Advertisement

A 'gonzo journalist of the occult' hunts for the ghosts in our machines

ResumeIn a 1960s “Twilight Zone" episode a boy's grandmother gives him a toy telephone as a birthday gift. After she dies, she uses it to speak to him from beyond the grave. Then there’s the '80s movie “Poltergeist” that showed spirits entering a family’s home through their television set.

For a young Peter Bebergal, stories like this sparked a lifelong interest in the idea of haunted communication devices.

The Cambridge author has been studying religion and the supernatural for over 20 years. Recently he’s been delving into how some of us have used technology to connect with ghosts — and what he discovered is uncanny.

People have long attempted to reach spirits through seances and Ouija boards, especially on Halloween, a time when it’s believed the ethereal veil between the living and the dead is especially thin. But Bebergal said throughout history people have also tapped into all kinds of new technologies hoping to connect with the other side.

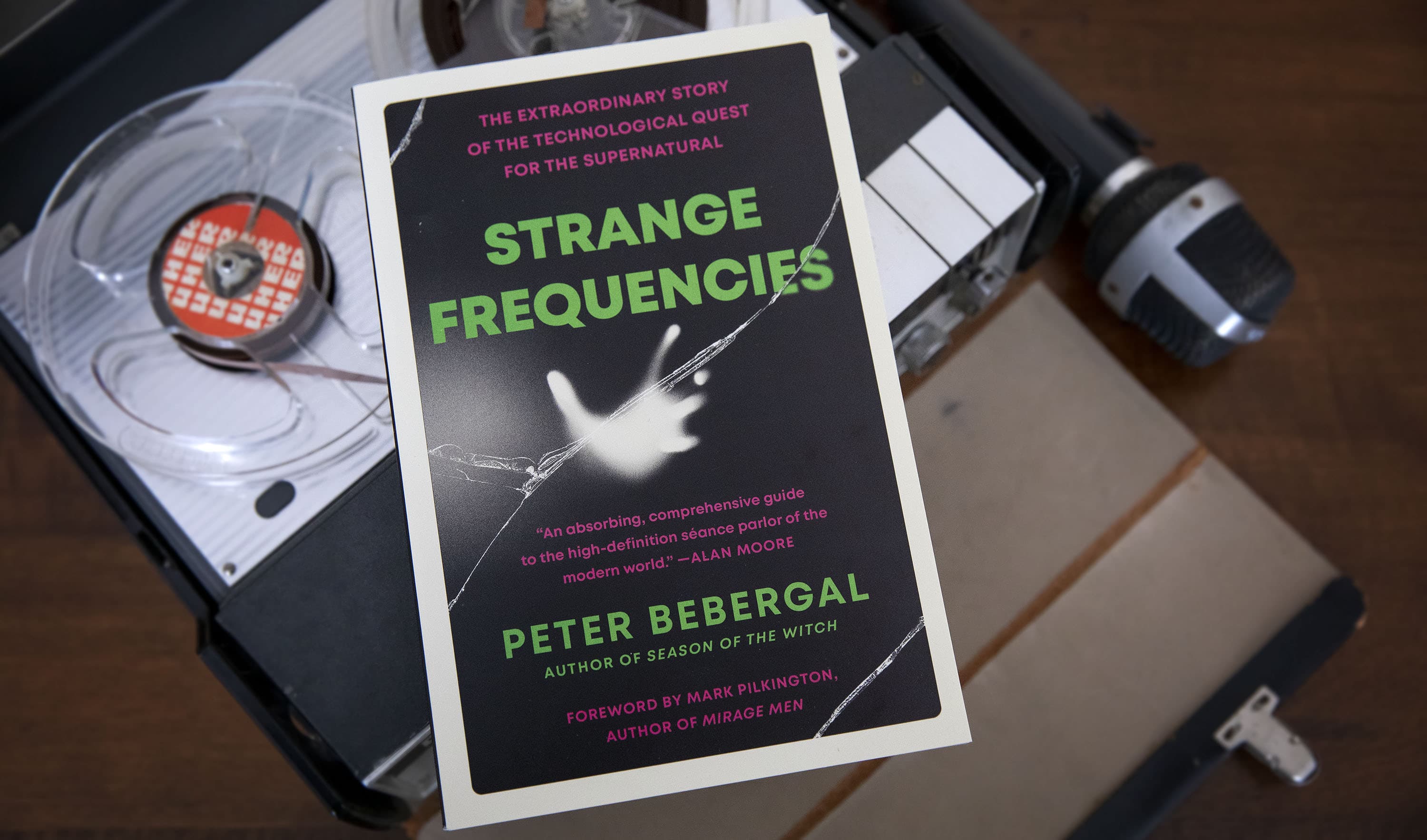

Their efforts are the subject of his latest deep-dive book, now out in paperback, titled “Strange Frequencies.”

“My work is not about trying to prove them wrong or make them look silly, I just want to be able to show how culture, for as long as we have been human, has attempted through ritual — and in this case, technology — to interact with some form of the spirit world,” Bebergal said.

