Advertisement

There's a hole in the state's climate efforts: elementary education

Most teachers in the U.S. agree that climate change should be taught in schools, with some advocates saying it should start in lower grades. But in Massachusetts, climate change topics are not part of the state's elementary learning standards, leaving schools on their own to find extra resources.

In public schools, elementary students are expected to learn about topics like the weather and energy — but not necessarily how to connect that information to the climate crisis that will inevitably shape their future.

In fact, climate change topics are not included in much of Massachusetts’ curriculum materials or learning standards, according to a recent report co-authored by the nonprofit North American Association for Environmental Education.

The study analyzed publicly available documents from boards of education and state education departments across the U.S. and ranked Massachusetts in the lowest tier — along with most of the country— with “very low” inclusion of climate change-related content in state requirements.

The research does not take into account efforts by individual districts or teachers to go above and beyond what states ask, and some schools are doing just that.

Instilling ‘a sense of agency’ at a young age

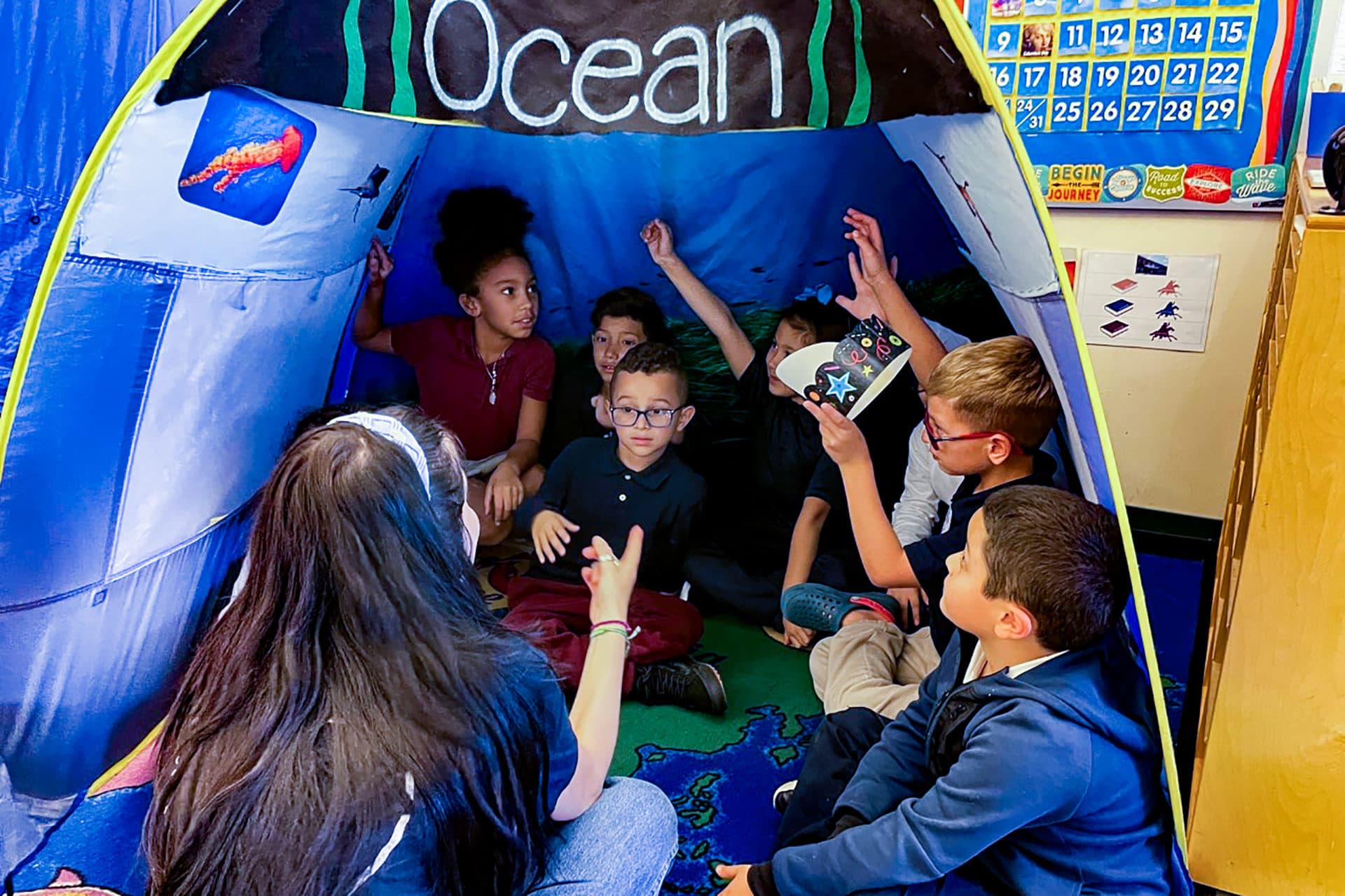

One recent fall morning at Paul Revere Elementary in Revere, a chorus of first graders are on their feet, ribbitting like spadefoot toads over the sounds of honking horns and highway traffic.

