the exclusions from which prompted more than a few arguments online about the definition of the word “essential.” Happily, you’ll find no such elisions in the HFA program, which runs from Friday, June 10 through Monday, Aug. 15 and includes 21 feature films, as well as assorted shorts and television projects, allowing a view in full of a gloriously grandiose filmmaker who, for better and worse, was never less than entirely, indomitably himself.

You can spot a Fellini film from a single frame. Even his initial, unpolished efforts have a heightened quality that feels a little larger than life. A sketch artist from a quaint seaside village on the Adriatic coast, Fellini never lost his childlike wonder at the wide world around him — even if that child was more like a naughty pubescent boy, often driven to distraction by big buttocks and breasts. He kept a cartoonist’s sensibility in his appreciation for exaggerated lines and curves, and as the later films grew more explicitly artificial, they came to look more and more like his drawings come to life. He was fond of blaring music while shooting scenes, which is why characters always appear to be slightly swaying to the wistful waltzes or lonely trumpets of Nino Rota’s scores. His contemporaries in the neorealist movement made it their mission to show the world postwar Italy as it was. Fellini was more interested in the Italy of his imagination.

The series kicks off this weekend with the quartet of early classics that cemented Fellini’s reputation. We begin, as any retrospective must, with 1953’s “I Vitelloni.” His loosely autobiographical third feature chronicles the wasted days and nights of four loutish young men going nowhere in the kind of small, provincial town from which its director had fled. At once affectionate and clear-eyed about these characters and their shortcomings, this extraordinarily influential picture launched an entire genre of what I guess you could call “guys being dudes” movies, serving as the template for “Mean Streets,” “Saturday Night Fever,” “Diner,” “Trainspotting” and so on. (You can spot one of the most famous tracking shots from “Goodfellas” early in the film. Heck, you can see most of Martin Scorsese’s career in it.)

His 1954 “La Strada” and 1957’s “Nights of Cabiria” both feature Fellini’s wife and muse Giulietta Masina getting battered about by the fates and finding grace in misfortune. In the first, she stars as a simple peasant girl, sold to a brutish circus performer played by Anthony Quinn in a heartbreaking fable of unconditional love and the men who hate themselves too much to receive it. The latter is a more taboo affair, foreshadowing Fellini’s scandalous films to come, starring Masina as a streetwalker who gives of her heart too freely and pays dearly for her misplaced faith in others. (Bob Fosse refashioned the story into the Broadway smash “Sweet Charity.”) Yet Cabiria always bounces back, an irrepressible spirit in a carnivalesque closing sequence that solidified the director’s signature style.

1960’s “La Dolce Vita” was the pivot point when Fellini stopped shooting in the streets and instead recreated the Via Veneto on the soundstages of Cinecittà Studios. It’s a tale of ascensions and descents, juxtaposing the sacred and the profane as seven wild nights become weary mornings in the life of Marcello Mastroianni’s wastrel writer, frittering away his literary ambitions in heedless pursuit of wine, women and the so-called sweet life. In Mastroianni, Fellini found his ideal avatar, a debonair, devastatingly handsome figure with the soul of a clown. In their collaborations that followed, the actor brought a boyish sense of play to the director’s surrogate, oversexed scamps. He leavens the self-pity with a wry smile.

