Advertisement

In Boston, connecting Black outdoor lovers with nature

On a chilly fall morning, along the winding path of the Back Bay Fens, Kaitlin Smith searches through a carpet of red and orange leaves for something special. It only takes a moment before she finds what she's looking for.

"Here's one!" Smith opens her palm to reveal a petite, pinstriped acorn. "Those lines indicate that this acorn probably came from a pin oak," she elaborates. "Most people don't necessarily like to process these since they're so tiny." Processing acorns is an intensive process that includes drying the acorns, cracking them open and removing the tannins from the nut meat through cold or hot leaching.

"It's a lot of work, which is why many look for bigger acorns." Smith bends down again and straightens, this time with a fat and round one. "Acorn processing is a major part of many Indigenous communities where there are oak trees. It's fascinating the things you can use acorns for."

Smith doesn't just find, assess and collect acorns for fun. She recently led a local group on an adventure along the Fens, teaching participants about acorns while connecting the process to author Octavia Butler's "Earthseed" series. She's one of several local volunteer leaders for Outdoor Afro, a national not-for-profit organization that connects Black people with nature and each other.

As one of the local leaders, Smith finds it exciting to share her love of foraging, bioregional herbalism and nature with others. "We're able to provide a welcoming environment for people of all skill levels in the area and I just think that's so incredible." Her passion for teaching others is apparent as she pulls out a jar filled with acorns she dried last year. Once the acorns are processed, Smith can turn them into flour and other edible food products.

"It is essential for people of color and Black people to have safe communities that center nature," says Outdoor Afro founder Rue Mapp. She spent her adolescence frolicking and working on her father's 14-acre ranch in California, where she was intimately connected with the outdoors. "But I found that when I got older and I sought out groups to participate in outdoor recreation activities... I didn't see enough people who look like me." This lack of representation is what led Mapp to start Outdoor Afro in 2009.

The "nature" gap is a term used to describe experiences like Mapp's. The gap is a marked disparity in the participation and representation of people of color in outdoor activities like fishing, hunting and hiking. Data from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service show that white people represent an overwhelming majority of those who take part in fishing, hunting and other wildlife-associated recreational activities.

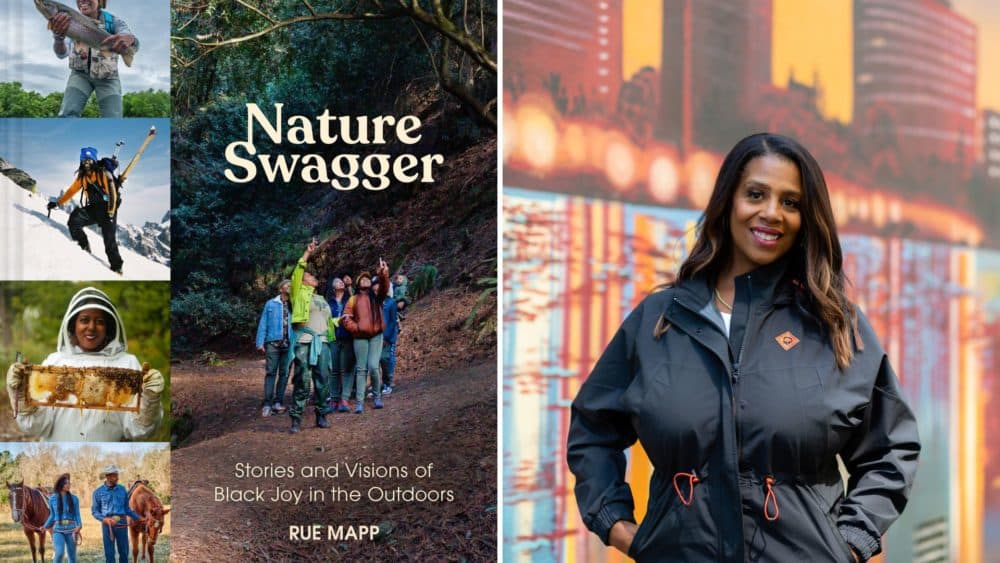

The glossy pages and ads of outdoor magazines and companies featuring mostly white models reinforce the perception that people of color don't "hike, camp or whatever the misconception or stereotype may be," says Mapp. "But people of color have always been immersed in the outdoors, often as stewards and protectors of the land they're inhabiting." Her recently released book, "Nature Swagger," reinvents these misconceptions by placing Black people and their stories front and center in the outdoor experience.

"Racism and discrimination have created barriers for Black people looking to get outdoors," Mapp points out. A 2015 study published by the Travel and Tourism Research Association traces how racist outdoor policies have created and exasperated the "adventure gap." "Indigenous people were forced off of their land. Black and people of color were straight up not allowed to access certain parks or certain areas," Mapp says. "Nature was marketed as an 'American' past time but who fits into the narrative of what an American is?"

Beyond racist policies and fear of discrimination, a sense of unease also keeps Black and people of color from taking advantage of the outdoors. Kaitlin Smith is no stranger to this — she recalls an instance when a white man confronted and questioned her, simply for being in the forest. "He said to me, 'What're you doing here?' and other things like, 'You're not allowed to pick anything' and other invasive comments. He didn't actually work for the park or the state or anything like that. It was just a random person who felt compelled to tell me what I ought to be doing and where I belonged."

Luckily, Smith was with a group so she felt less apprehension than she would have if she'd been alone. "This is precisely why groups like Outdoor Afro are so important," she says. "That instance illuminated how powerful it can be to have a group of people to venture out into the forest with so that you can feel a greater sense of security and build community as well."

As of this year, Outdoor Afro has over 60,000 network participants and 32 states with local networks. Volunteer leaders, like Smith, go through a training process before they begin organizing meetups and leading groups. In Massachusetts, activities include outings like Smith's foraging walks to more intense excursions like rock climbing at Pawtuckaway State Park in New Hampshire.

"Our networks are kind of like a system of on ramps and off ramps, like you can get in and get into the slow lane and do that neighborhood walk or you could get into the fast lane and you might find yourself on, you know, a trek to Kilimanjaro," Mapp says.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the process for drying acorns. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on November 10, 2022.