Advertisement

Review

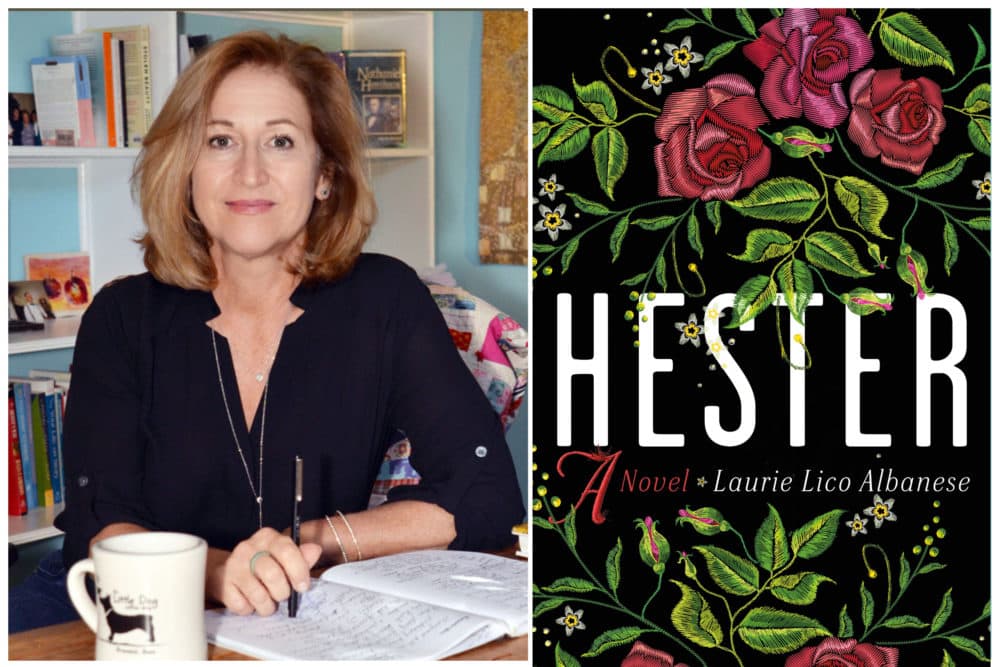

New novel imagines Hester Prynne's origin story

Historical fiction featuring real-life characters is having a bit of a moment. In the last two years, bestseller lists have included novels showcasing notable real people as main characters, including William Shakespeare in Maggie O’Farrell’s “Hamnet” and Thomas Mann in Colm Toibin’s “The Magician.” Of course, with the Wolf Hall trilogy on Thomas Cromwell and the Tudors, the late Hilary Mantel had elevated this form.

All historical fiction contains a degree of speculation, but some novels in the genre grow directly from the question “What if?” This is what drives Laurie Lico Albanese’s engrossing “Hester,” in which a 24-year-old Nathaniel Hawthorne falls into a forbidden romance with Isobel Gamble, a (fictional) 19-year-old seamstress whose talent with needle and thread seems almost magical. Set in Salem years before Hawthorne became famous, “Hester” posits an intriguing theory about the origins of “The Scarlet Letter.”

For good or ill, unexplained details in a celebrity’s life can serve as a siren song to novelists. (In fact, “Hester” is not the first novel to speculate on an aspect of Hawthorne’s personal life. He was the subject, with Herman Melville, of Mark Beauregard’s 2016 novel “The Whale: A Love Story.”)

In her author notes, Albanese writes that in his twenties Hawthorne transformed from a college rabble-rouser to a subdued, solitary figure. Part of this may have been simply maturity. But Albanese does highlight “a guilt and shame that Hawthorne carried all his life” (as some literary scholars have also done). Was it due to his ancestors’ roles as judges in the Salem witch trials, or his own actions?

It’s significant, however, that this book is titled “Hester,” not “Dimmesdale.” Hawthorne plays a pivotal role, but this is Isobel’s story, told entirely from her point of view – a view that reflects some surprising courage and independence. Hawthorne is portrayed as a charismatic but brassbound young man, unwilling to step outside the comfortable confines of his social class.