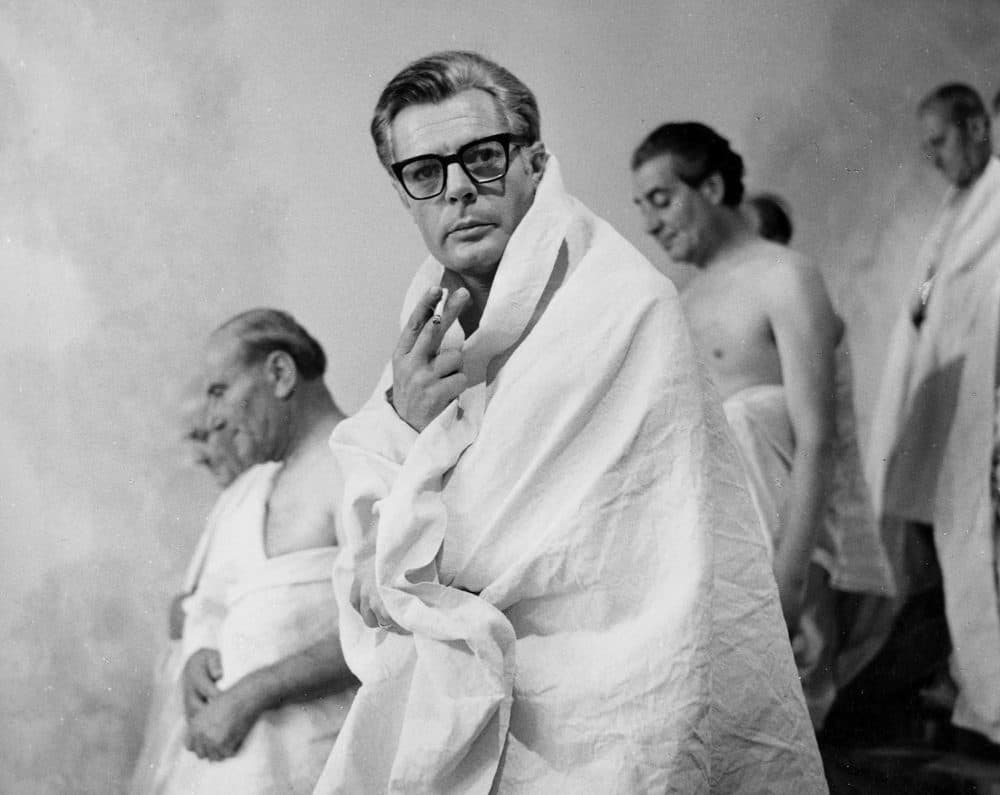

Never more so than in the 1963 “8 1/2,” Fellini’s gloriously self-indulgent saga of an acclaimed international filmmaker who has run out of ideas. Stalling and putting off his financers, mistresses and producers, Mastroianni’s Guido takes refuge in his overwrought, erotic reveries while sets are being built for his still-unwritten film. (The towering, phony rocket ship being erected in the distance provides a hilarious visual analogue for the character’s impotence.) Fellini gets a bum rap by some for how his camera likes to leer at the generous attributes of his actresses, yet few filmmakers have been so perceptive at exposing the fundamental ridiculousness of the male psyche, as when Guido fantasizes about a harem of beautiful young women bathing him like an oversized baby.

The autocritique continued in 1980’s flawed, fascinating “City of Women,” stranding Mastroianni’s aging, anachronistic rake in a brave new world of women’s rights and female empowerment movements. The movie is interrogating itself from its opening moments, an offscreen voice heckling the credits, “Marcello again?” Poorly reviewed and apparently “inessential” according to the Criterion box, it’s an occasionally tiresome movie that’s all about how tiresome this character has become, his sexual hangups hung out to dry.

Advertisement

The HFA series gets weirder as the summer wears on, following Fellini’s films deeper into artifice after “8 1/2.” Extravagantly designed and increasingly removed from any recognizable reality, these later pictures are products purely of their director’s subconscious, which was never all that far from the surface to begin with. Fellini’s name wasn’t just above the title, it was actually included in the original U.S. titles of films like 1969’s “Satyricon” and his 1976 “Casanova,” ornate, semi-impenetrable affairs that turned decadence into a sort of aversion therapy. The latter was one of the wildest films I watched for the first time during lockdown, starring Donald Sutherland as the legendary lothario, joylessly humping his way through 18th-century Venice with such mechanical indifference it’s fitting that he finally only finds happiness with a robot. (When asked about his unlikely leading man, Fellini famously confessed that he’d cast Donald Sutherland because he “wanted a Casanova with the eyes of a masturbator.”)

Rarely screened B-sides that the HFA has programmed together, “The Temptation of Doctor Antonio” and “Toby Dammit” are two terrific shorts Fellini contributed to omnibus films in the 1960s. The first, culled from 1962’s “Boccaccio ‘70,” in which Italian directors were invited to riff on stories from “The Decameron,” features Fellini’s first foray into color photography. It’s the screamingly funny story of a puritanical physician driven mad by a sexy billboard of Anita Ekberg (in all her voluptuous splendor, amusingly advertising milk) and is obviously the filmmaker tweaking Catholic censors who had just lost their minds over “La Dolce Vita.” The freaky, phantasmagoric “Toby Dammit” comes from 1968’s “Spirits of the Dead,” and reworks Edgar Allan Poe’s “Never Bet the Devil Your Head” into the tale of a drug-addled movie star (Terence Stamp) stalked by a demon child after arriving in Rome to shoot “a Catholic western.” It’s a terrifying, tantalizing peek at what might have been had the director instead pursued a career in genre pictures.

Fellini’s swan song, 1990’s abysmally received “The Voice of the Moon,” starred Roberto Benigni and never got a proper American release. (I’m excited to finally see it, despite everything I’ve heard.) The HFA has wisely shuffled the chronology to instead close out their program with his beloved 1973 “Amarcord.” A return to his seaside village of Rimini some 20 years after “I Vitelloni,” this rapturously beautiful, rambunctious reminiscence revisits Fellini’s boyhood as a series of tenderly sentimental, at times side-splittingly earthy anecdotes and tall tales. (I showed the movie to my 13-year-old nephew last summer, correctly guessing that the barrage of boobs and fart jokes would overcome his aversion to subtitles. “Amarcord” is a great gateway drug to get kids into foreign films.) It’s a fitting finale to the HFA series, showcasing the director still at the height of his powers, turning memories into myth.

“The Complete Federico Fellini” runs at the Harvard Film Archive from Friday, June 10 through Monday, Aug. 15.