Advertisement

Review

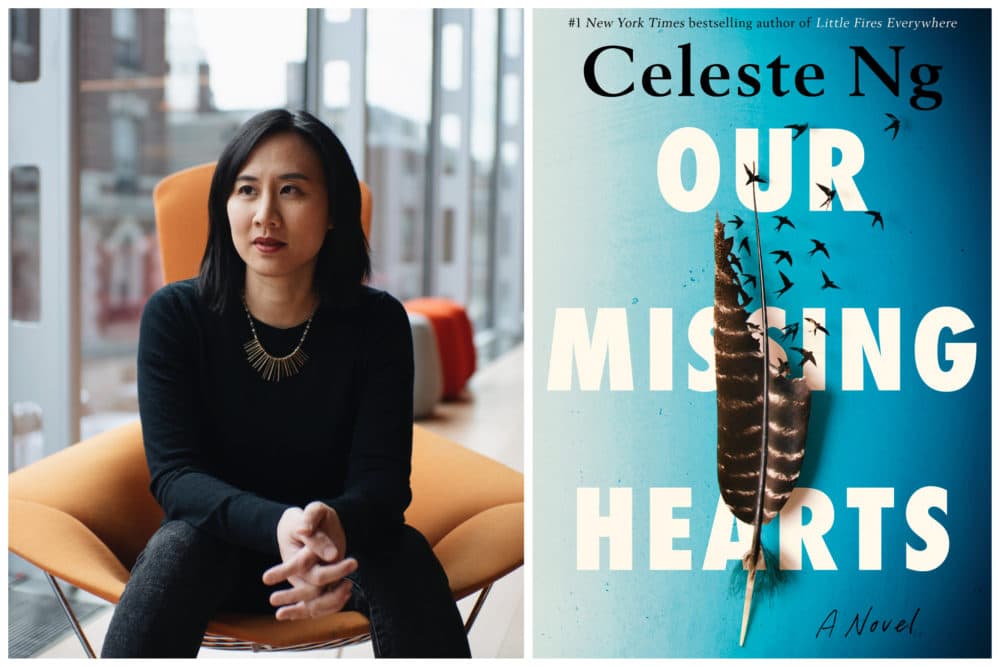

Celeste Ng's 'Our Missing Hearts' chronicles a dystopia that hits close to reality

More than ever, the challenge today in writing dystopian fiction is that in the lag between when the manuscript is submitted and the book is published, chances are disturbingly good that the reality will have surpassed anything the author imagined. Celeste Ng, the Cambridge-based author of “Everything I Never Told You” and “Little Fires Everywhere,” acknowledges as much in the letter to her readers at the start of her newest novel, “Our Missing Hearts” (out Oct. 4).

“In mid-2016, after I finished drafting ‘Little Fires Everywhere,’ I started what I thought was a fairly traditional novel about a mother and her adolescent son. But as I wrote, the world began to shake along long-ignored fault lines, and the last few years have felt particularly cataclysmic. The story shifted as I wrestled with questions raised by the reckonings taking place—or being avoided.”

As any student of recent history will recall, those included the U.S. government’s removing children from the custody of their immigrant, asylum-seeking parents at the southern border, and the dramatic rise in violence against Asian Americans in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Layering on to those “reckonings” are the recent measures to ban books from school libraries and curricula that deal with sexual identity and racism. All of these ongoing policies and whipped-up culture wars loom large in the plot of “Our Missing Hearts."

Bird Gardner is a 12-year-old boy living in a tiny Cambridge dorm room with his father, a former linguistics professor who now shelves books at Widener Library. His mother, a Chinese American poet named Margaret Miu, left her husband and son when Bird was 9 and has had no contact with either of them since. Bird’s age, coupled with his father Ethan’s extreme protectiveness, has limited his understanding of what has transpired.

As adult readers, we recognize what Bird can’t. In the aftermath of a dark period referred to as The Crisis, American equilibrium is enforced by a sweeping law intent on preserving “American Culture.” Considered to be a leader of the resistance to the new censorship and cultural nationalism, Margaret is a fugitive. But when Bird receives an unsigned letter containing nothing but drawings of cats, he realizes that Margaret is trying to contact him and sets off to find her.

When showing us the world through Bird’s eyes, Ng’s language is subdued, reflecting the boy’s flattened affect and limited understanding. The constraints and monotony of his present — going to school and coming straight home, keeping his head down — are relieved only when Bird allows himself to revisit his former home and long-suppressed feelings, when “memories hover close before alighting on his shoulder like dragonflies.”

Now and then, when Ethan revives enough to tell Bird about the origins of words, we get a sense of how rich this hollowed-out family’s life once was.

Indeed, the quest to find and flex the power of language is the central conceit of this book. And when we finally meet Bird’s poet mother, Ng’s prose quickens, becoming more complex, the ideas more nuanced, the relationships spikier. Read Margaret's reflections on her parents, immigrants from Hong Kong, who believed that “blending in … was their best option.” They studied the clothes and toys of neighborhood children and carefully emulated them. “Suburban camouflage from the Sears catalog,” Margaret recalls.

“Her father’s saying: The stick hits the bird that holds its head the highest. Her mother’s: The nail that sticks up gets hammered down. She never, in her memory, heard her parents say a word in Cantonese. Only later would she realize what she’d missed.”

Margaret has since learned — as have so many of us who have relied on tasty meals and streaming videos to inure ourselves to the effects of increasingly dangerous culture wars — that staying silent or anesthetizing oneself with creature comforts doesn’t ensure safety.

As Ng’s readers will recognize, a steady parade of outrages — children separated from their parents at the border, climate and political refugees drowning or broiling to death in locked trucks, the unapologetic embrace of Christian nationalism and the assault on people’s bodily autonomy — are just as likely to make us shut down as to act up. So, when the government began removing children from “subversive” or undesirable homes, “The simple truth was that like most people, Margaret did not think much about any of this. The new act focused on those who held un-American views — but she was doing nothing of the sort. She was buying a table runner, warm slippers, a new bedspread.”

Since then, Margaret has spent her years in hiding collecting and recording stories from other parents who have been separated from their children. As she does so, she wonders: “And how much of a difference can it make really, just one story, even all these stories taken together and funneled into the ear of the busy world … how much of a difference could it really make, what change could it possibly bring, just these words, just this thing that happened once to one person that the listener does not and will never know?”

The answer to this anguished question becomes evident as we read the tales she has collected, stories that are hidden all around us in the world off the page.

“What would you want to say to your child,” she asks the bereft parents she meets.

In the responses to that simple inquiry, the book finally bursts out of its hush. In chronicling the specificity of parental love, “Our Missing Hearts” pierces and reanimates our weary ones.