He points to the 1800s when what's known as the spiritualism movement went viral. “They would say spirits are with us all the time — they're sort of just waiting for us to come up with the right technologies to be able to reveal themselves to us.”

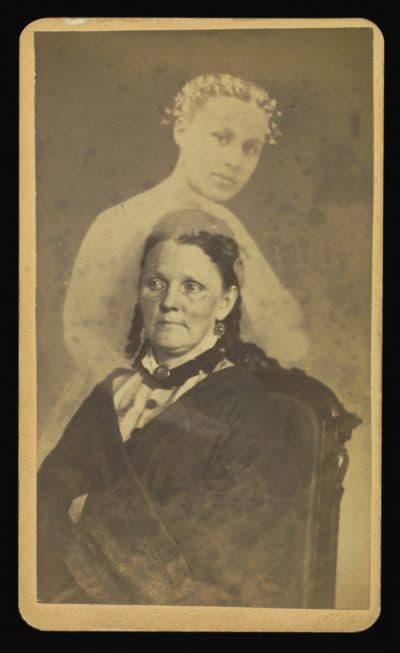

Enter the camera. Its invention gave rise to “spirit photography.” Victorian-era practitioners claimed they could capture images of people's dead relatives. One of the most famous examples is a portrait of Mary Todd Lincoln, taken by Boston spirit photographer William Mumler, with the supposed specter of President Lincoln by her side.

The advent of electromagnetic waves spawned the search for sounds from the spirit realm. In the mid-20th century, after radio broadcasting spread across the globe, researchers found ways to scan its frequencies for paranormal messages. They called this “electronic voice phenomena,” or EVP.

“If you're dead, you don't have a body — you're just a disembodied consciousness, you don't have vocal cords,” Bebergal said, explaining their rationale. “So you need something like radio waves to be able to align your dead consciousness with in order for people on the other side to be able to hear you.”

Bebergal, who sees himself as something of a “gonzo journalist of the occult,” decided to try this out for himself. After reading about EVP in historical books and mainstream magazines, he pulled up instructions on the internet to create his own ghost-detecting radio. It rolls through frequencies without stopping, he explained, “so what you get are these blips of voices or songs throughout the stations, and it could be sort of like an electronic Ouija board.”

Lucky for us, Bebergal even recorded that experiment. When he played it back for me, he asked if I, too, heard a voice utter the word “skeleton.” Did I? Maybe I did...

Bebergal said the power of suggestion, desire and mourning play big roles in the search for spirits through technology. These days, there are plenty of apps to sate our curiosity about who or what might be reachable. Bebergal pulled one up called the Ghost Voice Box Communicator.

“Should we ask if there are spirits in the room?” he said, then egged them on for a response. A menacing voice answered through staticky sound effects. We think it said, “I'm desperate.”

While the apps are creepy — and, yes, pretty cheesy — Bebergal said the bereaved are usually seeking comfort when they try to contact those who’ve been lost. An “electronic voice phenomena” researcher encouraged him to make his exploration more personal by trying to record audio of his father who had recently passed away.

“And, as reasonably skeptical as I am, the last thing I wanted to do was hear the voice of my dead father coming through a tape recorder,” Bebergal admitted with a laugh. “But in the service of the subject, so that I could better write about it, I decided I would give it a shot.”

So, Bebergal dug out his father's old reel-to-reel tape machine from storage, set it up, and said, “Dad, if you're here, I'm going to leave the tape recorder on. I'm going to leave if you want to give me a message — and I'll come back — and I'll listen.”

Bebergal went out to get a cup of coffee, and tried to remain neutral.

“I do think that even then there was a part of me that was hoping for something,” he remembered. “I came home. I turned off the recorder. I re-wound it. And I listened."

And there was nothing.

Then he amplified the recording through his computer, hoping to catch something he might have missed.

“Still nothing,” Bebergal said.

In life, his father was a real skeptic. “His spirit might have said he's not playing these games with me," Bebergal said. "In any case, the tape was completely blank."

But, as he was about to pack up the recorder, Bebergal said he noticed another old reel. With his wife and son sitting nearby, he threaded that tape through his dad's beloved machine and pressed play.

A young, female voice counted the numbers one and two. Then a piano chimed in and the woman stopped and started her way into a wobbly but endearing rendition of "Tell Me More," a song from the 1950s.

It struck Bebergal that the voice on that vintage reel was his mother's. “When she was probably in her early 20s,” Bebergal explained, “singing into this very tape recorder.”

From across the room his son, Sam, wondered who they were listening to. Bebergal replied, “Oh my gosh, that's your grandmother who you never got to meet." She had died a couple of years before Sam was born.

And suddenly Bebergal had a realization about his experiment: “That it did work. I was, in this moment, hearing the voice of my mother who had passed away. And my son — who had never heard her voice before — was hearing it for the first time," he recalled. "And it was just absolutely chilling.”

While he didn’t actually commune with his dead parents, Bebergal said this serendipitous encounter opened him up to the mystery of things. He thinks that’s what he really wanted. And now he’ll treasure his father's once forgotten machine that brought his mother's voice back to life.