Then the students begin experimenting with building sound barriers to protect the threatened species, layering different materials and testing how well their walls block noise using decibel meters.

The interactive lesson is led by Change is Simple, an environmental education nonprofit in Beverly that partners with elementary schools to provide climate and sustainability education.

The nonprofit was founded 11 years ago with the idea that climate education needs to be introduced early, when kids’ minds are open to new ideas.

“It's really a unique time period to educate them about environmental science and climate change so that this becomes something that they value and are committed to over a lifetime,” says Sara Ewell, a Northeastern University professor and a third-party researcher studying the effectiveness of the nonprofit’s work in elementary grades.

She says giving young kids this knowledge earlier will make a difference in a future generation of environmental stewards.

“While this is a global problem, it can also be a problem where they can take steps to make changes within their own life,” says Ewell.

Co-founder Patrick Belmonte says Change is Simple teaches lessons on everything from biodiversity to renewable energy with an approach that aims to give students a sense of agency.

Advertisement

“We just took a really different approach from the start, which was all about hope and empowerment with students,” said Belmonte.

The work is especially relevant in coastal communities like Revere that are disproportionately exposed to environmental risks, such as sea-level rise and air pollution.

Bringing climate into the classroom

Dorrie Shupe, a second grade teacher at Paul Revere Elementary, says her students love the hands-on lessons from Change is Simple.

“They're learning other things that maybe I don't necessarily know how to teach them at this point,” says Shupe. “Or I could teach them, it just takes me a lot more work.”

Elementary school teachers are often responsible for teaching across all subjects in their grade, juggling dozens of learning standards from the state. The standards outline what students are expected to know each year, and individual districts, schools and teachers are responsible for meeting those expectations.

Currently, state guidance specifically notes in a third grade standard on weather and a fifth grade standard on natural resources that an understanding of climate change is not expected.

“Right now, it's just sort of like we have to teach about the world, but we don't have to teach about what happens if we don't take care of it,” says Shupe.

Through grants and active fundraising, Paul Revere Elementary has been able to bring in Change is Simple for the past six years. This year, the partnership expanded to all five elementary schools in the district.

But not all schools have the time or resources. Some teachers have called for more support at the state level to provide climate education to all students.

“We want to make sure that everybody, every public school student has a chance to be exposed to this,” says Justin Brown, a fourth grader teacher in Brookline who organizes with other teachers for climate justice. “That's why bills and standards are so important.”

Brown wants more climate resources and professional development for teachers, as well as state legislation that would create a climate change curriculum.

“Educators need to know the content and they need to know the pedagogy. Like what's the best way to teach this and how to do it in a way that's developmentally appropriate,” said Brown.

A pair of bills in the Massachusetts House and Senate that would have implemented statewide climate education failed this past session. Advocates plan to submit a new draft in the next cycle.

An emphasis on climate justice

Some youth activists are taking the lead in a more comprehensive approach to climate education, and schools are welcoming them to get younger kids engaged.

Spring Forward is a student-run organization of high schoolers across the state that brings climate education to schools and summer camps. The group, like many climate education advocates, believe the topic goes beyond science and touches subjects like English language arts, social studies, math, and more.

“We didn't have this education in middle and elementary school,” said Alice Fan, a senior at Phillips Academy in Andover and one of the group’s leaders. “And we really felt that every person should be learning about climate change because it's so relevant to our future.”

Fan leads weekly climate lessons with third to fifth grade students from an after school program in neighboring Lawrence.

“If you look at an environmental justice map of Massachusetts, you can see a very clear line between Andover and Lawrence,” says Fan.

Lawrence is home to mostly immigrant and low-income families, and a decades-long effort to clean up pollution left over from abandoned industrial sites. Fan says her access to climate education is a privilege, and hopes she can use it to make a difference.