Nineteen-year-old Isobel and her husband Edward arrive in Salem in 1829 eager for a fresh start. Back home in Scotland, Edward, an apothecary shop owner, had driven them to the poor house with a ruinous opium addiction. They barely get settled when Edward leaves for a months-long ocean journey, hoping to gather exotic plants for his business. He has no remorse about leaving Isobel alone in this new country, or about the savings he steals from her to fund his passage.

Left on her own and nearly penniless, Isobel finds work at a local shop tailoring clothes and embroidering gloves and other accessories. (Descriptions of sumptuous fabrics and Isobel’s intricate embroidery designs are one of the book’s great pleasures to read.) Though the shopkeeper recognizes her extraordinary artistic talent, she pays Isobel an unconscionably low fee, in part because, with her red hair and her deep Scottish accent, Isobel is an outsider.

As with her previous historical novels (“Stolen Beauty” and “The Miracles of Prato”), Albanese enlivens “Hester” with many era-specific details, including early 19th-century fashions, medicines, even birth control. She depicts Salem as a sophisticated world trading capital and a town whose history is older than the country. It boasts a busy wharf area, grand houses, an abundance of shops and institutions (including real-life establishments like Hamilton Hall, the Salem Gazette, and the East India Marine Society Hall) — and an airtight social hierarchy.

Isobel forms her own supportive community of shopgirls and housemaids from diverse backgrounds; she muses that “there is a long requisite of what a person must do, say, and be, in order to be truly American.” Albanese slyly shows how these often-invisible women know more about the inner workings of the town than some of the well-connected families.

Isobel keeps running into Nat Hathorne (the surname’s original spelling, before he later changed it to Hawthorne). Their encounters evolve from banter to flirtations to passionate romance. They’re both aware of how dangerous their relationship is; a woman can be banished from Salem for adultery.

Even infused with books and merchandise and food from around the globe, the Salem of “Hester” — just a few generations from the witch trials — has a wide vein of judgment and suspicion running through it.

Much of “Hester” is about secrets, and Albanese persuasively illustrates how a secret can empower or corrode the spirit of the person carrying it. As a dressmaker, Isobel knows something about necessary deceptions, how to mask flaws and draw the eye where you want it to go.

Moreover, from a young age, Isobel has been skilled in a different form of deception. Though she wouldn’t have a name for it, she has a form of synesthesia — her mind links letters on a page and words that people speak to particular colors and hues. She knows her difference might be viewed more as witchcraft than biology; she comes from a long line of women who had, as her mother called it, “the colors,” and some had been cruelly punished for it.

Isobel does share her secret with Nathaniel, telling him she sees A as red, B as blue, C as yellow, but that A is not just red, “A is a scarlet letter. …Red is passion and knowledge, but it’s also a warning of pain.”

In the book’s only structural distraction, Albanese alternates the main story with vignettes of Nat’s and Isobel’s ancestors. Less would have been more, so as not to slow the momentum of an otherwise compelling tale. Nat has a cynical view of Salem’s upstanding elite, including his family, as harboring shadowy histories that encompass descendants on both sides of the infamous witch trials. He tells Isobel “I know man’s nature better than most because I see what others refuse to. … that’s what I’m trying to put in my stories.”

Although, in “Hester,” Nat can be morally obtuse as well. When Isobel, horrified, relates a poster she’s seen about slavecatchers in town searching for runaways from a Baltimore plantation, Nat shrugs it off, saying “It’s best not to interfere in the property of others.”

Her rare gift, which she has learned to nurture and conceal, has given Isobel the insight to see people as they really are, much more so than Nat. She begins to wonder if the very impossibility of their affair — her marriage, the enormous gap in their social standings — might be part of Nat’s attraction to her. She begins to understand she will need to create her own, new life. And she knows, deep in her heart, that the emotional cost will be much dearer for him than for her.