Advertisement

Review

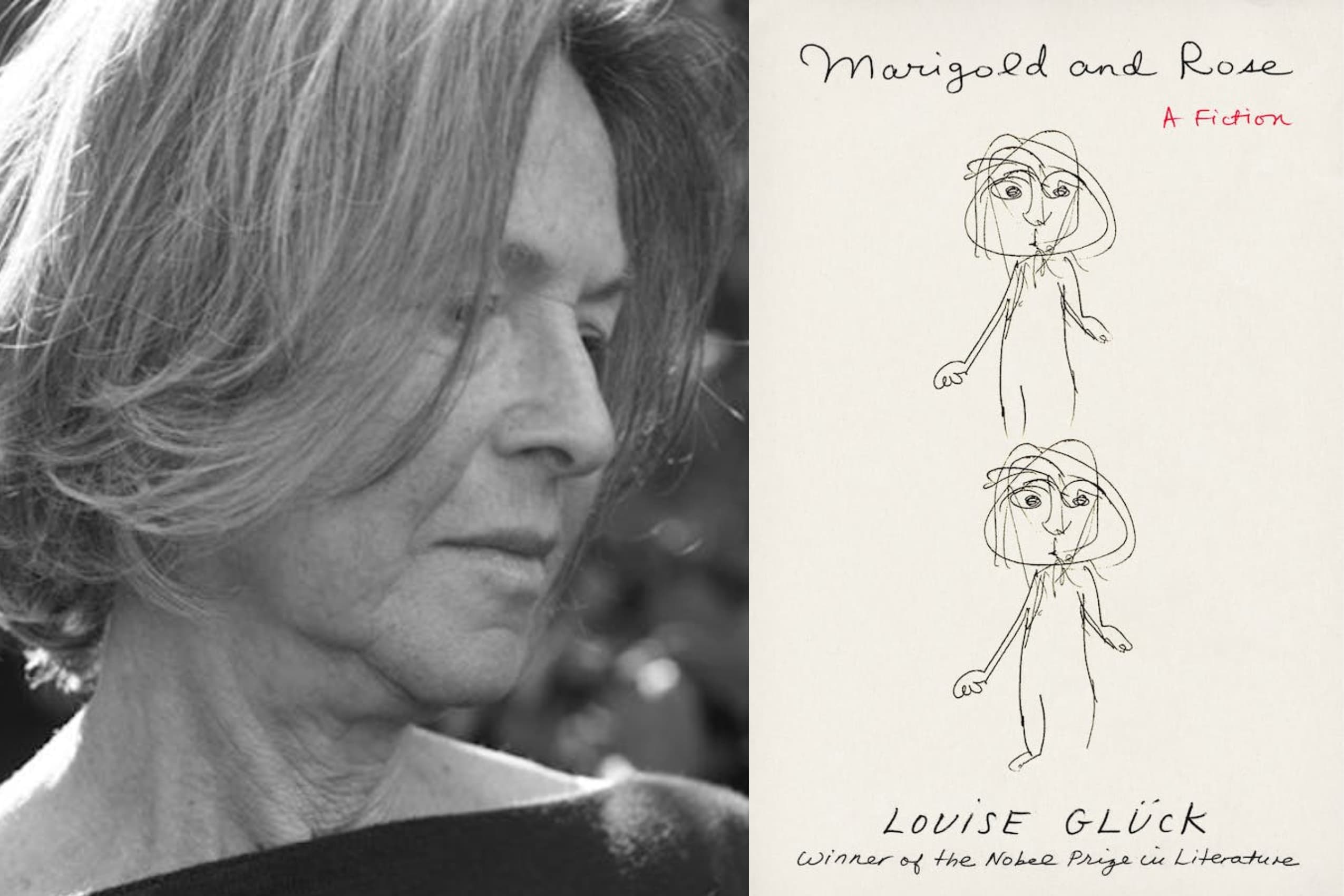

Louise Glück's latest book explores the miraculous world of infants

When my daughter was an infant, the smallest, most inconsequential things took on outsized meaning. For a year or so, I was reminded of what it was like for your whole universe to be little more than what you could see with your eyes and grasp with your hands. To be entirely focused on the people closest to you, to be free from the weight of the past and the uncertainty of the future. To live in the present and appreciate the novelty and, frankly, miraculous nature of things that adults take for granted, from colors to feelings to how to form the muscles of your face into a smile. And, through the process of attempting to explain the world to her, to recognize the arbitrary nature of things we deal with every day—analog clocks and irregular verbs, for starters.

More than once, I wondered if the intuitive solutions and methods she’d devised were more elegant than the “correct” ways I was trying to instill in her. I wanted nothing more than to understand what it was like to see the world the way she did, completely fresh and for the first time. I wanted to know what was going on inside her head. And I still remember the day, shortly after she started speaking, when she tried to tell me exactly that. She put her head in her hands and through gritted teeth groaned, “I don’t have the right words!”

Nobel Prize-winning poet Louise Glück does, however. In her latest work, a bit of prose gossamer titled “Marigold and Rose” (out Oct. 11), she puts herself into the minds of the titular twins as they experience their first year of life, examining their budding personalities, their inner lives, and the, well, poetic way in which they make sense of the world around them. Inspired by videos of her twin grandchildren in California during the pandemic, the Cambridge-based Glück quickly dashed off this fictional narrative—her first after a dozen well-regarded collections of poems.

What began as sketches trying to make sense of the behavior and interactions she witnessed on the videos evolved into something cute and quirky, to be shared with friends and family, and, ultimately, became a more polished work intended for public consumption. Given this provenance, the book is, of course, a bit of a flex on Glück’s part—a grandmother’s brag book with the weight of the publishing industry behind it. It could have easily come off as self-indulgent. But Glück’s knack for finding beauty in simplicity, and her ability to conjure up that sense of mystery and wonder that I remember feeling when my daughter was that age, make “Marigold and Rose” a pleasant read.

Neither Marigold nor Rose can speak, but from the very first sentence, Glück imagines them as fully formed people, with personalities, opinions, and desires that simply have no means of manifesting themselves. “Everyone understood that Marigold lived in her head,” writes Glück, “and Rose lived in the world.” Marigold, a self-doubting introvert, is keen to absorb as much as she can about the world for the book she one day plans to write. She can’t help but compare herself to Rose, who, at the tender age of just a few months, already exudes an effortless grace that makes Marigold feel inadequate. But Rose herself envies Marigold’s tenacity and resourcefulness, and imagines that only as a pair are they truly complete.

Very little happens in “Marigold and Rose,” at least from an adult perspective. A house replaces an apartment. A garden is planted. Their mother leaves them to return to work, and shortly thereafter decides to remain at home. They navigate a staircase. A grandmother dies. They have a birthday party. In between, they sleep and dream and play and think. They watch, intently. They see their parents down to the last detail; they examine every nuance, every word, every movement. They understand who their parents are, at a fundamental level. This, to me, is well-observed by Glück and particularly true to life—at this age, children see you far better than you see yourself, and sometimes the clearest image of yourself you’ll ever get is when they begin to reflect it back at you.

It’s hard to imagine a story as slight and specific as “Marigold and Rose” finding much of an audience beyond Glück completists, though it would be a perfect baby shower gift for literary-minded parents-to-be. Parents and grandparents often make the mistake of thinking their babies are fascinating to everyone and no doubt some will see this book as just that kind of starry-eyed misperception. But as someone who has experienced what Glück depicts firsthand, it was nice to have a way to travel back to that time, and relive that feeling of newness and wonder.