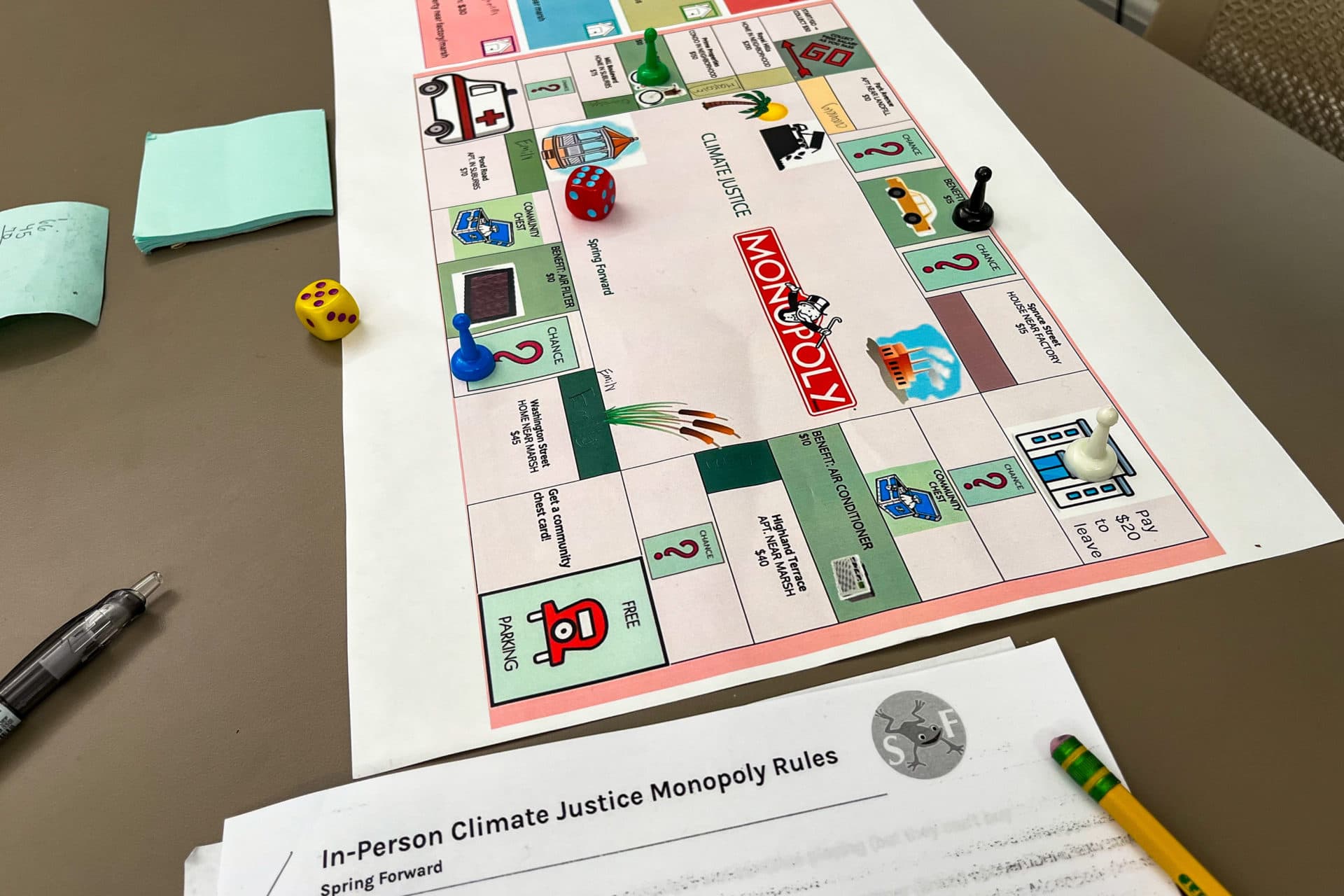

For a recent Wednesday evening, she’s come prepared with a crowd favorite: Climate Justice Monopoly.

The game is designed to be unfair, she advises at the start. Players begin with unequal pots of money and move their pieces across a reimagined Monopoly board, with color-coded neighborhoods based on environmental risks. The players pay fees for living near pollution or in housing that’s vulnerable to extreme weather.

“If you live in the brown area, the factory pollution has induced an asthma attack for your family member,” Fan reads. “Pay hospital costs of seven dollars.” A student gasps as she checks her balance.

Spring Forward created an entire climate curriculum with lessons like this one, teaching kids how the climate crisis overlaps with race, gender and economic disparities. This includes more complex topics like redlining, social inequality and how students can fight for institutional change.

Fan says the message rings differently coming from a fellow student, delivered in a casual setting with no grades attached.

The lesson pauses for a Taylor Swift dance break and winds down with a discussion on how climate change impacts certain communities more than others.

In all, Spring Forward volunteers have reached about 2,000 students since it began two years ago. Fan says it’s a small operation doing meaningful work for her generation.

“We're all in this together, as young people,” says Fan.

She graduates next spring and hopes to find someone to take her place teaching after school.

Barring a change at the state level, schools will continue leaning on volunteers like Fan — or the individual efforts of dedicated teachers and nonprofits — to teach elementary students about climate change. Until then, climate educators of all forms will continue in their work to equip the next generation for the consequences of the climate crisis.

This segment aired on November 18, 2022.